Marc Johnson

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

David Pettyjohn: Good evening everyone. Thank you so much for joining us for tonight's Connected Conversation, a program of the Idaho Humanities Council. For those of you not familiar with our work, I encourage you to visit our website, Idaho humanities.org. I'm David Pettyjohn, I'm the IHC executive director, and I'm filling in for our usual host, Doug Exton. And I'm coming to you live from our ginger house, which is home of IBC World Headquarters, and we are located a few blocks to the east of the Idaho State Capitol, a building that tonight's speaker knows very well.

So before I introduce tonight's speaker, I want to remind you that you may submit questions using the Q and A feature at the bottom of your screen or the chat feature also at the bottom of your screen. Now joining us this evening is a very dear friend of the council, Marc Johnson. Marc is a former chair of the IHC board and also a former chair of the Board of Directors of the Federation of State Humanities Council.

Marc served as chief of staff for Governor Cecil Andrus, and his most recent book is Political Hellraiser The Life and Times of Senator Burton Kay Wheeler of Montana and his writing on politics and history have appeared in Montana, The Magazine of Western History, The Blue Review, the California Journal of Politics and Policy, The New York Times, and many Idaho and regional newspapers.

His next book, "Tuesday Night Massacre Four Senate Elections and the radicalization of the Republican Party", is the story of how independent expenditure campaigns began and how those campaigns up and politics, beginning with Senate contests in 1980. It is due to be published next year. Now, he joins us tonight to discuss one of Idaho's most interesting politicians and, as the title said, perhaps controversial politicians.

Senator Glen Taylor, Mark, welcome. And it is an honor to have you with us this evening. So I will turn this over to you.

Marc Johnson: Thank you. David. Thank you so much for the nice introduction. I'm, zooming in from, my library on the north coast of Oregon in, Manzanita near Manzanita. And it's a pleasure to be back with my old, pals at the council tonight. My way of starting. I'll just say that every state, has its political characters.

Some states more than others. Arguably, Idaho has had more than its fair share of political characters controversial, sometimes flamboyant, outrageous, sometimes not very bright, even occasionally the, the out and out crook in the group. But, the guy I want to talk about tonight, Glen Taylor. See if I can share the screen and get started here.

Early on in his political career, when Taylor, who was a many time candidate but only one time elected, was deemed to be a bit flaky, a little unserious, certainly not senatorial. Later, the allegations against Glen Taylor became even nastier. He was, described as a communist, a socialist, a dupe of the Soviets. Hence I call him a controversial politician.

Arguably the most controversial in Idaho's history, I think I could say without, fear of contradiction. He was the most liberal politician ever elected to a major office in Idaho. Someone asked me sometime back when I was giving a talk about Idaho politics in the 1950s. If I thought Glen Taylor could be elected to anything in Idaho today.

And I said, well, maybe the Blaine County Commission or the Ketchum City Council. But he might even be, have been too liberal for that group. But a good deal of the labeling of Glen Taylor, in my opinion, was just wrong. He was a supreme example of the self-made man. That's his biographer, Ross Peterson, a really great historian who taught many years at Utah State University, has written, Taylor's career was a vindication of the ancient notion that ideals have virtue and that, can only and that ideals can only be sacrificed at a loss of honor.

So Glen Taylor was, an honorable guy, a guy with, strong convictions that he held throughout his entire life. Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown has written a book about a number of United States senators who sat at the desk that he now occupies in the Senate--desk 88. That's the title of the book. There's a chapter in, Senator Brown's book devoted, to Glen Taylor and Sherrod Brown says we could use more guys like Glen Taylor, today.

So let me give you a little background about this guy. He was born in Portland, Oregon, actually in 1904, the 12th of 13 children. His father was an itinerant, Disciples of Christ preacher, a real hellfire and brimstone, preacher. According to Glenn, his father's name was Pleasant John Taylor. That was his real name, Pleasant John. The family, needless to say, had trouble making ends meet with 13 children on the, meager income of an itinerant preacher.

So, right about the time of the First World War, the family relocated to Kooskia, in North Idaho. And it was a very tough, life trying to eke out an existence on a on a rough farm. Glenn's father actually became ill with the, Spanish flu, the influenza, in 1918. And he left school because he needed to go, to work.

To help support the family. So he probably wound up with about a sixth grade education, work through a variety of odd jobs from, running a projector and a theater. To, you know, working in the woods. Anything he could do, to make a living. One of his brothers was living in California. This would have been in the early 1920s.

And he invited his, brother Glenn to come on down to California so that the, the two brothers could develop a a vaudeville group, a traveling music, and play, putting on little skits and performance as the Taylor Players. They traveled all over the western United States. The Taylor Players. And during an appearance in Great Falls, Montana, Glenn met his future wife, Nora.

They created their own band. The Glendora Ranch gang. Glen and or one in Dora Ranch gang finally settled down. This is a beginning now of really tough times in the American West, even before the Great Depression. Beginning with the sort of marking the beginning of the stock market crash in 1929. Things in the West had been really rough in the farm economy.

A depression had existed in, the farm belt. During much of the 1920s. So this was a very much a hand in mouth existence, for these, folks who were trying to eke out a life, as, performers. They finally settled in Pocatello and got a regular radio show on KSEE radio. They did a daily, afternoon radio show.

And then at night, would travel around eastern Idaho, performing at grange halls and county fairs and different, venues. Good old mountain music became their theme song. And, their son, A-Rod, was born in this period. A-Rod is Dora spelled backwards. Their oldest son, about the same time as Glenn, is trying to eke out this existence as a as a singer and a performer.

He starts to take an increased interest in politics, and he read a book by this guy, King Gillette, the inventor of the safety razor. Gillette was a self-described socialist, utopian socialist. His economic ideas were, to say the least, somewhat novel. One of his great ideas, the People's Corporation, was that every person in the United States would receive one share of stock in a corporation that would own all the other corporations in the country.

Taylor would later say that up to that moment when he read King Gillette's book, he had always accepted the American economic system on its face, the idea that there would be, hunger in the midst of plenty, that, guys like him were destined to lead a life of, struggle and poverty. But he began to think differently about, economics and politics after reading, the Gillette book.

And he saw that politics could be a path to societal change. He told Dora finally in 1938 that he was going to run for Congress. And again, they barely had, the rent money. Little name recognition. No, absolutely no political experience up to this point. But when Taylor ran for an open seat in the second, Congressional District in Idaho, he ran very much as an outsider, saying that he wasn't really sure that he was a full on Democrat, but, that his, father was a Democrat, and he'd, decided that maybe that's where he should make his stand.

He supported farmers. He said he was a full on supporter of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. And he was a supporter of organized labor. He lost, finished fourth, actually, in, a four way race. But he did have a gimmick. This article is from a later campaign, but it's it was, illustrative of, the kind of showman that Glen Taylor was.

He decided he would ride around the district on horseback. And this is from one of his Senate races later, from Coeur d'Alene to Granville, from Wizard to Boise, on to Rupert, Pocatello. And he would ride around the state, drumming up any attention he could get, often carrying his, guitar or, banjo with him. So he could play a song before launching into, his political stump speech.

The great Idaho, author and novelist Vardis Fisher, once said, I listen to Glenn speak every time I get a chance. Not because he ever says anything, but because he says nothing superbly. Fisher, should be said was a bit of a crank. But there's little doubt that this polished musical performer, Glen Taylor, was becoming also a polished stump speaker.

On another occasion of art, as Fisher said, there were two really great political speakers in the country Franklin Roosevelt and Glen Taylor. Also during this period, Glenn became concerned, as some of us do, about, his hair loss. And he decided that one thing he had to do was, counteract that, increasing baldness. And he decided that he would make his own hairpiece.

He fashioned a hairpiece out of a piece of aluminum. Somehow attached human or some kind of hair to it and fashioned, what would be eventually become the Taylor topper. His business after his political life. He made his own toupee, thinking it would make him look younger and have more appeal on the campaign trail.

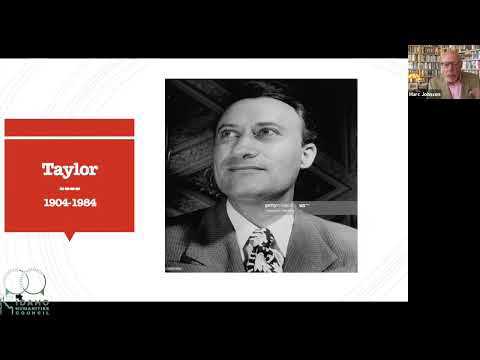

So he ran for Congress in 1938, finished fourth in Democratic primary, runs again in 1940 for the Senate. Runs again in 1942, and loses again for the Senate. And finally in 1944. Audaciously, he challenges the Democratic incumbent Senator Dewhurst Clark, and wins a U.S. Senate election from Idaho. So here's Glen Taylor about this time, 1944, taking on the Clark, what he called always called the Clark Dynasty.

Worse, Clark had been elected to a as a congressman from eastern Idaho and then a senator in 1938. His two uncles were governors of Idaho. His cousin was Bethine Church later married to Frank Church. Clark was a very conservative Democrat. One thing you have to understand about Idaho politics in this period was that both parties had, factions.

There was a conservative Democratic faction, a more liberal Democratic faction. Same with Republicans. Worse, Clark was very much in the conservative Democratic faction, and Glen Taylor was very much in the liberal Democratic faction. He beat Clark in the primary in 1944 by a grand total of 216 votes, and then goes on, to win the general election. In a Democratic romp, you don't often see a headline like this in Idaho, but in 1944, it was an extremely good year, for Democrats in Idaho.

On the strength of a near Democratic sweep, Taylor won the Senate seat, beating the incumbent Republican governor, and arguably takes office in the Senate as the most liberal member of the United States Senate. Going to Washington, DC. Taylor again, you know, very limited, financial means finds that, because of the housing shortage and the District of Columbia, that there literally is no place for him and Dora and their young family to rent an apartment or to rent a house.

And, he is kind of desperate to find a place to live, not being able to afford living in a hotel. You want something more affordable? So what does he do? He takes his banjo to this capitol, steps with two of his children and Dora. And, creates a little press event here on the Capitol. Steps. Sings a song that he, had written himself or give me a home under the Capitol dome, and, was able to secure, accommodations for his family as a brand new United States senator.

By the way, he also worked, in this period and. Right after this period on housing legislation, realizing that if he was a United States senator, was having trouble with housing. What about all the, GIs that would be returning from World War Two? What were they going to do for housing? And he put, a lot of effort into finding solutions for that problem.

He also could be a brawler. As this headline indicates, this is from 1946. Taylor gets into a, fisticuffs event. Just outside of the Boise Hotel. Right after the election in 1946. So the pendulum swings back. Republicans win a bunch more seats. Back in Idaho in 1946. Taylor is still in the Senate, of course, but he takes umbrage at being, when it's suggested that maybe he has been a drag on the entire Democratic ticket and he takes a swing at, one of the top Republicans in the state, Ray McCaig.

But his real fights were confined to the Senate floor, including a very celebrated battle over whether the Senate would seat this guy, Theodore Bilbo, a Democratic senator from Mississippi. And in the 1940s, a virulent racist, even by his own, his own admission, Bilbo was a racist. He said some absolutely awful things during his reelection campaign in 1946, including that, African-American voters in Mississippi should be denied the vote entirely until, transportation could be arranged to take them back to Africa.

Inquiry is, conducted into Bilbo's. Bilbo's efforts to intimidate Black voters in Mississippi. Two different Senate committees take up this question. And both find, ample reason to believe that, yes, he had gone out of his way to intimidate voters, to threaten, Black voters in his home state of Mississippi. And the issue comes to the Senate floor finally, late in 1947.

As the Senate historian has written, the Idaho senator pointed out that a precedent existed for asking the senator to stand aside when a committee had already found evidence of his corruption. The Senate, however, voted 38 to 22 to table Taylor's resolution, demanding that Bilbo, essentially not take his seat in the Senate. Southern senators began a brief filibuster to block efforts to elect the Senate leadership and organized the new Congress.

The impact, impasse was finally broken when an agreement was reached that Bilbo would basically not participate in any activities in the Senate, which was easy for him to do because he was suffering from cancer and undergoing cancer treatment. And he basically went back to Mississippi, never to return to Washington, DC. And died in August of 1947, with the Senate taking no further action on his case.

But it's a testament to Glen Taylor's, courage and his commitment to civil rights that he, not alone, but alone among Democrats at that point was willing to speak up on behalf of African American voters who had been systematically disenfranchized by Bilbo first, when he was governor and later when he was a United States senator.

During this period also. Taylor becomes increasingly disenchanted with the Truman administration. He disagrees with Truman's foreign policy. Thinks Truman is too bellicose with the Soviet Union, that there should be some kind of opportunity for a, modus vivendi if you will, with the Soviets after World War two. He's very concerned that the Democratic Party is not being aggressive enough in advancing a civil rights agenda.

And at the request of, Henry Wallace, who had been vice president under Franklin Roosevelt and earlier, Secretary of Agriculture and then Secretary of Commerce, he joins with Wallace to form a Progressive Party ticket and run for president and vice president in 1948. So Taylor basically bolts, the Democratic Party as part of a campaign, his efforts to prevent the seating of Senator Bilbo.

African-American voters across the country really rally to the Progressive Party. They think the Progressive Party is really, serious about civil rights. Not sure that the Democrats and Republicans are. And, of course, the Democratic Party in this, period is still in many ways dominated by southern segregate US senators. So Taylor goes to Birmingham, Alabama, to speak to a, gathering of African-American youth leaders.

And he attempts to enter the meeting through a door that was marked, for Negroes only. He was arrested and, put in jail has quite a run in with the infamous police commissioner in Birmingham, Bull Connor, who would later have run ins with many civil rights leaders. Taylor is, fined and spent, the night in jail.

He eventually, appeals, the contempt citation and takes the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, hoping that the court will hear the case on the grounds of the constitutionality or the unconstitutional nature of the segregationist. Practice that he was trying to highlight in, his appearance in Birmingham. The Supreme Court fails to take up the case in 1950.

But again, a testament to the guy's commitment to civil rights and a gutsy position for a Westerner. Then, as now, Idaho. Not exactly known as, on the vanguard of, civil rights. But he certainly staked out a position to that effect. The progressives run a very, spirited campaign in 1948. And in many ways, the Democratic Party eventually adopts many of the policy platforms.

Platform policies of, the Progressive Party in 1948. They don't win any states, and they run very poorly in Idaho, in part because of allegations that the party was under the influence of, communist sympathizers or even Russian influence, echoes of a current, debate, perhaps, there was some good reason for that. Henry Wallace refused to, condemn, communist support for the progressives and, that did not help the Progressive Party cause, in any way.

Harry Truman, of course, wins, the election. And one of the great political comebacks in American political history. This is also the campaign that Strom Thurmond runs as the Dixiecrat candidate and wins several states in the Deep South in 1948, but Truman one wins the popular vote and the Electoral College and is elected in 1948. Taylor at this point begins to ease his way back into the Democratic Party, apparently without too much difficulty, and begins to get again to work in the Senate on his quite liberal agenda.

He is, completely in favor of a national health insurance program that President Truman had, advocated in this period. He supports the, proposed, Columbia Valley Authority, which would, have been modeled on the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Pacific Northwest, basin wide planning and development of the Columbia Valley in the same way that the Tennessee Valley had been developed in Mississippi and Tennessee and elsewhere in the southeast.

And Taylor continued to advocate on behalf of the, Columbia Valley Authority even after it became, very much out of favor, even with, other Democrats, Idaho water users. Again, echoes of current day politics. Completely rejected the idea of a Columbia Valley authority for fear that it would, present a threat to Idaho's water.

And also during this period, Taylor is the first member of the United States Senate to clash with Joe McCarthy. Here's McCarthy with Roy Cohn, his attorney, on the Senate government, investigations Permanent Committee investigating and investigation subcommittee, Roy Cohn, later Donald Trump's personal attorney. And in a speech in 1950. Early in 1950, Taylor on the Senate floor, accuses McCarthy of being a demagogue, saying that he has no proof of the Communist influence in the State Department.

That McCarthy is alleging, and he really becomes the first member of the United States Senate to aggressively speak out against McCarthy and his efforts. So Taylor didn't exactly, repudiate his Progressive Party, run. But he knew that if he had any chance to get reelected in Idaho in 1950, he would have to slide back into the Democratic Party.

He would say later in his life that running with Henry Wallace on the Progressive Party ticket in 1948 was the proudest thing in his political career. And if he had it to do all over again, he would have done it just the same way as he had. So the 1950 reelection and the Democratic primary in Idaho sets up a rematch between Taylor and Wirth.

Clark, Clark coming at Taylor from the political right. Taylor defending the allegations that, you know, he's been cavorting with communists and socialists, too soft on, the Soviets, etc.. And this time, the the tables turned worse. Clark ekes out a narrow, victory in the, in the Democratic primary. And then goes on to lose the general election to this guy, Herman Welker.

Welker was an attorney from Pat. Former state legislator runs on the Republican ticket in 1950. And, timing being what it is in politics, he arrives on the scene just in time to become, Joe McCarthy's best friend in the Senate. And, for the remainder of his life, a real nemesis, to Glen Taylor. But even with Walker's victory in 1950, Taylor is far from done.

Running for public office.

In 1954, he runs again for the Senate against, the incumbent Republican, Senator Dwarf Ishak. And this is from a column by the Statesman's political editor at the time, John Corlett. Correlate says Taylor is running on his record for the very first time, and he has no real record except for his socialism that he learned from that book, back in 19, in the 1940s.

He loses the Taylor, loses this election, to Henry Dwyer. Shock. Who, with all due respect to the senator, had a rather, less than distinguished and a career in the Senate. The lasting memorial to Henry Door, of course, is the big dam in Clearwater County. Door. Shack. Dam. The shack did have a, a bit of a role in the Senate.

McCarthy era, to the extent that he served on the, special committee in the Senate that investigated McCarthy's allegations against the U.S. Army, the allegations that eventually resulted in the Senate censuring McCarthy in 1954. Although Dewhurst, Jack and Welker remained absolute, confidants and supporters of McCarthy even after his censure. So moving along to 1956, Taylor and comes up against his last campaign against a 32 year old Boise attorney by the name of Frank Church.

Church and Taylor face off in a, pretty tough Democratic primary election, which Taylor wins by 200 votes. I'm sorry, which church wins by 200 votes? It's a testament, however, to Taylor's, continuing support in the Democratic Party. Now, remember, this guy's been running, almost nonstop since 1938, and he still comes remarkably close to winning yet another Democratic primary.

He demands a recount, believing that the election has been stolen from him, by the clerk machine because of Frank Church's connection to the Clark family through his marriage to Beth in. He demands a recount, which, church, refuses to countenance. Countenance. There was no, prescription under Idaho law at that time. To have a recount in a federal election.

And, so Taylor takes it on up on himself to go door to door in Elmore County. Mountain home. Believing that this is where the election has been stolen. Because, some of church's top campaign advisors hailed from Mountain Home. He is not able to prove that the election is stolen for him, but he absolutely goes to his grave believing that, in fact, it has been stolen from him.

Church goes on to win the general election against Herman Welker that fall. In a landslide. Welker is out of sorts with his own Republican Party by this point, barely survives his own contested Republican primary. And it was a big year for, for the GOP nationally with, Dwight Eisenhower second term election. But even against that Republican onslaught, Frank Church wins the Senate election in 1956 with 56% of the vote.

He carried 40 of Idaho's 44 counties. But Taylor, was still not willing to give up. After the primary and the 200 vote loss to Frank Church. He mounts a write in campaign of his own to, challenge Church and Walker in the general election and gets more than 10,000 votes in that. Right. And, he would later admit, and political observers were astounded that he seemed to have a lot of money to run this campaign, this write in campaign.

He later admits that, some of Walker's Republican friends had provided the financing for him to, run in the general election on a write in basis, believing that maybe Taylor could take enough votes from Frank Church, that Welker could somehow sneak behind church wins. Nonetheless, he goes on to a distinguished four term, career in the U.S. Senate.

Taylor does, have one, other lasting legacy in Idaho. That is the, the recount law that, was prompted by his extremely close election in 1956, also prompts a great story by, Richard Neuberger, who was a very prominent journalist in this period and later a United States senator from Oregon. Neuberger wrote a little story, back in the early 19 middle, 1950s about, getting off a train in Pocatello, asking the, attendant, who's standing on the siding at the train station in Pocatello if, so-and-so has ever seen around these parts again, he's obviously referring to Glen Taylor, who he knew quite well.

And the railroad, attendant. The guy on the on the on the, siding says, oh, those guys never go back to Pocatello. And in fact, Glen Taylor really never did go back to Pocatello. He moved to California. Never lived in Idaho again after 1956.

This is where he, goes full time into that. He still needs a job. He's never made any money, to speak of his in his entire life. Living pretty much, a hand-to-mouth existence. But he starts his quite successful business, the Taylor Toppers. The, the two pays. And it becomes very successful as one of his sons eventually winds up running the business.

He writes, his memoir, which was published in the early 1980s, called That the Way It Was with me, which, as political memoirs go, is actually, pretty good. His version of, his life in politics. He still very bitter about the 1956 primary with Frank Church, and content continued to believe until the day he died that he had, lost that election because it had been stolen from him.

He died in 1984, at the age of 80. And, in addition to his civil rights career and his long, advocacy of liberal causes, among other things, Taylor helped secure, the funding for the National Reactor Testing Station, which is now known as the Idaho National Laboratory, the big Doe complex in eastern Idaho. He was instrumental in pushing for funding for Palisades and Lucky Peak Dams and after World War II, for the reactor for activation of Mountain Home Air Force Base, which was a base during World War Two.

But then basically was abandoned for a period of time. And he was an advocate for reestablishing Mountain Home Air Force Base. His last words on the Senate floor, as Ros Peterson has written Ros Peterson's biography, by the way. I highly recommend it. It's a wonderful little book. It's titled Profit Without Honor Glen Taylor and the fight for American Liberalism.

Ros Peterson writes of Taylor's last words on the Senate floor, that they, epitomized his idealism. And I quote at one time, Taylor said, I stated on this floor of the Senate and I was going to vote my convictions. And though I as though I never expected to come back here, and all I can say is that I did vote my convictions and I did not come back.

Glen Taylor, controversial, consequential politician, mostly forgotten now to Idaho's history, but somebody who, in my judgment, clearly deserves to be remembered and remembered as a man with, considerable ideas and considerable accomplishment. So, David, I'll turn it back to you.

David Pettyjohn: All right. Thank you so much, Mark. If you could, stop sharing your screen for a moment.

Marc Johnson: See if I can do that. Very good.

David Pettyjohn: All right. Well, thank you so much, Mark. If anybody has a question for Mark, please go ahead and type that into the Q&A at the bottom. Or you can also use the chat feature before I ask my question mark. I just want to point out, like I said to you earlier, that is the most stunning backdrop, that I have seen on a zoom call.

So kudos to your library there. I think, it's a testament to to all of your, interest. And so I kind of want to start my question with, how did you really kind of learn about Taylor, and how did you really kind of develop this interest in him?

Marc Johnson: Well, I, I think, my first recollection of Glen Taylor was talking to John Collette, who some of the, listeners tonight will remember as the longtime political editor of the Idaho Statesman, a wonderful guy who I didn't know until quite late in his life. And he was essentially done being a, a working journalist by the time I knew John.

But I, struck up a friendship with John, and we would often go to lunch together. And I would ask him about these characters that were barely known to me at the time, that he knew all of them on a first name basis, and he sort of interviewed John Corlett. That sort of introduced me to Graham Taylor. I meant to say, when I was talking about how, vilified Taylor was in that 1950 to 56 period, Corlett, rather sheepishly.

And John was far from a sheepish guy, but he rather sheepishly, recounted late in his life that in that 1954 and 56 election, he had been instructed by his bosses at the statesman to go out and destroy Glen Taylor. Those are the words that he used. So he came up with every kind of, charge against Taylor that would, be fit to print and printed them and, really went after, Taylor's character, his patriotism.

And I think John regretted that, for the rest of his life that he had participated in that kind of an effort to, essentially a character assassination, politician. So that was my introduction to Glen Taylor. And, he fits nicely in my, my interest in this kind of progressive tradition among Western politicians of both political parties.

David Pettyjohn: Well, it kind of leads into our next question. Does do you think Taylor's staying power in Idaho? Primary elections show that there's always been a core group of liberals in the state, and, perhaps Frank Church would later adopt them?

Marc Johnson: Yeah, I think no question about it. There's, very much, was a hard core, support from the progressive liberal end of the spectrum. A lot of that, concentrated in northern Idaho and, organized labor in the minds back in those days. But even in the farm community in, eastern Idaho or the Magic Valley, there was a strong tradition of, the Farmers Union and, the National Farmers Organization, which were more way more liberal than the Farm Bureau, for example.

And they supported guys like Taylor consistently. So there was always a core sometimes, and just enough to win a Democratic primary, not enough to win a general election. But that core has been, from a function of Idaho politics for a long time. Frank Church clearly ran to, to the right of Glen Taylor in 1956, but he quickly consolidated, his political base, by incorporating Taylor's followers into his political movement.

And, part of the reason he was successful in doing that is he hired a woman by the name of Gerda Barnes, who had worked for Taylor for many years, and she became his chief of staff, and by all accounts, one of the most brilliant political operatives that Idaho has ever produced.

David Pettyjohn: You mentioned about, how close these primaries were, you know, on two of his elections. He, won one by 216 votes and then lost one by less than 200. Was that pretty common back then or.

Marc Johnson: You know, close elections really were common. It's not it was not, unusual to have, you know, less than maybe 30,000 votes in a contested primary election. And often these primaries were 3 or 4 person affairs. So you could win, with less than, you know, less than a majority. And often that did happen. And it speaks to that, sort of factionalism that existed more in the Democratic Party than the Republican Party, I think.

But it did exist in both parties. So there were factions that were constantly competing to see who would have the upper hand.

David Pettyjohn: So you kind of alluded to this character assassination, that that kind of took place. One of the questions we've received is why have Taylor's accomplishments essentially been forgotten? You know, here in Idaho, you mentioned, you know, he was one of the first to really stand up to to Joseph McCarthy. So, why do you think, you know, that the Taylor's, not as recognized today as some of our other previous senators?

Marc Johnson: Well, I think there's a couple of reasons for that. One is that the victors tend to write the history. And he ultimately was not, not seen as a victor, a one term senator. Who made an ill fated run for vice president on a ticket that didn't do very well. The other thing was that I think by the end of his career, he had been vilified as sort of a, a loose cannon, a bit of a wing nut, somebody who was not terribly serious, the singing cowboy who had somehow parlayed that showmanship into the United States Senate.

And his accomplishments, were largely, overshadowed by that image, that image of being a little bit of a flake, which is really and Ross Peterson really writes eloquently about this in his book about Taylor, that that really was unfair to the guy, that there was much, much more substance to him than, the caricatures, allowed.

So I would just say generally we tend to forget, politicians, my old boss, Cecil Andrus, used to say, you know, the half life of a politician is about 25 minutes. And, once you're out of office, the memory fades pretty fast. I wish we could do more to kind of, buttress the history around some of these figures from Idaho's past.

Because there really is there are some fascinating stories there.

David Pettyjohn: An interesting question we received. What kind of politician do you think Glen Taylor would have been in the age of television? Would he have thrived on interview shows such as Meet the Press?

Marc Johnson: I think he would have been very, very good. By all accounts, he was an excellent speaker. Very comfortable, behind the microphone, a very comfortable meeting people. I think he would have excelled in sort of a modern media environment. And probably would have had that guitar slung over his shoulder so he could break into a song really easily.

Again, Cassandra's remember is probably from that 54 campaign against the worst act that, he's living in, or a Fino at that time, and Glen Taylor coming into or a, you know, driving his kind of beat up, panel truck with the loudspeakers on the top. Glen Taylor for Senate painted on the side. He hops out of the truck, jumps up on the hood of the truck with his, guitar, sings a couple of songs and then, you know, verse two to a draw a crowd around him and then bursts into, his campaign stump speech, which he, delivered with, considerable vigor.

I think it's fair to say. So short answer. I think he would have been terrific on television.

David Pettyjohn: Well, you know, he used his entertainment prowess to get himself housing and, you know, on the on the steps of Capitol Hill.

Marc Johnson: Oh, there's a great story that, that Ross Peterson relates in his book about Taylor was so, you know, hand-to-mouth existence in his early days as an entertainer that he would take virtually any payment for people coming to one of his shows. So a farmer shows up at one of these shows with two chickens and a big sack of potatoes, and he says, you can have the two grand, you can have the two chickens or the big sack of potatoes.

Taylor thinks about it for a second and says, I'll take the potatoes. I think they'll last longer. So, you know, he he obviously had made a life for himself, in very tough circumstances during the Great Depression as a country singer.

David Pettyjohn: Yeah. So who were Taylor's friends in the Senate? Did he work closely with other liberals, such as Magnuson or, Hubert Humphrey?

Marc Johnson: He did indeed. He thought Humphrey. He thought a lot of Humphrey. He was, reasonably close to other Democrats in the Pacific Northwest employing Ward, including Warren Magnuson. Magnuson was a big supporter initially of this Columbia Valley Authority idea. So naturally, he and Taylor, worked together well on that. Taylor claimed, that he had a close, personal relationship with Harry Truman, despite the fact that he, he was quite critical of Truman, particularly Truman's foreign policy.

So, yeah, he he gravitated toward the liberal end of the Senate in, the late 1940s. So it would have been people like Magnuson and Robert Wagner from New York and Humphrey, for sure. Probably not so much Lyndon Johnson.

David Pettyjohn: I mean, probably not. So a question here, and I apologize, if I don't have my timing correct. But, somebody ask, were there any interesting interactions between Taylor and Senator Wheeler? Were they in the Senate at the same time?

Marc Johnson: They they overlapped for, really just two years. So Taylor was elected, in 1944. Takes office early in 45, and Wheeler is defeated for reelection in 1946. So there there was about a two year overlap. I've never really seen any evidence of, the two of them working together on anything, of import, although, they both were big, champions of federal reclamation projects, dam building and that sort of thing in the West.

So it's not inconceivable that they were making common cars on something like that. I have seen a reference to the fact that when, Taylor was running, for the first time in 1938 and losing that House election and House primary, that he was, one of his talking points on the stump was support for what was known as the Wheeler Rayburn Act, the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935, which broke up the big utility holding companies.

And, Taylor was, you know, a strong proponent of that. They both hated Wall Street and big banks. So I suspect there may have been some common cause or possible there. Wheeler was not much of a, he had friends in the Senate for sure, but, not very close relationships. And by 1946, when Taylor would have been a freshman, Witter was very much, among the old guard in the Senate.

Probably not too much socializing going on.

David Pettyjohn: So, as you said, Frank Church defeated Taylor in that very close primary. Two questions about that. The first one. Has there been any sort of a verification or looking back about the vote in Mountain Home? Has any, you know, any further discussion, about that and then follow up question to that. What was church's, thoughts about Taylor?

We understood that you said that Taylor held a grudge for many years after that, but how did church himself view Taylor's service in the Senate?

Marc Johnson: Well, your first question. First, about whether there was any follow up to the allegation that the election had been stolen, particularly in Elmore County, mountain Home. The answer, I think, is yes and no. Taylor tried to do his own door to door canvasing, hoping that people would sign affidavits to the effect that their vote hadn't been counted or who knows what he was really trying to accomplish.

He was not able, in any way that, made any sense, to anybody but him. I think, make a case that the election had, in fact, been stolen. In fact, he did appeal to the United States Senate as the ultimate arbiter of who can be seated in the Senate. And a committee of the Senate looked into the election, committee chaired by Al Gore's father, Albert Gore, senior from Tennessee.

And, the committee concluded that, no, there had not been any irregularities. State Board of canvassers, dominated by Republicans, determined that there hadn't been any irregularities. Church, I think, considered Taylor a sore loser. And sort of a perennial candidate who needed to essentially go away. And, but fundamentally a sore loser as late as 1958.

Taylor was writing a letters to church asking him to take a lie detector test about the fact that, he had stolen this election. Could he could he pass a lie detector test on the basis of what he knew about the election church? Probably for good reason. Blew that off. Didn't pay any attention to the allegation.

So, Yeah. To your earlier question, David, I think one of the reasons that Glen Taylor is sort of remembered as a crank is because he didn't handle that very well. Needless to say, he prolong the agony of his own loss and, as I said, went to his grave, maintaining that had been stolen from him.

David Pettyjohn: So you had posted a news article, about Taylor's 1944 candidacy for the Senate, and it listed him as a war worker. What more can you tell us about that reference or other aspects of his social or work connections in Pocatello during the war, and how much might this context have shaped his political positions?

Marc Johnson: Well, that's a great question, actually. Between his various runs, 1938 for the House, 1940 for the Senate, then again in 1942, and then in 44, he basically went back to California after each one of these elections because he could get, work there more easily. He had given largely given up the, musical touring group at that point, and he was looking for a way to make a decent living for his family.

So he went back to the Bay area, worked in the defense industries. As I recall, you know, shipbuilding and that sort of thing. That was, was, prominent in the Bay area in, in the early 1940s, middle 40s. And then he would come back just in time to, you know, file for election and run again.

So he worked in a variety of war industries, but not so much in Idaho as out of state.

David Pettyjohn: So I think.

Marc Johnson: It did shape his, his views about, economics because he really was concerned about what's going to happen to all of these returning GIs coming back from the war. There going to be jobs for them. What's the economic conditions going to be? What are the economic conditions going to be in the country? And how do we take care of these guys and their families when they come back after, serving in the military?

So it was a big concern of his, for sure. And a concern of a lot of people.

David Pettyjohn: Any information on what his family, his descendants are doing now?

Marc Johnson: I believe a rod, Taylor is still alive, living in California. He's a dentist. Two of his two of Taylor's sons turned out to be dentists. One of them sort of inherited the toupee business and was quite successful with that. I don't believe the Taylor Toppers are still in existence. I think the company was sold, some years ago.

But at least a couple of the children are still still with us. In fact, Senator Sherrod Brown, I mentioned his book. He quotes, A-Rod Taylor in the book about, his father and how proud he was of his civil rights, activities in particular. Commenting, A-Rod commenting to Senator Brown that, his father was proud of the fact that he had been in the Birmingham jail before Martin Luther King had been in the Birmingham jail.

David Pettyjohn: We just have time for a few more questions. So, Senator Taylor, you know, as you pointed out, was very, outspoken about racial injustice. What do you think? It's always difficult to kind of imagine, but one of the questions we have is kind of his thoughts on what we are, discussing today. Right now.

Marc Johnson: Well, I'll start with my usual caveat about such questions. I think it's impossible to know how a figure from the past would respond to contemporary circumstances, but I do think, you could have some comfort in asserting that Glen Taylor would, have been very involved in the moment right now because he was very involved in the moment, when he had an opportunity and a platform to speak out about civil rights and voting rights in particular.

And he went really in, in some ways into the belly of the beast by going to Alabama, Mississippi in this period and campaigning with African-Americans, on issues like getting getting them registered to vote. Eliminating things like poll taxes to keep them from voting. So I, I, I, I hesitate to extrapolate his views from the 1940s or 50s into the, to our current day, but I would suspect that those were some of the ideals that he, held very firmly to throughout his life.

And I suspect he would have found some way to be engaged in this moment in a pretty important way.

David Pettyjohn: So somebody has, shared a story, I think that was in his book about how, you know, when he started out, you had mentioned riding horses everywhere, and that, he it was kind of painful kind of doing everything. And that's kind of where he learned how to use, I guess, baby oil to, to help soothe that.

And, it was from a woman in the Panhandle, I believe. So I don't know if you've you've heard that story somebody had shared that.

Marc Johnson: I have heard that story as a matter of fact, that, you know, you have to be careful. You can get, some chafing if you spend too many hours in the saddle.

David Pettyjohn: So, so one last question. Actually, I'll end with one more. But after this. So the D. Worth Clark lose that1944 primary to Taylor because Clark was an isolationist like boor and Wheeler, and the position was discredited. How do you think that played into the the election?

Marc Johnson: I think that very much played into the, worth Clark's election in 1944. Pretty much every member of the United States Senate who was identified with the isolationist or non-Native earnest, movement prior to World War Two, and this would have been people like, certainly like Senator Wheeler Worth. Clark. Gerald Nye from North Dakota. They all, lost, their postwar reelections.

So, in some respects worse. Clark was kind of about the leading edge of that losing in 1944. But Wheeler and Gerald Nye and, Senator La Follette, Robert La Follette Jr. from Wisconsin, they all lost in 1946. And they were all clearly identified with that, isolationist noninterventionist wing which had fallen completely out of favor as a result of, U.S. involvement in World War Two.

So their positions really were repudiated at the ballot box.

David Pettyjohn: So last question. I want to thank everybody for taking the time. There are many we didn't get a chance to answer, but do you think, Taylor could be elected to any political position in Idaho today?

Marc Johnson: I think that would be tough. Maybe maybe a local race in, in Blaine County or Ketchum or something. Beyond that, I would think he would be, pretty far to the left for, most, political taste in Idaho these days.

David Pettyjohn: Well, Mark, thank you so much for joining us this evening. A lot of fun.

Marc Johnson: And, David, thank you. You did a great job of moderating.

David Pettyjohn: Right back at you for for the presentation. I told, Mark, this was my first time, so thank you so much for that. Everybody, thank you so much for joining us. We look forward to seeing you next Tuesday for our next discussion where we will have Richard Blanco, inaugural poet, speaking on To Love a Country. Just special note that next week it will be at 7:00 mark.

Thank you again so much. And everybody have a wonderful evening.

Marc Johnson: Thanks, David.

David Pettyjohn: Thank you.