Dr. Jennifer Stevens

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

Doug Exton: And it is 6:00. So I just wanted to say welcome and thank everyone for attending tonight's first connected conversation hosted by the Idaho Humanities Council. This conversation will be hosted by me, Doug Exton, a program officer here at the IFC. Joining me here this evening is Doctor Jennifer Stevens from Stevens Historical research associate. If you have any questions during her presentation, please do is the Q&A feature.

And then at the end during our Q&A, you can also use the Raise Your Hand feature to ask your questions publicly. So, Doctor Stevens, take it away.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Okay. So this is a really strange we can all admit that this is a little strange. You can see me. I can't see you at all. Which means I'm talking to a black box, which is a little weird. But I did look at the list of attendees. Doug was kind enough to send that to me before. And I know many of you who were on the call.

And it's especially fun for you because, I'm. I also teach at Boise State. And Doug, was one of my students, and, was a history major as well as an urban studies major and just graduated. So it's really fun that we're getting to do this together. And I'm excited that he asked me to to do this conversation during our Covid, disaster that we're going through right now.

And I'm sure it's a beautiful day out. So I appreciate that you're all with us and choosing to spend this hour, with us. So I'm going to be talking a little bit about some of the research that's preoccupied me for the last several years and some, some work that I've been doing under both the National Endowment for the Humanities grant, as well as a grant from the Boise City Arts and History Department.

Both of whom have been very supportive of the work that I've been doing. So I actually have some new ideas I'm testing out on, some of you tonight. And then I know that there are a couple people on the call, a for another former student, who's probably heard some of this before. So, hopefully some of the new material, will catch your eye and some of the new thoughts I have about this.

So the name of the talk, and I'm going to go ahead and share my screen now is this ain't going to be no lunch bucket town or this ain't going to be a lunch bucket. And I didn't actually have him on record. When I got that quote, which I'll tell you about for a while, but this is, a discussion today about urban identity and how it's shaped and in particular, how Boise's urban identity has been shaped over the last 100 years or so and how it's changed.

And I'm going to start by saying that, Boise's identity today, which is I think many probably everybody on the call would agree is represented by sort of this recreational friendly, outdoor quality of life vote thing that we've got going on. It's reflected in our city's current planning documents. But that that identity that we have today, I'm going to tell you my opinion is both a story of loss as well as one of resilience.

The loss that it represents is the loss of the city's rich industrial past. And that's mostly what I'm going to talk to you about today. And it's also a loss of the people to whom that past belonged. And of course, the story of resilience is the one of choosing a new identity, the one that we're all living with today that can carry the community into the future.

So there are typically two key drivers of a city's identity. The first is its setting and surroundings. So the things that a city can't really do anything about, but typically are the things that drove its its birth. Things like rivers, lakes, mountains, ports, forests, minerals, etc.. The second, though, is what a city and its leaders, both elected leaders as well as citizen activists do with those surroundings and what they make of them.

And so the Boise of today is quite different in terms of what it's made of. Those, those, natural resources than the Boise of 1860. Now, that's probably not surprising to any of you. A lot of things have changed over the last hundred and 60 years. Major technology changes. Cars to airplanes, to computers. But there's more to Boise identity changes than what happened on a national and global scale.

There were people in this town who made a choice about what we were going to be and what we were going to portray. We were to the nation and beyond. And the choices that city leaders and citizen activists have made have had long term impacts on both the profile of our city as well as the demographics of the people who have chosen to stay here.

Those who have chosen to leave here, and those who have chosen to emigrate from other places for the jobs that we offer. So I'm going to talk today. And I probably have tried to pack too much into the talk already, but I'll try to fly through it pretty quickly. We're going to talk about that transition, the transition of our identity from industrial city, which a lot of you probably don't know much about to what I'm going to call today's Green City and why the leaders are elected leaders in particular, might not have wanted Boise to be a lunch bucket town with blue collar workers and instead thought sort of this white

color identity that has had really important and far reaching racial and socio economic implications, some of which I'm still very much in the process of researching and learning about. So, the genesis of this project, just very quickly, there's a yellow arrow here in the corner that points to, what was used to be known as the Gate City Steel site.

And, I was sitting at a planning and zoning commission hearing, back in 2016, and I sat down with the Planning and Zoning Commission when developer Bill Clark came along and said he wanted to build, 67 houses on this little spot right here. And just to orient everybody, this is, the municipal golf course is right here.

The old Idaho pen and the Idaho State Archives. Some of my favorite places are right here. And Table Rock is right here as well. And so Bill Clark came in front of planning and Zoning, and he said, I want to build these houses on the old steel site. Now, I'm a I'm a historian of Boise, certainly, but I'm also, I do a lot of work in industrial history around the country, and I'm in, an environmental history.

And I had never heard of the Gates City Steel site. I was quite surprised that there was such a thing, and it really piqued my curiosity. And, I was I was perplexed, wondering where on earth all the remnants of this gate to this steel site were. And how I had grown up in this town had never known that there was such a thing there.

So before, Mr. Clark's development went up, which is still in the midst of being built, but, is definitely. It doesn't look like this anymore today. This is what the site looked like. So this is sort of a what I call an in-between time, right between the time gate to be steel site got torn down in the 1980s, actually burned down.

And the time that, the developer began building houses here and I was really quite again, curious about what else I might not know about Boise. I, you know, I had always sort of assumed that Boise had always been about, fishing and hiking and boating and camping, but I began to question Boise's urban identity and wonder what else had been erased.

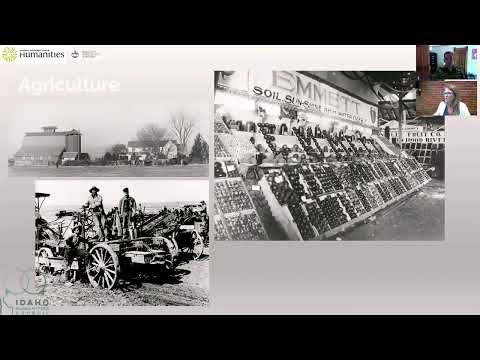

In the process of greenwashing Boise. This is what I knew before I started this project. I knew a lot of you probably know which is the history of Boise agriculture, and a lot of this probably won't be very new or surprising to you. The state and the city were both really born out of the natural extraction possibilities that this valley had to offer.

So, of course, Boise is surrounded by the foothills and the Boise River, and the river really was the driver of the city's founding. It provided water, fish, animals for fur. The fur traders came in the 19th century and the early 19th century, while the United States Army, of course, established a fort here several decades after that.

The mountains surrounding Boise were also quite important. Up the river, up Boise River near Idaho City, gold and other minerals of value were discovered in the early 1860s. And it was that discovery that really brought, the first wave of, of more permanent migrants to, what became the city of Boise. And the Treasure Valley. Closer to home in the valley itself, government surveyors were, busy surveying the land to determine, what basically to take inventory of and to determine where people could, homestead and create farms and, in the process of doing that, they also noted that the Boise foothills were extremely valuable for grazing, and that brought,

some of our, well known Basque immigrants here for shepherding, and, then of course, the farming started as well. But it wasn't until 1902 when Congress passed the Reclamation Act that the Boise Project was born. Everything up until then was, stop and go. I mean, there was they had a hard time. The private entrepreneurs who wanted to build canals and take water out of the Boise River to farm, had a hard time, with financing those huge endeavors.

And so it wasn't until 1902 when the Boise Project was born. I'm sorry the Boise Project wasn't born in 1902, but the Reclamation Service was born in 1902, which then ended up funding the Boise Project. That farming really got off the ground in a really, pretty major way. And, of course came the type of thing that you see here and, up on the right here.

This picture is a photograph of, of some of the produce that came out of Emmett. Boise. The Boise project not only included the Arrowrock Dam, but also the Black Canyon Dam up on the river. And, some of the major produce centers were, in the Emmett area from that time. But of course, to deliver that water and to use the money that came from the newly created Reclamation Service, which we know today as a Bureau of Reclamation, we needed some people to do that work.

And, lo and behold, the company by the name Morrison Newton was born, out of its bid to build the New York Canal. And it was one of our first big manufacturing industrial companies. That set the tone for what Boise would become. And excuse the street noise. My, office is located right on Main Street, and it's a lot louder than it was just a few short weeks ago.

So this is, just a picture of, some of the workers building the New York Canal in 1912. This is a photograph of, the Boston and Idaho dredge up in Idaho City from 1914. And you can imagine with Boise's, isolation geographically, that, transporting a machine like this from, say, Salt Lake City or Portland or Seattle would have been quite a feat.

Now, I don't know 100% for sure that this was built in Boise, but my my hunch is knowing what I know about Boise's industrial history now, that at least some of the parts were forged, in fact, right here in our valley by companies like the Baxter Foundry. And then later, maybe a Gate City Steel might have fabricated some of the, some of the, machine parts that were required and things like dredges.

And then, of course, in addition to agriculture and mining, we also had a major timber industry. And, the timber was utilized for many things, but, some of its biggest and most important uses were for, propping up the mine tunnels. Which required an immense amount of wood. And then, of course, forging the railroad ties that would bring goods and, goods in and out of the Boise area.

And so the forest surrounding, Idaho City became, the important site of the timber industry. And, of course, what happens when you start extracting all of these natural resources, whether they're water or, minerals or timber, you begin to have to serve those natural resource extraction sectors. And so, as I already mentioned, Morrison, Newton was one of the, first companies that was born sort of in this era.

But we also had, an iron foundry which was situated, which I'll show you pictures of in a minute. Situated right at the base of the Boise depot that we know today and love so much. So a really nasty, kind of dirty iron foundry was right there. Gate City Steel, situated right on the Boise River at the end of Warm Springs.

Many lumber mills, and lumber yards that were scattered throughout the city, which I'll show you in a bit, of course. Quarries, many slaughterhouses, that dumped their wastes into the Boise River, which was sort of a industrial sink, if you will. Machine shops like the Yankee Machine Shop and many more. And all of these industries were really, founded to serve the natural resource extraction sectors.

And so this what you'll see is, the underlying this is what's called a Sanborn map. It's an insurance map. Done by the Sanborn insurance company that used to go out to cities and, truly inventory every single building within the city limits so that they would know what their fire risk was. And so it's a really nice, way to do historical research.

And what you can see here. This is upstream the Boise River. This here where I'm circling the yellow yellow square is, the original Boise plant. So the very core of downtown. And this down here is what we know today as Simplot, Esther, Simplot Park and the Whitewater Park. So you can see all along the river we had slaughterhouse Six.

We had heavy construction, sand and gravel. Not all at once, of course, but in the course of the first 50 years or so of the 20th century, these are the types of things that, built up in the Boise area, just right outside the Boise downtown core. Of course, the rail came directly through the middle of city of the city, and, served all of these various industrial interests.

Upstream, we had a lumber mill, brick and tile company up. And what we know today is Harris Ranch. So back in the, in the Barber Valley, but you can see there was really, you know, in the, in a really small area about four miles, from one end to the other, we had quite a lot of very serious industry, heavy, fairly heavy industry in, in the downtown Boise area.

And this is just another, more modern view. Just so to get you situated again. Lucky peak is up here. This is one of those Sanborn insurance maps. Close up of the Gate City Steel site right there. Sand and lime company here and, some other, map representations. I do, in my time.

615 so this is, I'm just going to show you a few photographs here so you can, just get a feeling of what? Of what things looked like. I think people tend to do best with photos, in terms of really trying to imagine a place. So, this is actually the Bill Clark housing site, if you can believe that.

This was, the Boise Stone company and I don't have a precise date on this photo, but my guess is and I know Terry and a few other people from Boise Arts, some history here. My guess is that this is about 1908 or 1910, and they want to weigh in on that and tell me what they think. I didn't have a specific date, but this is the site before it became the Boise game against a steel factory.

And then here it is in its next iteration. This is, it was initially called the Olson Manufacturing Company. Before it was purchased by a company in Nebraska, Omaha, Nebraska, called the Gate City Steel Company. And that company actually also had a facility over in Pocatello. So this is a picture of the Olson Manufacturing Company. And this is the same site again.

But, when it had become Gate City Steel, this is probably taken in about 1955. Would be my guess. Now the Gate City Steel Company made, they didn't make steel. So, you know, you may be thinking about Bethlehem, and those sorts of big steel Pittsburgh companies, things like that. They were not actually making steel in this factory.

What they were doing was they were fabricating products. And so some of the things that came out of this, this, factory or this fabrication plant were some really important inventions. One of the things that's been great about this project and, one of the things that I did with the grant from Arts and History, the Boise Arts and History department, was to do several oral histories with people who worked in some of these places.

And there was a, there was one interview. And I'm going to I'm going to give you a quote from, one a little bit later in the presentation. But, one of the interviews told me about, one of the interviewees told me about a machine that he made. He was it turned out he was actually an engineer.

It was Hugh Hartman. And, he had a gentleman come to him from Ontario, actually a Japanese farmer who had been in the, in the camps in Minidoka. And when he when the war was over, after World War Two, he went out to Ontario, Oregon, and started a farm and he came in to, the the Gate City steel plant, and he asked Hugh Hartman to make him a very specialized sort of tractor implement that you can put on the back of this tractor that would, I forget specifically what it was, but had something to do with picking strawberries.

And so, you know, it was this massive machine that that Mr. Hartman, made and designed in this factory. And, it really was, you know, it never was made again in that particular case, but, people would come here for, specific implements. They needed to serve, again, those natural resource extraction industries. This is a photograph of the Baxter Foundry that I told you about.

So, this is probably standing right, at the probably around the train station or just right underneath the train station. So very different than what it looks like today. This is an aerial shot of, believe it or not, a Ford auto assembly plant that we had. This is, Main and Fairview Avenue, so probably recognize that that sort of area right there.

And of course, the Boise River, long before it was channeled the way it is today. And then here's a photograph of, one of the lumber lumber yards. Of which there were many in the city. So want to make sure that I leave enough time to talk about, the transition. Right. So, here's just another another listing of, some of the many industries that we have right downtown.

And one of the things, as I've been giving these talks over the last couple of years about this research, I have really come across some wonderful people in the city, some citizens who have given me leads, some really good people to talk to, as well as, companies that I may not know about yet. So if any of this looks familiar or you have a relative who worked here, at any of these places or some other place, please be sure to send me that information.

And, Doug, I'm sure can get you my my, my contact information, because I'd love to talk to them. So I just wanted to give you this one excerpt from the Hugh, another excerpt from the Hugh Hartman, interview. And he was telling me that in addition to the crazy, sorry about that of, of the strawberry picking implement that he made, he also did something that ended up becoming, an important patented invention.

So one of the things that that he used to go out to the farmers, in addition to them coming into him, he would go out and say, you know, what sort of things do you guys need to make your life a little bit easier? And I guess when you used to harvest beets, used to take a beat in your hand, and you would have a knife and you would singularly have two sort of top, top of each one at the time.

And, Mr. Hartman was, was very excited because he told me that one of the things he designed from steel was something he called a rope, a roto beater. And so they could take this thing out into the field and do four rows at a time. So it was a really important entrepreneurial, invention that came out of our little Boise, Idaho that we never think of, as industrial.

So. So what's changed? Well, a lot, this is, one of my favorite, favorite images that I have found in all the research that I've done. And this is comes from an Idaho Power annual report from the 1960s. And you can see, that what we really thought of as progress in the 1960s might be a little different than what we think of as progress today.

Not entirely. I mean, some of it's still certainly accurate, but this was really the dominant narrative, processed foods, factories, you know, cut down logs. And this was this really is a moment in time before the dominant environmental narrative sort of took hold of the country and took hold of our city. So I like to use that as sort of a representative of what, what Boise and what Idaho, had been certainly, in the years before that.

But today we get off the plane in the Boise airport when we can travel back in the good old days and, we are greeted with signs that say, making Boise the most livable city in the country. And so, you know, my research has really been about trying to get from one to the other and explaining, and understanding myself how we got to those from that one thing, the industry and the, you know, the different factories along the river to what you see here on this particular slide.

And part of it, of course, is the growth of the environmental movement. In the 1960s, we had obviously a very volatile, decade in the 1960s, which had to do with many things, but one of which was, rising and an increasing understanding of our natural environment and appreciation for the natural environment. This, this slide in front of you right now, though, talks a little bit more specifically about how this played out in Boise.

So I'll say, I say this a lot and I say it sort of with With Love in my heart, Boise tends to be about ten years behind on a lot of things. And my students have certainly heard me say that in the past. And we were very late to the party when it came to adopting our first comprehensive plan.

By the time Boise adopted its first comprehensive plan in 1963. You know, urban planning had been around for decades at that point. So we were definitely really late to the party. And, it also happened to be the 1960s, was sort of the second decade of what many of you on the call, I'm sure, have heard of called Urban Renewal.

And Urban Renewal, for anybody who has studied cities or studied the 50s, in the 60s, those two words often leave a bad taste in our mouths. It usually it often meant the destruction of neighborhoods. That often meant the construction of freeways through lower income and minority neighborhoods. It meant the tearing down of historic buildings. And, it was not, not an era that, urban planners are very proud of today.

And so here we were, Boise, adopting our first comprehensive plan, sort of in the middle of all of this. Right. And, but what was interesting is that that comp planner, in a small, little, small little line in the comp plan, that he wrote, he said something like, you should really focus on the river. And that's really that could be a really neat amenity.

So sure enough, the Boise City Council, hired a local planner to design the Boise River Greenbelt Comprehensive Plan. And that was adopted in 1969. At the same time that that was happening, though, we were, what what this article here on the right says tearing our city down. Much of what we were doing in our comprehensive plan was getting rid of the old and trying to build new, and actually, it many of the policies of that time period, were tearing down buildings simply to build surface parking, something that would be, unthinkable today and something we try not to do.

But at the same time that we were tearing down the city, we were also building it up and really focusing on, this greenbelt. And that was really one of the first, things that the city did that indicated, elected leaders decision, along with citizen activists, no question about it, that the city could adopt this new identity.

There were some other things that happened during these this ten year period, too, from 1963 to the time that the first section of the Greenbelt opened in 1975. HP Hewlett Packard moved here in 1973. And then just a couple of years after the Greenbelt opened, micron was founded. So we've got this confluence of factors happening during this time period from 1963 to 1975.

We have environmentalism rising, right? We have, the adoption of environmental laws that are making it very hard for some of those industries that were situated here in Boise to continue dumping their waste into the river because of the Clean Water Act. And we also have now zoning ordinances in the city of Boise that are pushing industry up to the outskirts.

So you've got this environmental movement going, you've got comp planning moving up, and, the city taking greater notice of what we can do with zoning and comprehensive planning. We've got industry moving out, and we have an embrace of the greenbelt and eventually the river and eventually the foothills, too. And so we sort of begin to see this morphing of industry moving out and an emphasis on amenities that are more attractive to not necessarily more attractive to, but certainly, cater to white collar workers who have more leisure time.

Those people are moving in, and we're, as a city, beginning to embrace the kinds of things that those white collar knowledge workers, really moved to a place for. And so I, you know, I believe that the Boise River Greenbelt was actually, part of urban renewal, which is sort of a weird thing to say. It's not, I think that, I'd be interested to hear what some of you think about that, but I think you can't look at the rise, the greenbelt, and the rise of our green identity in the city without, understanding the context within which, those things were being embraced.

So I've got one more little timeline here that that sort of shows you on the top the rise of the green identity and sort of our embrace as a city of parks, all the way up to the whitewater park construction and on the bottom, industry, you know, that started the mining boom and the frontier town moving through increased manufacturing, from the 19 tens through the 1950s.

And then that passing of the zoning code and the comp plan and the, of course, arrival of the modern environmental movement. And so I think it's really interesting to look at these two things together side by side and sort of trace their, their march through time together to understand what the relationship is between the two of them and try to understand why.

And this is something I'm still trying to understand, why there's so little trace of our industrial past left in our city, and why so much of it has, in fact, been greened over in this sort of striving for a new green identity. So, I will lastly show you what what the same map looks like today to sort of, show you where, you know, where all those slaughterhouses and, iron foundries and, steel factories and such were are now green Belt city parks, trails throughout the foothills where some of the slaughterhouses used to be, etc..

So we have really greened over a lot of that blue industrial past that, we had and that defined our city for many years. And then finally, I'll just leave you with some of the questions I'm still doing research on. This is certainly not a complete project by any stretch of the imagination. But, these are some of the things I'm still asking, and I'm really looking forward to your questions and looking forward to, your thoughts on some of this.

So thank you. So much for having me.

Doug Exton: Alrighty. Thank you for that wonderful presentation. We will now be taking questions and it looks like we have one right here. It is saying data.

Can you speak to the, core corporate corporatization of agriculture and the loss of small farms and food processing plants? Many blue collar jobs were lost to this economic shift, led by large scale potato production drive driven by Simplot. Also, how does Boise's experience of losing blue collar jobs mirror the US's loss of those same types of jobs?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Those are great questions. So I can't necessarily speak. I haven't done much research on the corporatization of farming. That's kind of a whole different research topic, I guess, and certainly extremely relevant to what happened in our own valley, but I can't, unfortunately. Speak much to it because I just I haven't done the research about it.

I can address, a little bit the, the second question, which is how the loss of blue collar jobs in Boise mirrored the United States, of those same types of jobs. So the framework of this whole research project is to try to understand deindustrialization in the West. So much of the scholarship that has been done on deindustrialization has been really focused on the Rust Belt, which tends to go from, you know, the Buffalo area in New York down through the Midwest, Detroit and, those sorts of areas.

And, what really struck me when I, when I started digging into gates and steel was how little there was to to find out about the West and deindustrialization in the West. And, a couple of my students, Doug, and then another student was signed up, have have been helping me. We've been running urban field schools at Boise State University.

Where urban, urban studies students, have been doing lab work to try to understand exactly the kind of question you ask, which was, you know, is Boise's experience. Can we use the model, the scholarship model, and the findings for deindustrialization in the Rust Belt to apply to places like Boise, or is it or is Boise different?

Is the West different? Is the Intermountain West different? And so my students have studied both Seattle and then, we were supposed to study Oakland, California this spring and, and go on a trip there to do some field work. But unfortunately, as my family likes to say, we shrug and we say Covid. So unfortunately that happened. So, you know, I think that, I mean, that's a very long winded answer to what should be a simple question.

I think that, again, we were a little behind the times. So, the loss of blue collar jobs in one factory towns, and I you I don't really mean necessarily one factory, but, like, if you look at Pittsburgh, which was really dominated by the steel industry, you know, their losses were much bigger than Boise's losses, and much, much more painful.

And they also happened earlier. So, there are differences, but certainly what I have found is that just trend wise, Boise's losses do. And the trends that we see here do mirror, other places just sometimes difference our differences are in volume, or in timing.

Doug Exton: Another question that just came in is during your research, what would you consider the most surprising industry that existed in Boise's history?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: You know, I think what, what is probably been just the most surprising and maybe it doesn't surprise you, because now that you've heard it, you kind of go, oh, yeah, of course that makes sense. But to find out how much machinery was actually being made here in Boise was less surprising. So, there was a Gate City Steel Company, but then there was also Pacific Steel.

We also had a US steel, a very small US steel representative here, or representation here. But then we also had machine shops, fabrication shops. So it wasn't just Gate City, it was also Yankee. Some of the other names are sort of escaping me right now, but we had, you know, quite a lot of machines and tools being forged, made right here in Boise.

And I think that was the most surprising thing, just because, you know, I think when you live in an, in an auto oriented world, you just you forget that it wasn't so easy to move those things back in the day. And so, you know, to, to learn that we had to make some of those things here and, and have a way to make those tools available locally was probably the most surprising thing.

Doug Exton: Actually, going off of that, I wanted to ask a question. How much do you think Boise's isolation played into the amount of industry that we have as a city, or we have?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Yeah, I think it was really critical. I think the fact that we were so far removed from, any other urban area, I mean, I think we are still the most isolated, city in the country, if I'm not mistaken. And so I think that that was a really important, important thing. And in fact, when I interviewed the folks at these various places, that was what they said to I mean, I think that they were able to, be a good salesman.

A lot of them were salesmen that I spoke with. They said it was very easy to sell things because there was no transportation cost, you know, so they could offer things at a cheaper price, than if they had to if these farmers or these other, you know, miners or whatever had to buy these things from out of state, they would have to transport them.

So I think that that was an important driver of the fact that we were that we were isolated. I see some good questions.

Doug Exton: So this one is, about the Reclamation Act harnessing water and yielded hydropower. It was common in the late 1800s and early 1900s that manufactured a gas, was common for gas lighting. Did Boise have a manufactured gas plant?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: So, I cannot give you much information about it, but I believe that we had one right at the foot of the ninth Street Bridge. And it's possible that Amy Sackler maybe if Terry's on the, call, they might be able to verify that. But, it was there was something. But I have not found much, if any, real information about it except for seeing it on one of those Sanborn maps.

Doug Exton: Yeah, and I can attest to that. I've definitely seen that once. It was Boise Gaslighting Co, but.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: I thank you, Doug.

Doug Exton: Okay. So, then Amy actually, said if there was a union present in any of the industries.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: I am really glad you asked that question. So one of the that's maybe been, the biggest surprise and one of the most fun things about historical research, and I suppose any research is that you you don't always know where it's going to go. And one of the most interesting things that's happened is that I have realized that this story may very well be a story about how we became a right to work state.

And, so the answer is yes. There were some unions, but they were fairly rapidly dispensed with. So particularly at Gate City, there were two strikes, 1 in 1966, I believe I might have the dates wrong. And then what, a couple of years later, the people that I have interviewed from the plants, were absolutely 100% to I haven't found anybody yet who was pro-union.

The people that I have talked to, and I'm not saying it's a representative sample, but we're very much anti-union. And so even, even back then, there was quite an effort to keep the unions out of these shops. And so one of the things that, is a new avenue of research that I just barely scratched the surface of is trying to figure out what that what that story is.

And Savannah Willits, who's on the call with us, and is one of my former students, actually helped me with a little bit of that research last summer. And she worked on the the National Endowment for the Humanities grant with me. And so, I'm hoping to, to have that be the a chapter of whatever this turns into, because that's definitely an important part of the story.

Doug Exton: And I think that will be a really interesting chapter to read. And we do also have a our first question in the Q and A, it is I understand fish canneries were common along the Boise River because of the salmon runs. Have you determined the size of this industry?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: I have not actually. And it looks like maybe Mr. Pettyjohn knows how to answer that question. Is that what I'm seeing on the Q and A from?

Doug Exton: I understand because I like the answer. Lies.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Okay. Yeah. Gotcha. Yeah. No, I actually, I have not seen I'd be curious where specifically those were because I have not seen evidence of those. So I would be pretty interested in knowing more about that if you know.

Doug Exton: We also have a question to what extent did Carol MacGregor's book Prosperity and Isolation inform your research?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: So I have read Carol's book. But to be honest with you, it has not. And done. I mean, most of this research has been from research that I have done over the years. And so, you know, it's a fabulous book, but hasn't really formed the basis of, what I've been what I've been working on.

Doug Exton: Another one that came through is the Land Use Planning Act, published by the League of Women Voters in the early 70s played an important role in transforming perhaps the industrializing central areas of the city. I guess that's more of a talking point than a question, but.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Well, and Gary's exactly. Gary's exactly right. So the League of Women Voters was, actually critical. They held a really wonderful conference in 1972, I think it was called, I think it was, called As We Grow or How We Grow or something like that. And in fact, the League of Women Voters, around the country at that time, in particular in the West, in Portland, in Boise, in Los Angeles, in San Francisco, was absolutely critical in these growth discussions.

And they are kind of all over the historical record in the early 1970s trying to educate voters, about that land use planning, certainly, but also about questions in Portland, for instance, about the, the, urban growth boundary and, other types of questions. So, yes, I think, the League of Women Voters have, in fact, this is a another project that I, that I wrote on extensively about about a decade ago was all about women's roles in, in urban growth and in, the preservation of open space in urban areas.

And so, I'm glad you brought that up. And the League of Women Voters is they're still my heroes. They did a lot of really great work and still there.

Doug Exton: What would you say is the most impactful industry voice you just had on both our old identity and our new identity?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Oh, boy. You could argue for a lot of different ones. I think, you know, you really could, I could I could sit here and make an argument for about three different ones, but I guess I'll stick with agriculture. You know.

The irrigation and the the so-called reclamation of the West, I think can't be overlooked is a really important, driver of settlement and, the history of this area. And so, you know, again, even though the, the initially that was an extract and sort of an extractive industry, I guess you could call it, you know, it inspired you, you know, the creation of these tools that I talked about.

But I also think that, there is some conservation that has come from the agricultural industry, actually. And I think that some of the and this is going to be a little bit of a nuanced argument, but I think that, you know, some of the, the water use that the agricultural industry has made, both in taking water out of the river to apply to our fields, but also then the return of that water to our river, with pesticides and stuff.

Those are not, that series of water use and water, you know, water use. I guess I'll just leave it at that has really, had an impact on, Boise in particular because, you know, it's all related to the Boise River, and it goes from back in the day to when we settled this, this valley for farming, to today when we need that river for the things that the amenities that drive our identity, our identity today.

And so, I think agriculture, you know, can't be overlooked as being at least one of the top two most important, sort of industries that we've had has shaped our identity here in the city.

Doug Exton: And then how do you think our new tech and green identity will impact us in the future, given your research of Boise?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Well, I think what we're struggling with now is, is trying to understand how to balance the, you know, we've created this wonderful. I mean, I'm probably I'm probably not the biggest Boise lover on the call because I bet there's a lot of them out there. I'm certainly a huge love I the city is like my my heart.

But I think what we what we've done by making it such a place that so many people want to come and it's so popular when we're written up on every list of there is imaginable. What we've done is we've, you know, we've done that old thing called loving, a resource to that for loving a place to death.

And so really struggling with now is how to balance, the preservation of these places. The, you know, the, the we've built a greenbelt, for instance, right up in the floodplain makes it really hard for us to, preserve our floodplain and restore the ecology of, of our river. And so, and, and the same is true for the foothills.

So I think that we're really, you know, as a city having to struggle with how to preserve our resources, that we have sort of, opportunistically exploited to get people to love. Right. And the question is, does love of recreation lead necessarily to love of ecology and love of preservation? And I think that's sort of the biggest thing that, as our identity continues to be this, this green recreation quality of life thing, we're going to need to, as a city, make sure that we, you know, fall on the side of, of preserving those things and preserving those resources.

Doug Exton: Yeah, I definitely, really, really agree with you on that. And my personal work with you, you know, exploring the greenbelt, I definitely would say that we have loved the greenbelt and the amenities to death on that. Yeah. We have another question that just came in based on your, based on our industrial history, what types of modern industries would be a good fit with our landscape?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Thank you. Alex, that's a great question. You know, I, I will say I'm a big fan of, green industry. So, I look at opportunities for solar, opportunities for, you know, I think that we can have green, green, tourism here. And I think that, if we do it sensitively, I think that those are two huge and really important economic, things that we could do for our valley.

So I think those are, important. But, you know, we do have to figure out the farming, too, because we all do still need to eat. And so, you know, I think ag needs to continue to be an important part of our value. It remains part of our our past and important part of our past. And we don't we certainly don't want to let that go.

And so we need to be careful not to eat all of our farmland up and, and maintain, you know, our farms, such and such as they are, shouting back out to one of the earlier, to Clare, Claudia, I guess it was who made the point about corporatization of farming. You know, obviously I, I think I'd like to get back to small farmers and or independent farmers at least.

But I do think that ag is an important industry that needs to, be protected in our valley.

Doug Exton: Yeah. I feel like having the green energy and the green tourism would fit really well with our current identity, and it almost seems like it would be a natural transition into a new industry for us, given the way Boise has gone and is currently going.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Yeah, definitely.

Doug Exton: While we wait for another question to come on, and is there anything else you would like to enlighten us on with Boise's industrial past?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Not really. I mean, again, I would just ask that, if anybody knows, has relatives who ever worked in these industries, I'm still, doing research, although I am finally writing some of it up. There's an essay coming out in a, a book about Western rivers and the struggle between, whether or not, you know, increasing recreation and stuff hurts or harms our resources.

And that book is, coming from, a guy who's editing it from Gonzaga. He's a professor from Gonzaga. So I'm writing some of this up. And that essay will be coming out in the next year or so. But the research continues.

Doug Exton: So, you know, we do have a question coming from Kathy. I will be taking you also in here. You might be muted yourself.

Already looks like you are completely unmuted. Feel free to ask your question.

Kathy Stevens: So I was wondering, all the industries that were here earlier when, did they did they move someplace else or did they just become obsolete?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: So that's my mom. Hi, mom. It's time. Yeah. That's a great one. I know I didn't set her up for that. I swear. No, that's that's a really good question. So there's a little bit of both. One of the things that I want to study and which, we, we haven't gotten around to doing it, and Doug actually was, maybe sometime in the future, maybe he'll come back and help me. Or maybe I'll have to get some other GIS student to help me out. But one of the things I really want to do is map what happened because, my, I know that at least anecdotally, many of these factories moved out to Canyon County.

And so there is a, you know, as you can imagine, this research gets very involved and very complicated because we're talking, about rural urban divide. Then to and also some issues of racial and environmental justice by those sorts of big picture movements. But as you know, many factories are still out in Canyon County.

And, so some of them moved, and then some of them shut down, the Ford assembly plant, for instance, that was here for a short period of time. You know, they they consolidated and they, they went to places that were bigger and had, had a bigger demand for cars. So that wasn't so hard to shift from.

So, you know, it varied. But that's actually one of the things in the future. I saw Jennifer Holley asked, about new projects. But I'm thinking about voicing. That's one of the directions I want this to go is some spatial visualization of where some of these specific factories and companies ended up going. And I'm hoping to get a second grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help me with, some of these, these second phases of, of the research.

Doug Exton: Awesome. Thank you for that question, Kathy. And I would like to let you know, Doctor Stevens, that I would love to work with you more, and I would be happy to do some mapping work for you. We do also have a question again from Amy. How do you repair and rates, like I said, that correctly fit in with agricultural present and future.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: So, that is a complicated question. And I will answer it. I will try to answer it very simply, which is we are a state that, uses what's called appropriate of rights. So a property of rights appropriate to have rights is how you say it's lower. Our to keep it very simple. It's first and time first and right.

So if you live adjacent to a river, you you may have some right to it, but the prime right is whoever use the water first. So, basically with, agrarian and agricultural past and present, water rights are determined by who use them first. So, for instance, the Boise project has a massive water rights. They filed back in when they created the project, and I think it was 1906, if I'm not mistaken, they filed with the state engineer for, water, right to water.

I can't remember what the acreage was. 100 plus thousand acres of land, at a certain water, rate. So probably three acre feet per acre. And, so nobody can take that water away. It doesn't matter if you live adjacent to it. If, somebody has filed for all that water and there's, like, right now there are no there is no water in the Boise River to file on, which is hard to believe.

But it's pretty much totally over appropriated. And so even though you watch it flow by, you actually don't have the right if you live next to it to take water out, because all that water has been, filed upon in the past and you're too late. So, yeah, riparian rights are, not not not very, very useful here in Boise and in Idaho.

Doug Exton: And then I know you touched on this briefly, but are there any new projects you were working on or thinking about in Boise?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: This one is taking a lot of my time. You know, I don't I don't work as a professor full time. And so this is, this is what I get to work on when I'm not doing my other project work, my client work. So, this is kind of the big one, and I still have, there's a really important racial aspect to this, to this project as well.

As well as the labor aspect that somebody asked about earlier. And so between kind of continuing down that, the racial aspect of this as well as and when I mean what I mean by that is I think that there is a really important component of constructing white what's called constructor whiteness, in this story. And why why have we adopted this green identity?

And how does that play into our dominantly and predominantly white community that we have? And so, between that and the and the labor unions, those are sort of still outstanding parts of this project that need to get done. So, there's still you know, this project is still ongoing.

Doug Exton: We have another question, and this might be our last. It's, I grew up in Cleveland, Ohio area. The area became the Rust Belt in the late 60s and 70s, partly as a lot of heavy industry losing to other countries with cheap labor, especially in Asia. Don't you think? Boise's deindustrialization was also part of that process?

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: Gary, I did not know you were from Cleveland, and I'm going to blow your mind by telling you that I love Cleveland, Ohio. I have like and my students know that I'm sort of obsessed with Cleveland and Pittsburgh. But, yeah, I think you're I think you're absolutely right. There's no doubt about it, that globalization, plays an important role in this.

And, again, it's just sort of another aspect of this story that, you know, I haven't delved into and I may not I mean, other than, in sort of passing reference to, to to recognize that that is an important part of the story. But otherwise I'll die before I actually finish this. So I think I need to draw the line somewhere.

Doug Exton: Alrighty.

So it looks like that might have been our last question for the night. I just want to say thank you again for doing this. All of us obviously are very grateful. Thank you to everyone signing off. Once you sign off, there should be a survey that pops up from SurveyMonkey. We would love all the feedback so we can improve our programs.

Since this was just the first time that we've done it, and we would love to have many more. We already have some more in the works, so stay tuned for that. And yeah, thank you so much for everyone that and do. And again, thank you, Doctor Stevens for helping us with our first ever installment.

Dr. Jennifer Stevens: It was great. Thank you so much for having me. And thanks for all the great questions. Good night. You guys take care. Stay safe.