Dr. Rebecca Scofield

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

Doug Exton: This program is brought to you by the Idaho Humanities Council and supported with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Dr. Rebecca Scofield: Hello, everyone. Welcome. My name is Rebecca Scofield. I am an American historian. I focus particularly on the history of gender and sexuality in the US West. And today I'm here to talk to you about how historians do our job, how, we both find evidence and then create a structure and a narrative with that evidence and why sometimes it is hard, to capture marginalized stories, because of the ways in which we have collected, preserved, and, and written history.

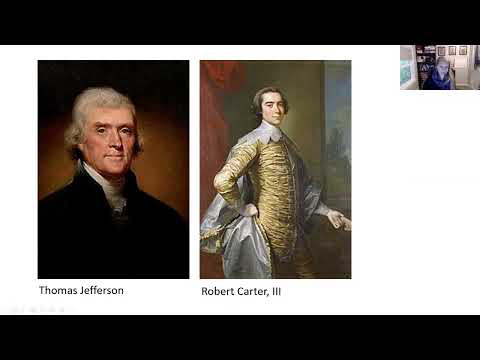

So I, I'm going to go ahead and share a PowerPoint with you. We're really asking today how history is produced, how that production process creates specific silences. And I'm really asking within our sort of cultural context now, which people are talking about revisionist history, can history actually be revised? So I think we're all familiar with Thomas Jefferson. he's one of the people we refer to as a founding father.

He was a lawyer, philosopher. he very famously wrote the Declaration of Independence, served as secretary of state, vice president. He was also a plantation owner. he owned 600 enslaved people and infamously, had a relationship with, an enslaved woman. He owned Sally Hemings. and this relationship started when she was about 14, and he was 44.

And, he would father six children with her. This, is someone we are all familiar with. We all learn about Thomas Jefferson in our classrooms, as children in this country, and to some degree, when we're young, we learn about the sort of positive side. And it's not until we're older that maybe we're introduced to some of, the messier parts of Thomas Jefferson's life, which, of course, we all have messy parts of our lives.

Now, you may be familiar with this person, but you also may not be. So I'd like to introduce you to Robert Carter, the third. He was, slightly bit older than Thomas Jefferson. He was born in 1728 and died in 1804. But they were contemporaries in many ways. Like Jefferson. He was a lawyer. he was a, plantation owner in the Northern Neck of Virginia.

in what would become the United States. And for two, decades, he sat on the colonial Virginia Governor's Council. Now, after the American Revolutionary War, Robert Carter, the third, converted to, Baptist faith. This was actually still illegal at the time. as, the Anglican church was still seen as the official, church, in the early years of the Republic.

Now, based on his religious experiences, Robert Carter the third, began interacting more, as his church welcomed in, enslaved and free black people to worship alongside, Anglo Americans. And based on these religious experiences, he rejected, slavery and started to search for ways to, man, you met or, free his enslaved people. Now his own, great grandfather had freed enslaved people in his will, but his grandfather and his father were prohibited from doing so, both by Virginian law and their own greed.

So, Robert Carter the third really hoped that Virginia, like New York, would pass, a, a, law after the revolution that would free enslaved people. He was very disappointed that they did not. however, after that disappointment, he, created what was known as, the deed of gift, in which, he freed about 500 people.

He not only freed them, but he offered them wages to work on his plantation and often granted them parcels of land, which they and their families had been farming, for generations. This unfortunately enraged his white neighbors, his white tenants and his own family. Carter and his daughters were forced to flee, their home, under threat of violence.

and he would not return until his burial, to as as soon as he was buried, his son brought his his body home, buried him, and immediately the next day, purchased enslaved people for the plantation, thereby obliterating, Robert Carter the Third's legacy and, all of the work he had done to uphold the standards of equality.

So here we have somebody who talked about equality quite a bit and wrote very eloquently and compellingly and helped create some of the foundational documents of our nation, but often in his personal life failed to live up to those ideals. On the other hand, Robert Carter, the third, was not a prolific writer, however, he in many ways walked the walk.

He, tried everything in his power to ensure that people were valued as full humans. but only one of these stories are taught with regularity in our schools. And I think, partly that is to do with documentation and also how, we like to narrate the American past. I think that there is room for both of these stories.

and I think that it is, part of learning and growing that we include, these, narratives that push back on the idea that none of the founding fathers, opposed slavery or that people were just a product of their time. Times produced many people. So how and how do historians do their job? What do we really look at?

Well, today I'm just going to introduce, two main concepts. What that is the first, of course, evidence history, like all scholarly study, is grounded, in facts. So where do we find this evidence? This can be written documents or, material culture such as, pots and furniture and, homesteads. These could be newspaper articles, photographs or paintings, government records.

there's also, of course, oral histories, family stories, local law, the way in which people have always, had oral traditions and passed down stories of the past to their children. And then, of course, we have things like newer technology, like DNA testing. of course, there was widespread suspicion, or local law about Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson's relationships.

However, that evidence was confirmed in the 1990s through DNA testing, that demonstrate, Thomas Jefferson was indeed the father of Sally Hemings children. Now, this is the raw material, right? Historians go out and find all this material, and then we have to give it structure. We have to tell the story and that comes with very specific ideas.

Right. historians tell of the story of, the past based on their own perspective in a lot of ways. And, the theories within there that they're working within. So we'll talk about that a little bit more. But also kind of fundamentally the structure of history in any, culture asks whose stories are important. How do we tell them, how do we find them?

How do we preserve them? and and who has been, sort of deemed worthy for, print. So let's dive into this a little bit more deeply. specifically, I want to talk about how in the creation of bodies of evidence, very specific stories get silenced at each stage. So first of all, we have archives, right?

This is where historians do their job. We go into archives and we look at, materials that have been collected. Now collecting itself, dates back to the enlightenment, when Western powers were interested in going into other countries. and a lot of people would say looting, things like writings and statues and masks and, all sorts of cultural artifacts, that they could, bring back to Western countries, display, name, collect, and, and really, dictate the narrative around.

So already when we're looking at collecting practices, we're in an extractive, mentality that certain people have the right to go in and take things from communities, and put them in the basement of museums and libraries. so these collections became the basis of the historical profession as we know it today. Now, this is very important because, as these collection processes became standardized over the 19th and 20th century, we had to have a way to find things within the archives.

This usually happened, not things were not named for the peoples who artifacts they were or whose writings they were, who images they were, but instead, collections were named for the person, the scholar or the archeologist or the oral historian who had done the collecting. And this is very difficult, then, for communities to ever find and, their history within the archives, because you cannot go in and search for your grandmother's name.

you have to know who the scholar was that collected her oral history or took her photograph. and so, we can see this here in this image. it just says employees of City Meat Market, Wallace, Idaho. And this is part of the, Barnard Stockbridge photograph collection at the University of Idaho. So, again, it's the photographers who are remembered, not the actual people.

So it would be very difficult for somebodies descendant to locate them in this archive. And it's very difficult for historians to tell, the stories of these individuals, because they go unnamed in this photograph. And again, this naming practice, ultimately points at, at who was worthy to donate to collection, who, did the archival, institution.

So whether that's a university or a museum or a library, who did they deem worthy, to donate and and whose name to place on that? And this is also grounded in the notion of, provenance, credibility and space. So provenance is a an idea of, proof, right, that you need to have information regarding the origins, the custody of, and the ownership of an item.

so this often means, places will, will recognize official records like acquisition records or purchase records, but most people, don't keep those things. most communities have not, found it necessary to, prove the the custody chain of any given item. And it also, then sort of creates a hierarchy in which things like stories, memories, oral history, a scarred kitchen table or a grandmother's quilt, those things lose value, because they don't have prestigious, custody chains.

Right? Famous people did. Not on them, even though they tell amazing stories of everyday life. And again, this gets back to credibility, whose, stories were credible, who, was, seen to have a legitimate story. So, for instance, we can and look at the, letters of Jane Franklin, who was Benjamin Franklin's sister. They had a lifelong correspondence, and yet we don't have a letter in Jane's voice until her 40s.

because archivists threw them out. They weren't deemed, important enough to take up space. And space is incredibly important in, archival collections, because institutions only have so, so much space, so much money to create space, and really only so much, ability to make these spaces secure, have them at the correct temperatures, have them, stored in proper boxes, all of these things that, allow us to preserve documents that, you know, literally crumble because of, of their fragility.

who gets deemed worthy of that space is a very contentious process. And, often you will just have a, employee, we read through collections and decide what documents are important or not. and again, that comes with a lot of cultural assumptions about whose voice matters. It also depends on the type of institution you're working with.

Right. if it's a university, a museum, corporate archives exist for instance. But corporate archives might not be interested in retaining documentation that makes them look bad, that demonstrates they may have polluted, or that they stripped, people of their rights in removing them from land. all sorts of, either a lack of preservation or poor preservation, tactics can be utilized to make sure that only positive stories are able to be told.

So, lastly, a very crucial collecting, process that sort of narrates whose stories are available, and how they are told is, processes of categorization. So, for instance, we can look at the US Library of Congress subjects headings. so these were created in the late 19th century, I think around 1895, to help, give some kind of organizational structure to this massive collection of writings.

However, the subject headings also illustrate whose stories, are deemed history versus folklore. and the use of categorization headings often means if you go in and do a word search to try to find documents on your community, to find writings on your community, they will not be under, literature or history. They might be, under something you would never assume, something like folklore or mythology.

So the subject headings, help dictate how we understand history. whose stories are, deemed, legitimate in a lot of ways, and whose stories are accessible so with all of these steps to get evidence to historians or to the wider public, you can see the ways in which, specific silences could happen, right? If you are a formerly enslaved person, how would your items be collective?

Would they have been collected at all? how could anyone uncover you in the historical record? if your name was not recorded, if your name was changed in the Middle Passage when you arrived in the United States and you were given a name that you were not given at birth, if you didn't know how to read or write and you did not have diaries or letters, or even if you had diaries and letters, and a specific archivist decided that they were not, interesting enough to keep and threw them away.

If your grandmother's quilt was deemed unimportant or too bulky or too hard to preserve, if a book that was written about your community, was labeled folklore and not, history, how would we find these people in the, in the archive? And the reality is, is that for the past several decades, historians have been finding ways, to recover people in the historical record, to recover their stories.

But it has taken a great deal of work and has often been labeled revisionist. instead of just seeing it as, being more creative and how we can find these voices buried in the historical record. So then I also want to touch on, how historians tell these stories. So we've talked about the barriers that are in place in the collection and creation of, of historical, evidence.

But let's think about how then, once you have this evidence, how do historians deploy it? So the first thing to remember is that there was not ever a time in which history did not have a perspective. History has always come through people, and people always carry with them their own perspectives built on their life experiences and and their worldview.

So it it is just a simple fact that everyone carries some biases. and that is okay. as long as we are able to talk about those biases, to understand them, and to be upfront about how that shapes our work, how that motivates us, and, and how that, sort of helps us interpret evidence and tell a specific story.

So, I would really encourage you to be, cautious about ever thinking, any history that you've read, in any setting isn't, in some way, shaped by a specific perspective. Now, much of this, as I've said before, is grounded in our worldview, whether that's our philosophical understandings, our religion. our, sort of idealized gender, perspectives, all of those things that we carry with us, inside of us, help shape our work, help shape how we tell that story.

So this doesn't mean that just because you have a worldview, which we all do, that doesn't mean you can't be objective. And that is what I would, emphasize here today is looking at how, historians can take evidence, can objectively interpret it, even though they carry some worldview. It doesn't mean that that worldview, is manipulating the evidence in any way.

And then for academics, right. This comes, to with some academic training and theory. Now, most historians will be pretty upfront about the theories that are helping shape their story. What what are the questions they are interested in? Right. are they coming from a post-modernist perspective? or a feminist perspective? Most historians will be operating in multiple, theoretical backgrounds.

And this is sort of less important for, you to really understand on a, on a deep level. But it is there and, and you can usually uncover a historian's, academic theoretical perspective, in the introductions of their books, and really understand how those theories are just that they are theories. There are things that are being tested out.

they are not, accepted as fact, but they do help shape how, how we tell stories. And then, of course, historians, like most scholars, are also storytellers. they make narrative choices whose voice is going to be the most compelling, whose perspectives should this be told from? what details are necessary to evoke, the past world for readers?

and which details are simply, just noise and not that important. And sometimes in making those narrative choices, we uphold racial hierarchies. We, create, resist, or re entrench a gender ideals. all sorts of, cultural work is done through historians narrative choices. So again, please be attentive to that when you're consuming, any form of history, whether that's in a museum exhibit, or a popular, historical fiction book, what are the narrative choices being made, by authors?

And does that effectively silence other people, or does it, allow specific voices to, to speak through? So, as you go out into the world, as you maybe help students in the classroom, think about history. Remember these two, aspects that, yes, they're working with raw evidence that is often hard to uncover, but also they're making structural choices.

They're telling a story in a specific way. that is very hard. And often you'll see, scholars or authors change over time, as they hone their craft. So this brings us to our last question of what is revision? Can we have a revisionist history? I would make three arguments that are listed here on the screen. I would say we can't change the past.

We we cannot literally make up facts, but we can change who is included in our stories. We can have more expansive histories. This does not revise history. History already happened. You can't change it, but you can change your understanding of it. And I think it's really important to remember that you won't agree with every history you read, because people come with perspectives.

So you might disagree with their interpretation of evidence. But what question you really need to be asking is, is their research sound? Did they find the right evidence? Are there things they should have referenced? Are there aspects of the story that go untold? really focus in on those types of questions about evidence? If the evidence is sound, then it's fine to simply disagree with how somebody interprets or understands that evidence.

and you can still use their work as a, jumping off point for your own understandings of specific things, specific people or time periods or events. but always look to that evidence and then also remembering that we can't all agree on history, agreement. it's sort of a, a cop out, disagreement is is part of scholarly life.

It's how we move forward. If we didn't disagree, then we're stagnant. and, that, you know, seeing disagreement as a healthy and normal part of scholarly life, it's how we push our understandings. It's how, we, look to the past to to really think through our future. so I would hope that, you all embrace that, sort of mandate of of debate and disagreement and see it as a normal part of scholarly life.

We should be presenting our students with as much evidence and information as possible and helping them build the tools to interpret that, in an analytical and critical way. So thank you very much for your time today. please feel free to contact me with any questions. I will have a second, connected conversation that sort of, puts, some of this into practice and, delves into, how can we tell messy histories, in a way that, acknowledges everybody's, experience and perspective.

Thank you again for your time.