Raffi Andonian

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

Doug Exton: This program is funded through a more Perfect Union initiative of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

All right. With me today is Raffi Andonian, celebrity historian to explore the American Dream.

Raffi Andonian: All right, well, thank you to Idaho Humanities Council for doing this. I'm very excited to be here and to talk about the American dream across time. I am a celebrity historian. I have a history in the National Park Service, as you can see there in the photo of me years ago on a Civil War battlefield working. And of course, we have fought over the American dream so often, both bloody and not bloody, and including on these battlefields or sometimes in protests.

So we're going to walk through a few centuries of seeing how the American dream came to be and what we're fighting over, and how it's contested. Looking back to 1607, what many consider the beginnings of the pre United States. Now, of course, in 1607 there was no United States. But this is the first permanent English colony which is Jamestown, Virginia.

And it started with the Virginia Company. The Virginia Company was a corporation. And that corporation had a royal charter with King James supporting it. But the corporation had investors that funded this colony to go across the Atlantic Ocean from England to the North American mainland and try to make a profit by bringing back resources, much like you would in a colony, to then, produce and manufacture in England.

Now, what's fascinating here is a couple of things in why you think of the beginnings of the American dream here. One is that you have this public private partnership, right? You have the king, the crown, and a corporation working together on this venture, hoping to make money. And two is once the folks that are here in Virginia or in Virginia, when I say here, here in North America, but particularly in Virginia, which you see some scenes of here with the James River, up in the upper left and a monument to John Smith, who we all know in the middle and on the right you see an archeological site that is still remaining from the

era in Jamestown, Virginia, today. But when the people were here, the Englishmen, they had a hard time surviving for several years. They needed the help of the local American Indian groups to get by the difficult winters and food supply, and just knowing the landscape and the environment around them, as well as diplomatically, because there are different groups that are not always friendly.

And so in that context, they first had to help of the indigenous people, but later eventually would no longer have that as they would continue to build rivalries and perhaps not exactly have great relations. Right between American Indian groups and Englishmen. But down south in Virginia is not the only place that this was happening. While in Virginia, it was a profit motive up in New England, particularly in Massachusetts, it was more idealistic, not so much the corporation, not so much about men, not so much about finding raw materials, but creating an idealistic society.

And here is where we often would look to for ideals of the United States. When we look backward on the left is John Winthrop. He gave a famous sermon in 1630, early in Massachusetts lifespan, that they that the United States, or what we consider United States today, but Massachusetts, particularly for him, this region would be seen as a city on a hill, a shining beacon in the darkness.

And you would later hear, for example, President Ronald Reagan referred to a city on a hill in the 1980s. So this still has staying power with us today. When we look toward what the United States has to offer, not just the economic opportunity that we see in Virginia, but the ideals of religious freedom and idealistic society where groups fit together.

Family structure a lot of these ideas come from the Puritans in Massachusetts in this period. Now go 100 years later in the same place in Massachusetts in 1749, you have Jonathan Edwards. He gives a sermon also. Now his sermon is called one of his many sermons. The famous one is called sinners in the hands of an Angry God.

And this is one of the key pieces of literature and, oratory that gives fire to what is now called the Great Awakening, which is a big religious fervor, a movement that takes place across, the North American English colonies in the mid-18th century. And in the process of doing so, there is this idea that while you might sin in the hands of an angry God, there is an opportunity for redemption and opportunity to redeem yourself and to improve and to be saved again.

And these principles, to me, serve into the American dream later, because we often think of the United States as a place where you get renewal, a place where you can lead back the sins or the bad things, or the bad positions of the old world, and come back to the United States and visualize and dream all these things that we're seeing where there the economic opportunity that Virginia saw, whether it's a shining city on a hill, the land of opportunity that John Winthrop saw and for Jonathan Edwards, the opportunity to redeem yourself, to leave back your sins and to renew and rebirth as an American.

Now, these ideas, just a few decades under on the tail end of the Great Awakening, come together in the American Revolution. Now we all know Thomas Jefferson and the 4th July and the declaration independence, but there is some different origins there, and we can trace it in all kinds of places, but specifically in Virginia, going back, remember where the Virginia Company started there a century and a half prior?

There is something called the Virginia Virginia Declaration of Rights. And now that Declaration of Rights was passed in the Virginia Convention, right there in that building, right in that building, which is the Capitol building in Williamsburg, Virginia, which is still there today. And the person who was the primary drafter for it was George Mason. What did you see pictured there?

That was issues, rights use language like talking about life, liberty, happiness, property. These are all things, concepts and words that would later be used by Jefferson in a variety of writings, of course, but especially in the Declaration of Independence. This is done just months prior to what? Later to later? to do, I should say months prior to the Declaration of Independence.

So of course, people at this point don't know the declaration had been coming. But later, with this fresh on their minds, this is what Jefferson is thinking about, among other things, to write what he does in there. For the first time in our conversation here, we see the birth and the notion of the United States. Remember, there was no United States in the prior examples.

But later on, when the United States comes about as a country, it leans on those ideas. It draws its history and identity backward to draw upon those stories, to help form its identity as a new nation. Because this part of how you get legitimacy as a country is to create some kind of common identity. But of course, in this process, not everyone was participating equally at the same time that you have these declarations of rights and these ideals, you have, of course, American slavery in what is now the United States.

By the 1770s. And that, of course, is one of the big contentions that comes into play for decades to come in the young country in the younger United States, not only limited to the South, where slavery existed as an institution, but including in New England, where they profited from the slave trade, trading across the Atlantic Ocean, so and not participating equally.

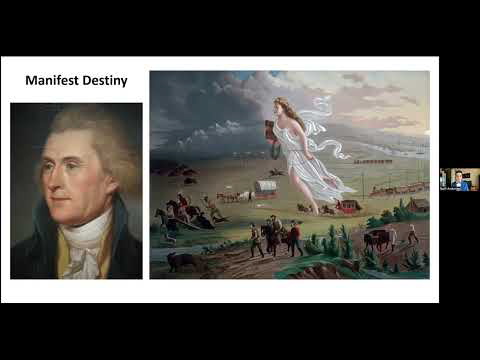

One way that we can look at this is manifest Destiny, as it was known, manifest Destiny as the term implies, is that it was obvious. It was clear it was manifest that the United States was destined to cross across North America. The continent, from sea to shining sea, from the east coast, and eventually to the west coast. That was obvious to the proponents of this ideology.

Thomas Jefferson on the left there, famous for the Louisiana Purchase, among other things. Right? The person who wrote the Declaration of Independence was visualizing a land of independent yeoman farmers. Yeoman farmers are middle class farmers, independent property owners, which, if you think about it to this day, we have that ideal. Right. And what happens when somebody comes out of school, they should, you know, come out of school and buy a house or get married and buy a house, right?

We still identify buying a house and maybe the white picket fence with the American dream. And so that notion of owning your little piece of property, your little piece of land still exists with us today. Now, in the process of doing so, however, manifest Destiny is tied to groups that were not participating in it. Look at the painting on the right side.

They're very famous in the 1840s, circulating across the United States, depicting manifest Destiny, depicting Lady Liberty over there, depicted as a white angelic woman that is crossing the continent across the savages as they saw that were on the landscape, bringing civilization to the wild. Because we saw the West as wild, which we still to some extent do despite all the long history that is there of people not only from the Spanish colonial days of European descent, but of course, well before any Europeans had ever come to North America in the process of expansion.

Intertwined with that was not only some kind of exclusion, if you will, of American Indian groups across the West and of Mexican and other Hispanic groups that were in that region, but also to exclude black Americans because there was a fight that eventually led to a civil war with a series of compromises. For example, the Missouri Compromise in 1820, or the compromise of 1850 or later on the Kansas-Nebraska act in 1854.

All of these are pieces of legislation. The United States Congress, that are fought over by slave states and free states. That it states that support had slavery, and states that did not have slavery, that wanted their interests to expand out West. And these fights over whether the newest state and the latest state that is coming into the Union from the West should have slavery or not, were part of what eventually led to the Americans Civil War, so tied with this American dream of visualizing the opportunity that we see, both economic and idealistic, both of the farm and a civilization that we thought we were getting across from the East Coast.

If you are a English descendent or white American from the East Coast, tied with these is the exclusion and eventually the war. And so now, during the Civil War in the 1860s, shortly after that period of the big manifest destiny mentality, you have, of course, the battle of Gettysburg, one of the defining battles of the Civil War. Civil war, of course, is for four years.

And there's two main objectives. First, of course, to preserve the Union as the southern states that formed a Confederacy had left the United States, but they had done so because they wanted to protect their interests in slavery, because they did not think that Abraham Lincoln or others in the North were willing enough to protect slavery, enough. And Lincoln and the beginning of the war did not always see slavery as an important cause to in during the process of the war.

However, during the war, he comes around and says, you know, we need to get to a root cause of this, in part because of Frederick Douglass being on his ear saying, you know, we should preserve the Union without ending slavery. You're going to have the same problem again in the future. So they add the objective of ending slavery to settle this and get this done.

So they don't have to deal with this again. Well, one of the big places that Lincoln helps announce this shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation that is legally trying to declare slaves free. What happens is he speaks at the Gettysburg Address after the Battle of Gettysburg just a few months later, when they established the National Cemetery, which you see images of right here on the screen and then upper right.

What I particularly enjoy showing here that I appreciate is this is the graves of the unknown soldiers, because those graves are so small, because they're numbered. They do not have names. Men who sacrifice their identities in order to give what Lincoln called his Gettysburg Address the last full measure of devotion. But also in his Gettysburg Address, he refers to unfinished work.

The unfinished work he refers to is what he would call the new birth of freedom, right? In his Gettysburg Address. So what you see here is a civil war becomes this moment, this moment of thinking about who we are as a country and defining and redefining the American dream, the unfinished work that she saw that the country had to get that new birth of freedom.

And you notice that the new birth of freedom sounds a lot like the man who gave the sermon, the sermon for sinners in the hands of an angry God with, of course, Jonathan Edwards talking about that opportunity for redemption. These ideas and these mindsets permeated would be the bedrock of how we thought about ourselves. Despite being decades or sometimes centuries apart.

One way I feel connected to this is with this pen right here. This is a pen made of the wood of a witness tree. A tree that is that witness that was next to Abraham Lincoln when he gave the Gettysburg Address. And to me, this is a very direct connection to that moment to understand that we still carry with us today this notion and fighting about the American dream and fighting what that new birth of freedom means, and debating what exactly these issues and how they should unfold, whether economically, ideologically, in our identity and even our history.

And this pen was right there to hear Lincoln say those words, not as a pen, as a tree at the time, but now in the form of a pen that I keep with me for my time. Having worked at the battlefield of Gettysburg and having led thousands of visitors across that very cemetery. Now the military is an important place where these things play out almost a century out of after the Civil War and after.

Now we had a constitution that was reworked because of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments that ended slavery. protected equal rights and equal access and of course, provided voting rights of meaning that they, prohibited discrimination based on race that was still only for men, not including women, but at least what happened in the process here is they tried to again uproot the causes of the Civil war, eliminate race based discrimination, at least legally.

But it wasn't. Over almost 100 years later, these issues were still going on. And the reason I point out Harry Truman and World War Two is you see the images of a Second World War and Harry Truman himself here is because people often forget that in the Second World War, as we fought as an army of liberty, an army that brought liberation to the world from oppression, from Hitler, and of course, ending the war in the Pacific theater with the atomic bomb, justifying it because we were bringing our ideals and of course, eventually build allies with both Germany and Japan that we have to this day with the alliances.

But we did that. The Army of the Liberation as segregated soldiers. Most people forget that the soldiers who fought in World War Two were segregated in white units and black units. That was common. That had been true since the civil War, when black soldiers were first allowed to enlist. And we had done that for all the wars since for almost a century, because we believed that black soldiers would not as capable of as white soldiers.

But Harry Truman in 1948, with an executive order putting together a committee, ended that. And so it's only relatively recently in the context of history, when you consider that we had more decades of and more wars fighting with segregated soldiers than we have with integrated Army military units and Harry Truman address that, helping bring, if you will, access to the American dream through the military.

And the reason I say access to the military American dream for the military. It's because many soldiers who fought, who were not white often did so to prove their patriotism, to prove that they too are full Americans, that they too are willing to commit and risk that sacrifice. And in recognition of that, Truman understood that and had this executive order.

So the military is very much intertwined with notions of civil rights and participating equally in the American Dream. And so, speaking of participating equally in the American Dream, that leads us to the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King, I have his life span there because his life, of course, was cut short. He could still be alive today at the age of he would be 93 years old, younger than my grandmother.

And Martin Luther King, of course, is that him by himself and doing this movement, you can see, you know, many people there on the Washington Mall. And of course, he was not the only leader, but we see him as the face of the civil rights movement. It's no surprise that the civil rights movement took place in the aftermath of World War two, because many soldiers as big as World War Two was.

Many soldiers came home and they thought, well, why did I serve my country? And I'm treated as a second class citizen here. Remember, we still had Jim Crow segregation through and after the end of World War Two. It's not until Brown versus Board of Education, the Supreme Court decides in 1954 that legally ends segregation. Although take another 20 years to actually implement some of those laws.

So you think about it. Yes. We may have integrated the military shortly after World War two, but society on the home front was still segregated to some soldiers and veterans in this case would come home and recognize that. And that ignited a certain passion and a certain movement to say, well, maybe we should do something about this. And many people came to the fore.

But Martin Luther King, being one of the big figureheads that we remember today, and on the left there is a home that he grew up in. Another site that I used to work as a park ranger, as I did for the Civil War, and now here at the Civil rights, at a civil rights site right in downtown Atlanta.

The home of Martin Luther King. As a child. I don't work there anymore. But what it did to me is it reminded me that how I was dealing with some of the same issues that I had seen from events that took place a century prior, historically, and a moment that I remember most transcends even people here in the United States.

I was standing there on that porch that you see with the door and the staircase, and I was leading a group of kids with a chaperon, kids between age nine and 13, scarred, some of them lashes on the neck. One of them had the skull pushed in. Clearly, these kids had been through a lot and they didn't really speak English.

In speaking to the chaperon, as I was on that porch walking up the stairs, a chaperon revealed to me that these kids were slaves. Escaped slaves. This is in 2010, escaped slaves in 2010, aged 9 to 13. So let's call it born around a year 2000 plus or minus. Their escape from the illegal human trafficking trade in Haiti and only recently come to the United States through this program that the chaperon helped lead, and this site that they said they wanted to see was the home of Martin Luther King.

To me, it was such a powerful example of two things. First, the power of place. They wanted to see the place to be there, to feel connected, as I did with this pen. And when I was at the National Cemetery at Gettysburg. But to the power of the American dream, to figure, like Martin Luther King, to transcend just those of us that live in the United States, to be global and across time.

Because remember, Martin the King was killed in 1968. These kids were born 30 plus years later and were in front of me, 40 plus years after Martin Luther King had been killed. And yet this legacy meant something. The American dream to them meant something. The land of opportunity. The image of it meant something to them, and they connected to it through history.

More recently, when we look across these issues that we deal with, one way we think about the American dream and access to it is on our currency. What you see there is myself doing a TV program on a CBS station and the American Women Quarters program that is by the US mint, ongoing from 2022 to 2025, is the first year, 2022 that they did it, that is, that they have five women a year honored for four years.

So that is 20 women across the four years, five times four on the back of the quarter. And I brought this with me here today. You can see the quarters right here, that same prop that you see that is on the TV screen. These are the five women currently in 2022. And you can see that these five women who you can pull up if you just Google us, mint, American Women's Quarter Quarters program, you will find it.

Just make sure going to the US myGov website. So you're going to read to their website. And of course on the other side is George Washington. As you see here, and expand it on the screen, as I gave one example with Maya Angelou, who's one of the women who is honored. Now, I want to emphasize this. These are not commemorative coins.

They're not silver. They're not collector's items like my collecting, but they're not being made just for collecting. They are circulating in our pockets. You can go to your bank and ask for it. You can buy rolls of the quarter quarters from the US mint because currency money is used. Nations honor the heroes and it literally carries value because it's worth something and we carry it in our pockets.

And what you see on screen there is on par with George Washington, of course, another American hero, perhaps the American hero. And the other side is Maya Angelou, a poet, social activist of the 20th century, one of the most famous and transcendent folks to talk about and bring attention to so many social issues, both in Martin King's era all the way into the 2000, when she won multiple national awards, recognition from the United States presidents, multiple US presidents, speaking at Bill Clinton's inauguration, making history, being awarded a National Medal, National Medal of Freedom from President Obama.

What's interesting here to me is that it shows you that there are two sides to a coin, that there are multiple ways to look at the American dream. There are multiple access points, multiple people to consider, and different groups and experiences, whether it's that of George Washington and the leaders and the founders that established these ideals, codify them into laws for us to follow, for us to build upon, for us to take for granted and assume that everyone else did, which they didn't at the time, but also have the heroes that come in like Maya Angelou and others more recently who help tell us to complete the picture, complete the ideals that were in the

Virginia Declaration, independence, complete the ideals that Thomas Jefferson wrote about. Complete the ideals that if we go before United States, folks like John Edwards and John Winthrop, we're talking about that new birth that both Edwards and later, Abraham Lincoln, the new birth of freedom, referred to while still providing an economic opportunity for everyone. As we saw with Jamestown, having that economic opportunity be a key part, because remember, at the time, England was a poor nation.

So whether we're looking at the colonial era, looking at the revolution, looking at the expansion West, the Civil War, the Second World War, the Army of Liberation, the civil rights, and today, with the money in our pocket, we see these themes of the American Dream being defined, redefined from any. My thought process. And of course, having folks raise the questions of who gets to participate.

I want to cover these issues a lot, and you can find me in doing so on television, but also for free, both on my own TV show and local TV stations. If you check out the YouTube channel Celebrity History, and you see a lot of my content posted there with my appearances across the country or any of the websites you see down the middle there, more about me at Rothesay and Domain.com.

Or if you want to watch my TV show where I deal with some of these issues in the present day with interviews of live people. Today you can go to the museum slash watch free access as well, or celebrity historian.com to find more of the variety of things I put together to help us discuss how we remember historic sites and how history tells the stories of the American Dream and who gets to participate.

And so with that, we'll bring this tie to a conclusion, to tie together and understand that across the centuries, we've always been debating the meanings of the American dream. It is nothing new to do. So today it's been going on for centuries, and we'll continue on. And that's why in the United States we have such wonderful dialog on these issues.

Doug Exton: Wonderful. Thank you so much for the wonderful presentation. And, you know, the journey you took us through, you know, throughout the history of the US and the different people involved, but also the different perspectives, as you mentioned, with that one painting of manifest Destiny, who was it you know, serving and who was it hurting and who was being left out in that notion of the American dream in that time?

So one of the questions that I do have for you, what role do formal organizations such as museums and archives play in contributing to the belief of the American dream? And I know you spoke on how you've served your multiple various capacities, both at Gettysburg and also at Martin Luther King Junior's house.

Raffi Andonian: Yeah. I mean, I think that the museums and archives, I mean, are critical. I mean, for example, one of the documents I pulled up was the Virginia Declaration. Right. An image of the document. Right. That's from an archive. But museums tell these stories, right? Museums are artifacts. I pulled out a couple of these right here. And this, you know, to me, they're not exactly artifacts, but they are material things that connect us to the past.

Now, of course, to get actual artifacts. These things are a way to tell the story and convey and help people remember that, you know, these issues are ongoing, have been happening in the past. But also, I think people forget the power that museums have to construct a narrative. And I think museums need to take that very carefully, because what happens is, you know, if you have inaccuracies in there, it starts to become a problem because there's credibility to an institution.

Right? So we have to be very careful as institutions, whether we're doing programing or have artifacts or whatever it is, we're doing public facing stuff to make sure that, we're being accurate. But also, I think multi-layered. There are multiple perspectives that are correct. Right. And those perspectives all should be represented, both the George Washington and Maya Angelou.

Right. And so I think that museums and, and archives and public sites are critical to doing so, as you saw with the story, with the slaves that I met, you know, look how important the public site was to them in interacting with the American dream. Right? That is what makes it real. I love reading, I have 3000 books, but there is a difference between that which you need to do also, but making it come alive.

My interest in history came when I was a little kid in fifth grade, going to Philadelphia, seeing Constitution Hall and seeing the old rowhouses. To me, that made history come alive. I was a kid in California. I had no connections to the East Coast. My parents are immigrants. I have no connections to the American Revolution. From a family lineage standpoint, I'm the first generation born in the United States, but when I went to Philadelphia, history came alive for me.

And it's from that moment, obviously, that look what I have grown into, right? Having an interest in this and trying to do it for the public. So that's the power that these sites, museums and archives have been telling these stories, inspiring people and also making sure that we have degrees of accuracy with multiple perspectives.

Doug Exton: And how is nationalism and symbolism, you know, impacted the American dream as a concept? You know, I definitely think this, you know, circles right back to the painting. You show it as one of those examples. I was wondering if you can expand further and maybe talk about some other examples that have been really dominant throughout history. You know, like Uncle Sam, you know, the little Uncle Sam, once you poster stuff like that.

Raffi Andonian: Yeah. World War Two is very much, you know, has nationalism involved. Right. It's Western expansion, Cold War. Right. You think about the Cold War that I think needs its own treatment. Nationalism is a big part of the American dream. Think about, for example, in the context of the Cold War. In the Cold War, you had these this binary, right.

You have the stark contrast right, between the United States, which is the land of liberty. And of course, you know, the evil empire is where you call it with the USSR. Right? Doesn't end there. There's a series of, you know, engagements and all kinds of foreign operations that we as the United States are involved in because we're worried about the spread of communism.

Right. There's a domino theory, which was what, you know, is partly what leads to the war in Vietnam or some of our relations in Latin America for decades. So it's not just about Russia, right. And the Russian Empire, but really what I think is that in that process, you have a nationalism that's developing that says, look, our way in the United States is the right way.

And those that other way, the contrast is the wrong way. Right. And in that process, the very famous moment I remember is the kitchen debates. Now, I don't remember it personally. I was not around, but but you have U.S. President Nixon meeting with the leader of the USSR. And what's happening is, you know, in the USSR, in the Soviet Union, you have, I think it's like three choices for the for the, kitchen gadgets.

Right. And the kitchen appliances in the US, you have, you know, countless choices and one is saying you don't need that many choices and the other is saying no part of what freedom means that you have all those choices. So if you like. So that again is both ideology and economics, right. Like these things are connected like Virginia and Massachusetts in the colonial days because the ideology of freedom.

Right. Well, what if we the mean it means I can consume more, I can consume differently. Right? And I can have these gadgets in my kitchen. And that is what the kitchen debate symbolizes, this way of life argument. And there's a material part attached to that because there's prosperity. And you saw in the Virginia the Declaration of Rights, they're talking about life, liberty, pursuing happiness and property.

These things are connected, right. Or if I'm going to come out of school and buy a house, well, that's again property. We're talking about material things. This is always been part of the American dream. Right. And so the nationalism part to me is often used to contrast against other ways that are incorrect, whether it's the, perceived savages of the West who are one with nature and not civilized in the perspective of these folks, of course, to the to the fight we have, you know, with the Soviet Union in the Cold War, two, of course, ourselves being the Liberation Army in World War two with issues that were not directly connected to us, but eventually

kind of come into our scope, in part because of diplomatic alliances, because but you cannot separate diplomatic alliances and nationalism altogether. And that's part of the reason we come into the war later, this Second World War. We coming to it later compared to much of the rest of the world. So nationalism is intimately intertwined. And I finally had more recently.

When you look at presidential slogans, they're very much playing on nationalism. Right? And when you think about, you know, Donald Trump and you think about Make America Great Again, Make America Great Again is, of course, a reference to many things, but it is referring specifically to an image that is how that is being portrayed of making the United States great.

Again. That is some kind of you know, I think that's a, to me, an echo of the city on a hill, right. You're thinking about the shining moment that we had or and you want to bring it back. And what that means also, though, is nationalistic because it's an America first policy. Right. That's that's literally what he would say is America first.

So the nationalism and that opportunity are very much intertwined. It's not always in war, but also just in our rhetoric.

Doug Exton: In America has always kind of been described as, you know, a melting pot for various cultures as a way of kind of defining what American culture means, you know, just given the history being so unique compared to, you know, European countries or other countries across the world. but historically, when those various cultures, you know, enter the melting pot, they're not always represented in the national rhetoric or the national imagery, you know, because as you're saying, a lot of it's more of the, oh, if you were a white, not oh, if you were Irish or French or German or something like that, you kind of it forces that, you know, blending inherently.

So in your opinion, to that notion, kind of always go hand in hand with the American dream of, you know, pseudo forced assimilation of, you know, leaving all of your, you know, your heritage behind to become part of America and the American dream.

Raffi Andonian: I don't think it always goes hand in hand. I think it often does. I wouldn't I wouldn't use the word always. And the reason I say that is because it depends who you ask, right? Part of the what's interesting about the American Dream is I don't think we all agree on what the American dream is, right? We have this broad notion that we've been kind of touching on to, you know, prosperity, access, you know, these kinds of things.

But what does that mean? Right? Like, what does it mean to, you know, should we have equal opportunity or equal outcomes? Right? Is one of the things that we debate all the time. Right. So I think that depending on who you ask, there is more to some people are going to say, well, yeah, assimilation is part of, you know, the American dream.

That's how we come together. But others are going to say, no, well, this is diversity and there's multiculturalism that helps make the United States, I think, at different points, you know, both have some kind of perspective. As usual. The reality is some kind of complicated synthesis of all these. And it also depends on your perspective, your world, your experience and your community.

For example, my dad, who I mentioned is an immigrant, escaped from a communist regime in Romania. you know, he his family came here for opportunity because of the American dream. I mean, it's very personal for me. Right? And he started a business in that right away. But shortly after that was successful for decades. And that's how I grew in the middle.

I grew up in a middle class family. You ask him what that American dream means. I think it's going to mean something different to compared to, for example, a former sharecropper in Georgia who I remember would be was a janitor in the building I used to work at. In the conversations I had with him. versus you ask someone who maybe lives in New York City and comes from an affluent family like, say, the Roosevelt family came, you know what I mean?

So depending on who you ask, I think they're going to have different versions of the American dream and different desires for the level of assimilation or not. And I think that's part of the reason we go into these clashes sometimes because we don't always agree. So I wouldn't say always it's required. I think it depends on the perspective and the community you draw around you.

Right. Yeah. You know, where you live has something to do with that. The local community that you have. Are you an ethnic neighborhood? Are you not? You know, all these different perspectives really come in coming to play. Now, I will point out it's also fluid. So for example, you think about, Mexicans in California in the 1940s, Mexican Americans, but people of Mexican descent and sometimes, Mexican immigrants are being classified and all kinds of different ways in a period of like ten years.

There's a point where they're classified as white and they're classified as Mexican. They're classified as not white. And all these different classifications, all the people are the same people. All we're doing is moving the identification boundaries that we box people into according to our social categories. Right. So when I think of a segment when I hear the term assimilation and multiculturalism, I also think that it's not entirely up to you, but it's these kind of systems.

We have these social categorizations. We have that could make you assimilated or not, depending on how we classify you in a different in different circumstances. Right. So, so that I think that these situations are always fluid. And you know, there's think about the Irish you a much worse shape in the 19th century than they are in the 20th century as far as how they're accepted.

Right. How about Catholics, which is connected to why the Irish were not like that? The only reason, but there are other Catholics that are dislike like Italians and and German Catholics. Okay. what? You know, that's not so much an issue anymore, right? Being Catholic, although before it was. Right. So, you know, and it connects to the American dream because there was this notion that Catholics are, loyal to a foreign prince, which is the pope, that foreign prince is what the term a lot of founding generation use and that maybe made them so that their loyalties or, you know, questions.

So there's that nationalism part again. Right. And how how poorly can they participate in the American dream now? We don't think of it so much that way. It does. I feel like occasionally it rarely does pop up here and there, but it's of course not as prominent as it was. My point, though, is a fluidity. These things change across time as well, so I should.

I hesitate to use the term always, but all these things can be true at once.

Doug Exton: And this program is funded under the a more perfect Union initiative from the National Endowment for the Humanities, with the goal to help celebrate the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. How do you think the American Dream can be used moving forward to help create a more perfect union and bring, you know, again to that melting pot of our country, you know, together, rather than the way it's been sometimes used in the past of, you know, creating divides, whether intentionally or not.

Raffi Andonian: Yeah, absolutely. And it has been used to create divide, right? For many times, I think the way I mean, you know, it's funny, I think again at that quarter. Right. I think it's telling more inclusive stories. Right. Quarter now has, you know intentionally with the American Women Quarters program. both, you know, father of our country, George Washington, who I don't think we have to necessarily bash in order to make room for Maya Angelou and other historic women.

Both things can be true. And so I think the way forward is to play a game of addition, not subtraction, is to not necessarily, you know, say, well, we have to, you know, you win, I lose, or you lose, I win, right? It's not a zero sum game to me. We can just grow the pie. I think the stories are infinite.

you know, we have so many ways to tell these stories, so many ways to commemorate whether it's two sides of a quarter or many, many other ways. Right. So I would like to see for the American dream, you know, when we're thinking about it, to understand, number one, that everyone's American dream is a little bit different based on their position and their situation as I just described earlier, what my family situation and other family situations.

But number two, now that we have these perspectives on the American dream based on their experiences, their lived experiences are going to be different, right? Because you and I are to have different lived experiences, different geographies, different all kinds of things. Now, how do we make room in our public forums and discussions and dialog and symbols such as currency, our public squares, the cities, etc.?

How do we make room for all of them? And I do think that we can do that without saying we have to take this down to put that up or vice versa. Right? It's kind of like in any relationship, I think if you try to win at the expense of someone else, I think that's problematic. And I feel like that can be an endless cycle where, well, now, next time you win.

No, I'm not. So imagine you stick it to me, you know. So now what we do, we actually, like, get anywhere constructive and build. Whereas I think if you just keep growing the pie and doing that addition that I'm describing, then we can say, okay, there is room for all these different stories and all these different stories allow more people to engage with the American dream and history, which I think to me is important because I don't want history to feel like it's exclusive.

So to me, it's a game of inclusion.

Doug Exton: So and I think that's a wonderful way to close out the talk that you just gave. And thank you again for all of your insight and all of your your knowledge that you just shared.

Raffi Andonian: Thank you.