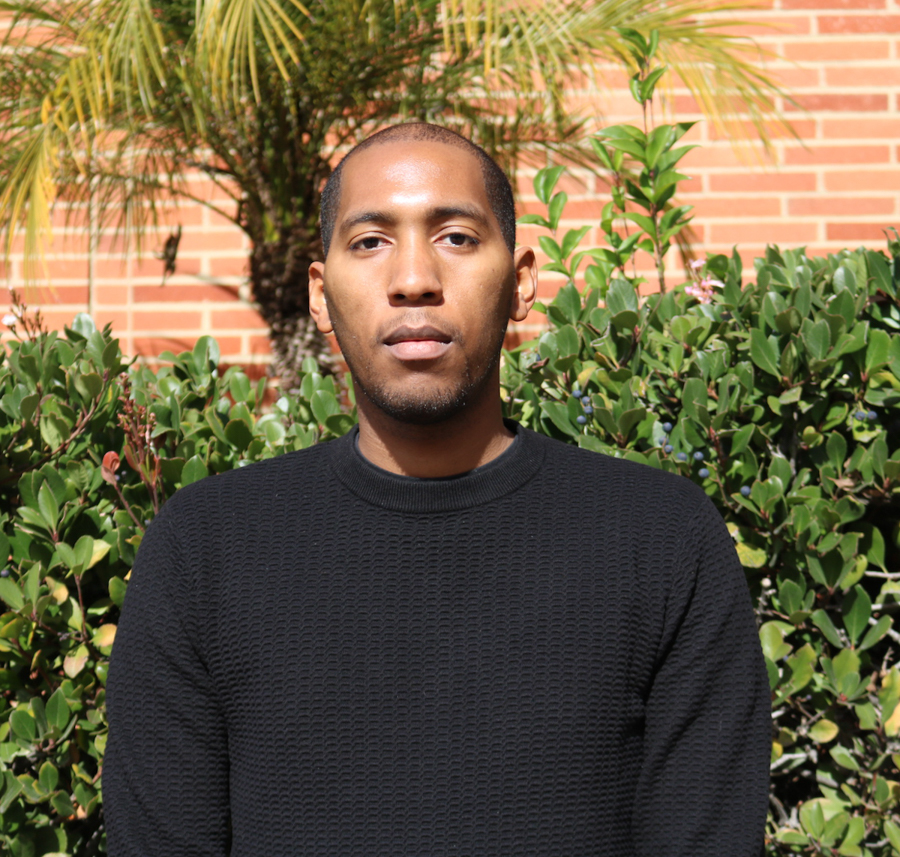

Kyle T. Mays

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

Doug Exton: This program is funded through a more Perfect Union, an initiative of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Today we have Doctor Kyle T. Mays assistant professor of African American Studies, American Indian Studies, and history at UCLA to explore an Afro Indigenous history of the United States.

Kyle T. Mays: Thank you, for the introduction, and I really appreciate it. glad to be here with you all virtually. And I am the author of An Afro Indigenous History of the United States. I am from the, the state of Michigan, and I am African-American and Saginaw Chippewa. Saginaw Chippewa's a tribe in, sort of the middle of Michigan.

And, so today I'm going to go ahead and begin. So one of the first questions we can really explore is what, in fact, is, Afro indigenous history or, for the academic audience or sorry for the term, what is the relation between Blackness and indigenous here in the US in particular? I have a particular focus on the black and red power movements, really, between the time from roughly 1966 to about 1978.

Focusing on, issues around ideology and practice and thinking about connections, especially between, African Americans and indigenous peoples. And what I like to say, the aftermath of settler colonialism and white supremacy. But also, I have a little bit of popular culture in there. So the person, to the left here is my great grandmother, Esther Shawboose Mays, or her indigenous name, .

Now, she came to the city of Detroit in 1940. And shortly thereafter, she married African-American man. And she became a well-respected elder in the city of Detroit. and they had nine Afro indigenous children who are my, aunties and uncles. And, she was deeply, committed to the education and the cultural, component of learning for, for children and especially her home was always open, for indigenous children in the city of Detroit.

In, mind you, this is a city of Detroit, especially the major U.S.. She was active in the aftermath of the 1967 rebellion, the most expensive in U.S. history, one of the most destructive. And it, changed the city forever. But as a side note, it was it that, that that was not what caused a largely excuse me, business class and white residents to leave that by leaving, at least since the 1940s, a major misnomer that the rebellion caused all these people to leave.

They had been leaving, for way before that. Businesses as well. And my great grandmother used to call it an urban indigenous remains. And what that means is an indigenous woman who's deeply dedicated.

To an indigenous, future for youth, for everyone, utilizing feminism specifically within the urban context. So in the post-World War Two era, you had many, native people moving to urban areas such as Detroit. So just Chicago, such as Los Angeles, New York and so forth. but we often think of native people as living in on reservations.

But in fact, at least since, 1990 and certainly before then, the majority of native people have actually lived in urban areas. Right. And I haven't seen the 2020 census numbers yet, but it was considered 78%. So close to 80% of native people live in some urban context. and as I mentioned, her children were raised, in the heart of black and red power activism, radicalism and so forth.

So for context, Detroit is really a hub in the US for like our, radicalism and activism. So whether that was, Grace and James Lee Boggs in the 1960s, and a Republican who after who I'll mentioned a little bit later, Malcolm X, gave some of his most infamous speeches there. so Detroit is really a hub for black nationalism, radicalism and so forth.

And this particular etching here is my Aunt May's at the podium, and she founded what was the third of her public school created with a Native American curriculum called Medicine Bear American Indian Academy. Now, the importance of this school was it was created in the 90s, right after or at least, during the, crack epidemic in Detroit, massive poverty and so forth.

But she thought indigenous peoples had a future, even in a majority black city of the city of Detroit. So she founded this school, and it was an important opportunity. So now, I mean, artists, activists and so forth were very much dedicated to understanding and remembering her particular legacy in Detroit.

So, there's a fancy term often use called settler colonialism. And let me break this up for you. Settler colonialism is simply this. It is a non indigenous population coming to a particular land, taking over their land through various means. So this is, biological warfare. It could be, various sorts of wars, the signing of treaties, coercion, all of these things lead to a settler colony.

And the important thing here is that these settlers don't come just to exploit. So we'll say classic colonialism, where people might live elsewhere, you know, say, you're in Belgium and you have the Belgium, Congo or whatever, right? And all the reasons you're can go back to the home country, settler colonialism is different. And the fact that those people are there to stay and are actively, in the population grows and they do say so think about, for Gen X or millennials, think about what you learned in high school about indigenous nations and your particular area, or what you did not learn right.

I'm assuming the majority did not learn a whole lot about native histories, outside of early U.S. history. Perhaps. Now, if that's the case, that is also a product of settler colonialism. So there's no need to feel guilty about what you did not learn. The point is, settler colonialism is meant to continue to occupy and take land from indigenous peoples, right?

This has contemporary consequences. Today, for example, when I talk about colonialism or dispossession in urban areas where, people are living in Los Angeles, where people are unhoused, where, rent prices and the inability to own homes are so sky high that people can no longer afford to live. When the police actively tried to, remove certain populations as well.

These are various forms of displacement and dislocation, and leaving people really without refuge or without without housing. and the other one, of course, is the issue of mass incarceration. I think about what is the point of a prison. Now, we might think that it's for punishment or rehabilitation. And many of the studies historically, today suggest otherwise.

That's not really how that works. And often the point is to say the people and exploit them. But to me, these are very much logics of settler colonialism. So let's jump right into the black and red power movement, which I have here with the, slash impossibilities under colonialism. So, I think we might often think that black and native people are natural allies.

And I will end discussing that in more in depth. Like it's not always the case. Even during this particular moment, there were moments which I'll get into, but many native people likely felt the way that Vine Deloria Jr, who wrote this originally in 1978, republished in 2000, said minority groups are often astounded to learn that the Indians are not planning to share the continent with their oppressed brothers once revolution is over.

Hell no. The Indians are planning on taking the continent back and kicking out all the black, Chicano and one Asian brothers that made the whole thing possible. this isn't as anti other as it might seem, but it does in fact center that the US has native land and native peoples are tired of being ignored in the pantheon of discussions around civil rights, around, Asian-American rights, around lesbian rights, at the time and so forth.

They wanted to make sure that, centering indigenous peoples in return of Land was central to their understanding of power and justice. But that wasn't really the case in a very mainstream center, with a few exceptions. This is not one of them. So this is, Republican New Africa, founded in Detroit in May of 1968. Henry Milton and his brother, changed the name right of Obadele.

And they formed this group with what they called the Malcolm X doctrine. And that is the belief in black nationalism, in, owning land. Now, they base a lot of this on what had happened to the Cherokee Nation and the rest of the, five tribes when they were removed from the southern states. Now, they one of the five southern, states for compensation for slavery.

So there's a lot of discussion today around reparations, which I'll get into a little bit later. Right now, the key question here is that it's a contradiction. Of course. How can we talk about returning? this land or why people are occupying that land without also thinking about returning the land to indigenous peoples? It's a historical question that they never, engage with directly, even though there were aware of that history.

But they wanted this for compensation for exploitation under, slavery. But it is something to really, really consider. Now, another thing that Deloria, two slides ago was essentially said in his book, Custer Died for Your Sins. an Indian Manifesto published in 1969. Was that black and native, struggles specifically for the black and white power movements had very little in common, and I think there's something to that, but it's something also to consider.

So what is red power? Essentially, you can think of the U.S nation state for not honoring the treaties they wanted. Again, the US you honor the treaties and the United States had violated every city they ever made. A native nation. The whole notion of indigenous sovereignty and this is a legal, term as well, something that native nations and peoples have other, other minoritized, oppressed and racialized groups in the United States that they have a treaty relationship with the United States government.

What the United States is supposed to honor. They were, during this time reclaiming and asserting indigenous cultures. And if we're talking about, reclaiming land values, in some ways it's anticapitalist. And in some ways, black power, there's some shared values here. So black self-determination, a critique of U.S. democracy. also, just like native peoples asserting a black nationalist, culture.

So whether that's, Black Harvest, whether that's the, iconic Afro of Angela Davis and others. And for many of the groups, these things are, anti-capitalist as well. two groups in particular. To focus on here are the Black Panther Party, founded in 1966, and the American Indian Movement in 1968. Now the Panthers are founded as a response to police brutality in Oakland, California, and in Twin Cities in Saint Paul, Minnesota and Minneapolis, Minnesota.

They founded in 1968 for exactly the same reason, but they hadn't seen it. The Panthers said, the attention they had garnered in the media and thought, this is a great way, but it's a more slightly and for black, the Black Panther Party and some more international realms and more, issues of solidarity. And for the American Indian Movement, focusing specifically on treaties and stopping the, violation and the eradication of native peoples.

And many of those histories are to our very, we'll say, male dominated. But we have to consider the role that many black and indigenous women played. So sorry, the Sardar Shakur, who is still, in Cuba at the moment, in a particular essay she wrote to my people, said, they call us these or we did not rob and murder.

Millions of Indians are ripping off their homeland, and cultural pioneers. Right. This is another example of rhetoric of, settler colonialism that, Assata Shakur, the godmother of the late rapper Tupac Shakur, who what she is actually challenging, and we might often think about these things without little consequence, but they certainly have an impact. the other thing is women of all nations.

So women of all nations was founded, in South Dakota in 1978. their first meeting had over 200 women. There. And they focus at least on a few things environmental racism and reproductive rights for native women. reports, anywhere between 42 to perhaps as high as, over 60% of native women in this, era in the 1970s had experience, or sterilization.

And they were really, one of the first groups to bring this to attention, at least as it relates to native women.

And so they say, Indian women have always been in the front lines. And the difference in the defense of our nations, only by throwing off the yoke of colonization with the strength of our spirituality, it will we survive as peoples nations. Right? And they also tried to, get a wide variety of forms of solidarity with lots of different groups.

Now someone, who is very active in, in good relation with native peoples was Stokely Carmichael. So in a talk he gave called the Red in the black, in Twin Cities in Minnesota, they were fundraising for the defense of Dennis Banks and others that all of us must struggle against capitalism. The red man is struggling against capitalism.

He has been a vicious victim of capitalism. It is on his land that the most powerful imperial system isn't built at its very expense. Right. So Stokely is putting this out there, and there are many African-Americans deeply engaged in access our duty. So Angela Davis, who is still in the struggle, was one of them. So she went to Wounded Knee in 1973.

And I always tell young activists, this part, often it's about showing up for people, right. And you need a lot of coalitions with people to create change. And while she was not able to actually, go and to pass the baton to her and to sign up as important and demonstrate, at least symbolically, forms of hope in solidarity between black and native peoples.

And here she is in Detroit in 1974 at the National Alliance and Repression. And so her left, speaking at Cobo Hall. To her left is Clyde Belcourt, a co-founder of the American Indian Movement. Now, these acts of solidarity are symbolic in some ways were very important, right? They're very important. back to, Stokely again, who changed his name to Kwami Terry.

He was perhaps one of the only, people that acknowledge that this, that the US was indigenous land. Right. And he and the Black Panther Party, the Black Panther Party, would document all of the actions of the American Indian Movement. within their particular newspaper. So Turei says anybody who think seriously about working on behalf of the Redmond must syllabus or the land on which we live, on which we inhabit, which really supported that land, belongs to the Red man.

He must come first in any dealings with the land. Now, this is a powerful statement that I haven't found very I haven't found any other, African-American radical group in the time making such a proclamation. In here, at least from the late 1970s to the 1980s, you have here the first, annual International Indian Treaty Council on the Water Conservation.

And, this is right after the 1977 Geneva conference, the United Nations, where you had a lot of native activists here proclaiming that, their treaty should be honored. They need more protections for water rights, and a return of land. Right. And acknowledging that indigenous peoples, exists within the international structure. And you also have an African-American man here, Bob Brown, who's very much invested, in Native Struggle and continues to do so today.

And he was a representative of the all African revolutionary peoples Party founded, Kwami and Kuma and really advocated for by, Kwami Terry and Kwame Nkrumah being the, president of Ghana at the time. No shift in popular culture. Popular culture is a significant part of, transformation and how people actually understand it, especially for young people.

And by popular culture, I mean it's probably some music. film art, television. And so for social media, we might consider a form of popular culture, Tik Tok and all these, ways in which we will produce culture. So in particular, for here on a focus on indigenous popular culture. So it's a symbol, signs and meanings for these indigenous peoples to tell stories about their lives.

Right. So about the past, about relationships, it can be about, the experience of the rest of the city. These are all the various forms of, indigenous popular culture, or do so within the context of a settler colonial capitalist society. And I think that's important to acknowledge. And it demonstrates indigenous peoples, modernity or their desire to be seen as people of the future.

So one of the things about that indigenous, creatives have to respond to is always being considered people of the past and always being asked to produce things. set the palette, colonial desires about what art is supposed to be, what indigenous art is supposed to be. And it can be a challenge for many of them. So again, what are the the these modes of popular culture esthetics, visual art, writing, social media means music, dance, film and various some of the media and those things that I mentioned before.

But again, it's about future isms so coined by artist scholar Grace doing, she says. Indigenous Futurism is a growing movement, but not limited to Indian country, where native peoples dare to reimagine societal tropes, alternative histories, and futures through the exploration of science fiction and subgenres. You can see this year of comics, fine arts, literature, games, and various other forms of media.

And I ask this, particular question here to consider for everyone, but just imagine and think about how many just well known famous indigenous people do you know? And I'll pause here just to think about it.

Right. And and just kind of Latin, if I ask you name me ten just famous African American artists. I'm sure you could do that pretty easily. But this also, again, is a function of settler colonialism. That it's is something you just, you know, you don't really know. And the importance of indigenous, popular culture here is you produce three dimensional, views of native peoples, that we're not people simply of the past, but we exist in the present and will continue to exist in the future.

So the importance of indigenous representation, you know, half of Americans say that what they were taught in school was inaccurate. So this is a study from illuminators, and 72% believes significant changes to the school school curriculums are needed, right now. We can go to the example most recently, of the Washington Football Team, who are now the Washington Commanders.

Right. And so what portion of the change your name? Obviously, native people have been resisting, protesting for them to change a racist, name and emblem on the NFL team. Same thing with the. No. Cleveland Guardians, formerly the Cleveland Indians. Energy wasn't they finally change it and it was a combination of native activism bringing awareness for this for decades.

And of course, the murder of George Floyd. And companies are pledging, millions of dollars to protest, systemic racism. And yet you still have racist mascots, which is a huge contradiction. I'll never forget watching, it leaves the Kansas City football team and they had ended racism in the endzone. And people can't do that. And yet they still have the the name the Kansas City Chiefs.

And if you look into the crowd, all sorts of racial stereotypes about native peoples. So it's just a huge contradiction. and representation, has its place in social transformation.

Now I want to, spend a little bit of time because I get this question all the time around cultural appropriation versus appreciation. And I'll start with appreciation. So you're certainly engaging with the culture and the people, right? That is, you know, so you're a hip hop head. You hang out not only with the music, but you, you know, you hang out with white people and you care about white people.

You understand the context and history of that particular culture in the most respectful manner. You see that group as being dynamic. That is, you don't see them only through the lens of, say, for example, hip hop culture, because you continue learning from them too, right? That's important. cultural appropriation is much more, much more utilized today, I think.

And I think there are some very good takes and some very careful takes when it comes to cultural appropriation, but it's simply the, dominant group taking the culture of the people and using it out of context, and most importantly, profiting off of it. you know, understanding, history and the context in which the cultures produce.

And they just sort of see people as very static. This is what they're known for, and this is what they do. This is how they do it. For example, you might see people appropriating, queer language, like weird language in particular. You might see people appropriating, hip hop culture. And then they are doing this and then profiting off of it.

Or very recently, you had a lot of, white creatives taking the dances that white dancers and creatives had made on TikTok and then profiting off of it. These are examples of cultural appropriation, because it's really about power and your ability to profit off of such things. this is another one. So again, I mentioned at the beginning that we can often assume that black and native peoples should be in solidarity and and don't commit to those things.

But this is from 2017. This is a pulse of Nicki Minaj. Right? And this has,

It was it was for paper magazine. And this has all the things around, anti black women pointing Indian and, holes of things around race, gender, appropriation and so forth. So this is, she had a character of Pocahontas, but, it's mostly Pocahontas. And she took the Hogan as part down. And it was offensive to many native people, especially native women.

When native women experience, sexual assault, two and a half times, two out of five times more likely than other groups. And it is it's just inappropriate in a lot of ways. But what was missing, though, is no one really knows who the artist was. And it was Argentinian artists, right? So while she put the caption on and perhaps approved the image, it was a particular artist who made it.

This artist makes racy, risque. Disney art like this in a variety of contexts, but, there's a lot of anti black woman in the rhetoric in response to Nicki Minaj as well. And she's a celebrity. And I'm not too much into defending celebrities, for the most part. But but the, the dynamics. It's like when you know someone from a oppressed group, commits an act like this, people seem to be more offended and have much more vitriol.

And part of it, because you don't expect that to happen. But we should expect anyone to that then we should expect. But we shouldn't be surprised if anyone engages in various forms. appropriation, prejudice and so forth, because, as Abraham Kelly is noted. That many of us can adopt, racist ideas. And I would add that maybe he was kind of, a settler.

Colonial ideas, low.

and this is, another example here. So, this is Reservation Dogs, the show on Hulu, which is now in its second season. And in the first season, there's a lot of commentary, you know, getting it from friends, colleagues. And so for about the lack of Afro indigenous representation, given that it's in, Oklahoma and there's not a lot of references and the music used.

And so forth. in particular, this particular video, I'll encourage you to go check it out in your own greasy frybread. It's it's pretty funny, but people are like, oh, this person, the appropriating black, like, southern culture, what they grew, and so forth. And I would encourage you to go check it out. just so see and to me, that wasn't even really appropriation in one sense, but there was a particular scene at the end of, episode one where this person, and I yeah, I would just I would encourage you to check out episode one, in particular, just because it's not really the music that's appropriation or might be

deemed anti-black, it's how the writers wrote something, that I thought was a scary, but it's difficult to explain about the actual video. But do go check out, episode one and the rest of the series, which is fantastic. By the way.

So, I want to spend some time here, wrapping up and thinking about what are some of these aftermath. And I think kinship, is important. So when I say kinship. So I am Saginaw Chippewa and we have a clan system, and I am a part of the, Mercado them or Bear Clan. And every clan has a particular responsibility within the nation.

There's even a clan for outsiders. Right. And what a what kinship does is clearly define the role of people within that particular, society. Now we're moving towards the aftermath of settler colonialism and white supremacy, and we have to think very clearly about what our different roles are to each other, to the land, and to our futures. So I think an important discussion right now is the reparations debate.

So I'm in California. the state legislator has been toying with various, issues on our reparations. So what was known as Manhattan speech, was formerly known as versus beach is one example, and it was just awarded back to the Bruce family of Saginaw from a black family in 1926, 1525 or 1926. And it was just given back to them.

they had lost all sorts of wealth and land. And now what's important about this. Is and I'm not opposed to reparations per se, but many of the articles, in Los Angeles Times and local news have mentioned very briefly, but not discussing full the where did the Bruces get this land now, they weren't the ones who actually took it away from indigenous people.

They sort of just occupied it later on. But in release, in discussion of reparations, this should be a simultaneous discussion. if you're going to compensate these people and return that piece of land, what about returning land to indigenous peoples? Right. And so, William Darity and Kirsten Mullin in their book From Here The Inequality on Reparations, based on their calculations, say.

They would require, expenditure as large as 15 to $20 trillion. it's laughable, right? What's laughable is not the actual number per se. Like he actually calculated a host of, things rather than slavery, Jim Crow. And so for it probably makes sense. Let's now what's the funny part is the United States does not pay African-Americans 15 to 20.

Surely knows, for reparations. I just don't see any way that it's possible. And the second part of this, is where do indigenous people fit into contemporary discussions of reparations? So if the foundation of the United States are rooted in anti-Blackness, rooted in slavery and the dispossession of indigenous peoples, and whether that's, the Declaration of Independence or this Constitution, whether that's Alexis de Tocqueville of democracy in America, The Federalist Papers, if you read all of those, you'll see various forms of anti-Blackness and anti-indigenous into it within those documents that are so, sacrilegious to and paramount to our understanding of, you know, some accuracy.

And land was central to them. So how can we have discussion reparations without also discussion of returning them land? And so the Indian collective, a collective of indigenous peoples committed to the land back movement, argue that it's a political framework that a lot of us deep in our relationship with across the field of organizing movements, working towards true collective liberation.

And I think the most important part here is either allows us to envision a world where black, indigenous and policy liberation coexist. and the number of years in 1776, 1.5 billion acres have been acquired. Sea stolen cores whatever from native peoples. And finally, they argue that white supremacy should be dismantled. You have to put indigenous land back in the hands of indigenous peoples.

So my, I'm wrapping up here, my colleague, and good friend and starts goes by the social media de melanin. Muskogee argues that fundamentally believe our arrival and black liberation and admission of sovereignty will certainly require us to remember who we are outside our institutions, ideologies and imaginations. And I think I think that's a that is deeply profound.

And it takes a lot of work to do that. And I think. Activism, I think popular culture and representation, I think all of those things, combined are important to really try to see ourselves as very different, not only see ourselves different, but relate to each other differently as well.

and so what can this look like? And I want to begin with the quote from queer black feminist Audre Lorde in her essay learning from the 60s. She says any future vision which can come as almost by definition, must be complex, expanding, and easy to achieve. I think many times we can assume that, these things can just be very easy, that justice can be easy.

And I assure you it is not easy at all. and if we're really to have a robust conversation about how oppressed peoples across the board, can get liberation and freedom, or when someone asks Nina Simone, what does, freedom mean to her? This is a great song, for she said, no fear. I imagine if, every oppressed person could generally live with no fear, whether that's black, indigenous, queer, all those things so forth.

Great. You you don't. You can be vulnerable without having to fear consequences. Right. imagine that women's reproductive rights and so forth. But all of those things require a deep understanding and kinship and relationships with one another. And one thing I would love to, to see in a variety of communities is multi-generational, sitting down, with one another over a meal and just hanging out and learning about each other's histories and discussing and strategizing about our futures.

Right. I think, I have this idea about indigenous nations abducting people that would have sent, as one example, whatever their protocols are for doing that. and I think there are many creative ways, we should all get together and think about how to accomplish some of those. and I'll end right there. So, Jimmy, Gretchen, thank you very much for listening.

and I'm looking forward to, questions and conversations. Thank you.

Doug Exton: Yes. Thank you so much for sharing all of that knowledge. and also some of those examples of popular culture, because I do think, though, you know, being able to point to something, especially a more recent event, you know, like that Nicki Minaj, example is one of those things where it truly makes it a lot more visible and a lot more, understandable and easier to engage with rather than just, you know, saying, you know, oh, in the history books, you know, this is how it was.

One question I did have for you is, how do you reckon with the notion of erasure, especially with history, because history is such a multifaceted and multi lens, you know, body of knowledge, so to speak. I know in your book you did mention how there is that notion of when you talk about indigenous, American history, African-American history gets erased or vice versa.

Like there is that notion that you can't have both at the same time.

Kyle T. Mays: Yeah. Erasure is is is tough. especially in a country that is dedicated to, keeping people uneducated and people sort of accepting that. Right. So, for example, one assignment I give to my students, often is I say, go home. You know, whatever you consider home, whatever place, and think about who are the local indigenous peoples, of where you live.

I always get some strange looks from people, if they know very little about indigenous history. And it's not touching them at all. It's just say and many, you know, usually 30, 20 to 30% will say, I didn't really find anything. And my response to them is, this is how settler colonialism works. It's meant to make sure you know very little, or to grow up not knowing very much about the local indigenous population right now.

And I was like, take that as a lesson to go back and think through how that happened, systematically. And, also that's how you reach your audience because it's one thing to learn from a textbook. and I know teachers are smart, so I'm not putting this particular burden on them, but it's another thing to, you know, take people, if you have local elders from and from that particular community, take them to the land and learn about that particular history.

It does wonders, for people.

Doug Exton: Kind of continuing off of that, you know, in the notion that, you know, the loss of knowledge, you know, and that notion of, oh, I didn't find much in your opinion as we are in moving towards the future, you know, increasing technology, increased access to knowledge, but at the same time, we're moving further away from, you know, the settling of Jamestown and all of these things that happened on the eastern coast of the US, where there tends to be a lot less visibility in some areas, with indigenous tribes, you know, due to various mechanisms.

Do you think moving forward that some of that might be lost or that it might be more accessible and actually more easy to engage with it?

Kyle T. Mays: I mean, it's difficult. So, some positive examples that I know of, my colleague Elizabeth Rowe at American University has helped, various folks. And, another colleague, I actually met her, in Baltimore, a Lumbee woman, they so Elizabeth has created a, an app to help, like, people. And they're walking around in Washington, D.C..

It sort of the doctor. Ashley Minner to create an app as well, for, for East Baltimore in particular, so people can kind of learn about those local indigenous histories. And I think technology is a powerful tool in that sense, on the other hand. And that's very interactive. Pretty cool. On the other hand, though, I often see more and more students and, wanting to read.

And it sounds strange, but, there are a lot of things that distract us, you know, whether you're on Instagram, Twitter or just hanging out and taking the time to sit down to read, you know, for an hour or two hours seems to be a, quickly depleting, art form. Right? Unless you're just an avid reader, because you like to read, but and it's hard to really get them to read.

So. And they're always exceptions, of course, but just in general, anecdotally like this similar reading. And I'm like, when I was in school that what what do you mean? I see less reading. But you know, there wasn't there wasn't all of the, Chao at least as an undergrad, it wasn't all the challenges of Instagram. Twitter. Those are just starting out.

So it's a challenge.

Doug Exton: And in your work, have you experienced any illnesses where, you know, labels can either be a positive, aspect of movement like the black power, the Red power movement, or have they been used in a way that essentially not rewinding the clock, but a, you know, some of the momentum of these movements or creates, you know, internal clashes within these groups?

You know, especially thinking of telling, you know, an Afro indigenous history or even just an African history of the U.S or an indigenous history of the US.

Kyle T. Mays: Yeah. I mean, there are certainly instances of, also that people don't want to see these things as, as a form of solidarity. some native people don't want to be lumped in with African Americans, but historically and today, because they're like, we're not a minority, we're we're nations or we're treaties and we're sovereign. but what do you tell that to Afro indigenous people like myself or my cousins?

Right. It's a bit more complicated than that. And. Yeah, and the other part of that is, some African Americans can easily just, just erase native nations. So, paraphrasing the Combahee River collective statement from 1977, when they say when all black women are free, everyone will be free, or when all essentially when all black people are free, everyone else will be free.

And are you? So just accept the the way that it is and like 95% of that is true. But another question to add to that is where the native people sit in that formulation. Because if all black women, all queer black folks. And so for all trains, black folks are free tomorrow, what does that say about returning land to indigenous nations?

And, certainly there are many or at least a handful of folks who who would think differently about that. But that still doesn't account for indigenous women, indigenous and folks, indigenous queer folks, which for them, it's so fundamentally about returning land. Right? Land is is sort of the key thing here. So we have to think, that's why I see these things as very connecting.

And they should be looked at simultaneously.

Doug Exton: And the last question I have for you today is, you know, this program is funded under the a more perfect union initiative from the National Endowment for the Humanities, with the focus of, you know, exploring the history of America as we approach the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence being signed. You know, in what ways can we as a country help move the needle towards a more perfect union instead of letting it go backwards?

So how do you see the exploring or the visiting? Or as this book is part of the Revisioning History series, re-envisioning history, moving the needle towards creating a more perfect union of this, you know, one country and one society, even though obviously there are multiple groups and multiple different identities under that umbrella.

Kyle T. Mays: Yeah, I it's it's difficult, because I think like a native people and people who are committed to justice have been trying to do this for, for centuries. Now, I know the U.S is still a young, young nation, but I've been trying to do this for a couple of centuries at least, and whenever those groups most committed to justice actually try to radically transform society and in many ways simply make it better, they get imprisoned, exiled, they get murdered, and so forth, and so what I would hope is that, people would sit down across races, gender, sexualities, drop their ego.

And I think many times, although certain, created equal many of those kind of egos about, you know, what are your way. And so something that was messed up. Some people you don't know what you don't know. And I think there's often an assumption that you should just know. And I'm like, no, we all grow up differently and you have to unlearn a lot of things.

And it's difficult to do that and make a mistake. Oh, wow. And so I or in live in life or and so I just wish, and not even just more grace. Right. I don't mean necessarily in the Christian way, but if someone wants to take it, that's that's called me. But just more grace and love for people to make mistakes and also be held accountable.

Because if there is no love with that, it's just going to create more tension and long term issues. Right? And I'm not saying everyone has to get along or anything, but you do have to do everything with love.