Dr. Caroline Heldman; Dr. David Gray Adler

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

Doug Exton: Thank you so much for joining us for tonight's conversation on voter apathy and disenfranchisement. This is a program conducted by the Idaho Humanities Council and funded by the. Why it matters Civic and Electoral participation initiative administered by the. Found by the Federation of State Humanities Councils and funded by the Andrew W Mellon Foundation. If you're not familiar with our organization, I encourage you to check out our website, idahohumanities.org.

I'd like to remind you all you may submit any questions using the Q&A feature located at the bottom of the screen. With me tonight, our two wonderful guest, Doctor David Adler and Doctor Caroline Heldman.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Great. Nice to be with both of you tonight. Good evening. Caroline.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Hello, Doctor Adler. Thank you, Doug, for hosting us.

Dr. David Gray Adler: I just Doug, this. I can't, I have to say, this is such a timely, subject for our conversation tonight. Here in Idaho and across the nation. People are greatly concerned about, particularly about disenfranchisement. I know Caroline follows this closely on a daily basis, and we see, Congress up in arms about it. We see state legislatures trying to suppress the vote.

Democrats fighting back. This is this is a time when the forces are gathering on on both sides. Don't you think, Caroline, for this is this is the battle for the continuation of democracy?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Indeed, David. I mean, I think we've seen, a bigger push and rollback in the modern political era than we have seen really, since the push for Jim Crow. And I'm going to start us off with a PowerPoint presentation. Just looking at a brief history of voter suppression in the United States just to to get everyone on the same page.

And this is I'm going to say it's five slides, so not very, detailed, but it gives you a really good sense of where we started and where we've come in terms of voter rights and then voter suppression efforts that are happening right now. So at the founding, we like to think of, you know, our country as being this grand experiment where we are extending the franchise and we're including all of these people in this new form of governance.

But in reality, not only were women not able to vote and, Native American people and Black people not able to vote and other people of color, but even most white men, were not able to vote. Right? So only about 10% of the nation's population at the time of the founding was able to vote. And if you recall, you know, there at the start of, of the founding of our, our nation, when we started having those conversations, we had about 4 million people.

And then within a matter of decades, we had about 13 million people, but still only about 1 in 10, was able to vote. So I'll start by, by really level setting here that we baked voter suppression into our founding documents. So we have these ideas about what constitutes democracy, right. And of course, people will quibble and say oh no, we live in a republic.

Well, that's a form of a democracy, right? It's one where you elect, representatives, to represent you rather than, you know, a direct. We tend to think of democracy as being direct, but republic democracy, whatever term you want to use, there're three really primary guiding principles. The first is political equality. And we tend to think of this as the cliche of one person, one vote.

So, the who gets to vote is fundamental to how we think about democracy and of course, political liberty. You know, the idea of freedom from government interference and the rights that go with being a full citizen. And then a popular sovereignty, which is the idea that government only has legitimacy if the people decide the government is legitimate.

So if you only have a sliver of the population who is able to vote, that means that popular sovereignty is by definition limited, that political equality is by definition limited. So we started off with these grandiose ideas about what our democracy would be, but we actually baked in limitations on who counted as a full citizen very, very early on.

So if you look at the history of our country in terms of democracy, I like to think of it as, a constant push for the expansion of democracy in the sense that more and more people are allowed into the franchise. More and more people are allowed to cast their vote, which over time strengthens our democracy considerably.

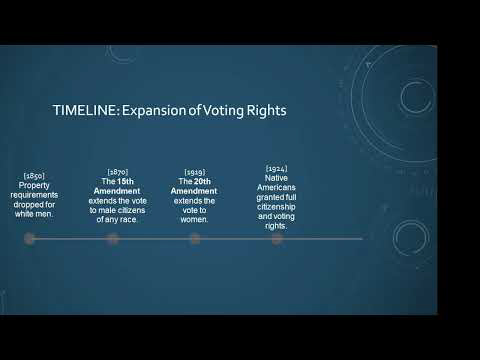

So when you look at the big kind of burst expansions of voting rights, first, you have the property requirements drop for white men. This happened at the state level initially. And then happened, it happened nationally, in the last kind of barrier to fall was in 1850. So the first, extension of voting rights is for white men.

So, it goes from being, you know, 10% of the population to over 50% of the population being able to vote. And then in 1870, you have the 15th amendment that extends, the vote to male citizens of any race. And I'll put an asterisk on that, because we wouldn't need a voting rights amendment, Voting Rights Act of 1965, if the 15th amendment, you know, after the Civil War, if that amendment had actually been put into place.

But what we actually see is an informal system where Black men and, Black women don't have the vote yet, but Black men, have their voting rights curtailed through a series of Jim Crow laws that extend to voting. And we'll look at that in a moment. Then the next big push is the 20th amendment that extends the vote to women.

But again, for Black women, we would need the Voting Rights Act of 1965 because, voting restrictions in the form of grandfather clauses, in the form of poll taxes, so having to pay money, not being able to vote unless your grandfather was able to vote, and then literacy tests. So, for example, tests asking Black voters, how many, how many bubbles are on a bar of soap.

So impossible questions to ask. Again. So even though we see this formal extension with the 15th amendment allowing male citizens of any race to vote, and then the extension of voting rights to women with the 20th amendment, with goodness, that's a reversal. Sorry, the 19th amendment in 1920. We actually do not see voting rights formally put into place, for Black Americans until 1965.

And it's worth noting that Native Americans were granted citizenship and voting rights, in 1924, they're allowed to vote in federal elections. We've also at this time, as I mentioned, we have this rollback, this restriction of voting rights happening at the same time. So as our country is becoming more democratic, there's also a backlash against certain, groups actually fully participating in democracy.

So, in 1889, we see, the first Florida becomes the first state to pass, a poll tax that specifically affects black Americans. And very quickly, we seen nine other southern states pass, poll tax laws. And then Mississippi passes the first literacy tests in 1890. And so, again, the voter the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which followed on the heels of the civil rights Act of 1964, was put into place in order to reverse all of the restrictions, on voting that have been placed informally and sometimes formally, on Black Americans.

Once they got the right to vote after the Civil War. It is worth noting that the Voting Rights Act has been gutted with the Shelby decision. In 2013, the Shelby provisions. So essentially, we had a system where, the Voting Rights Act allowed the federal government to scrutinize states, any states that had a history of disenfranchising Black voters.

It allowed the federal government to look at those states, any laws they wanted to pass in terms of voter rights if they had a history of, disenfranchising Blacks. So, what the Shelby decision did is it just gutted the Voting Rights Act. It took away the requirement that any time states with this history tried to pass new voter restrictions, the federal government could look at it.

It just took away that federal oversight. And so what we saw with when the Supreme Court, made the Shelby decision, which I'm sure Doctor Adler will be talking about in great detail, what we saw immediately was, over 30 states, put in voter restrictions. I mean, within weeks of the Shelby with, within weeks of the Shelby decision and the Voting Rights Act being gutted. Then what we saw is, voter ID laws passing,

36 states from 2013 to 2017, and we can have a long conversation about what voter ID laws do. On their face, they seem very innocuous, right? You use your ID when you go to get alcohol, you use your ID, when you apply for things. But the issue is that for voting, ID, there are a lot of folks who are less likely to have identification.

So, for example, transgender Americans are less likely to have identification that matches their identity. Older adults, perhaps adults who don't drive any more or less likely to have ID, Black Americans are less likely. Latinx Americans are less likely to have IDs. So what these voter ID laws did is essentially, even though they seem innocuous and they seem pretty basic for folks, you know, middle class folks who can pay, you know, 80 bucks to get a new ID they actually ended up being highly discriminatory in, in terms of who they turned away from the polls.

But the bigger issue was voter ID laws, which a lot of us have been talking about for over a decade now, is the fact that they are addressing a non problem. So voter ID laws, when they were initially the first wave that passed in 23, 2013, right after the Voting Rights Act was gutted with the Shelby decision. What happened immediately, is that states started implementing these new laws and they cost, that one year alone, $20 million to implement.

So you would think at the state level, if you're spending $20 million to change your laws, it's got to be addressing a problem. But the issue is that, voter fraud is actually not a problem in the United States. In fact, you are 37 times more likely to get struck by lightning than you are to engage in an act of voter fraud.

And this is not my data. This is actually data coming from the Bush administration. So when George W Bush was, in power, he directed, the Department of Justice to look at voter fraud. And they did a five year study, and they found that voter fraud was negligible. It's simply non-existent. While there were a handful of cases, most of them were a mother who thought that she could go and vote for her daughter, who was away at college using her daughter's ID these sorts of instances where people were simply unaware of what they were doing.

Voter fraud is not an effective way to throw elections, right? It would just require an extraordinary amount of, coordination, which would very easily be picked up by election officials. So there's a reason why, you know, voter fraud is not an issue. And we used to know this and we used to know that it was very expensive to address a problem that wasn't a problem.

But today, we now have 36 states that have passed voter ID laws, which are relatively still expensive to implement to address a non problem. So you have to look at this and say, well, what's happening it. Why pass laws to address a non problem. What's what's really going on here. And what we know is that the states that have passes is a very partisan measure.

Right. So whether you're a Democrat or Republican, I think we can all get behind the idea that, folks should we should be enabling voting. Folks should be able to vote. It's part of being a citizen in the United States. It's part of, you know, strengthening our democracy. I don't think anyone has can really push against that.

And so any restraints on voting, I think should receive really strict scrutiny, especially things like voter ID laws, which end up being highly discriminatory in how they're implemented, what's happening right now in 2020 is, we all just lived through the last year of the big lie that the election was fraudulent. Again, we know that it was not, not only do we have 60 plus court cases, many of which were overseen by Trump appointees, that dismissed the idea that there was fraud in the election.

We also have a number of Republican states and state Republican state election officials who are pushing back against the narrative of the big lie that the election was fraudulent, that however, has not stopped, the 44 states where Republicans have proposed over 250 very stringent voting restrictions. So, to rephrase what I said, at the start of this, we are in an era where, we are passing more restrictions on voting rights than, than any time in the modern era.

And it looks very similar to what was happening after the Civil War amendments passed. So shifting really, quickly here to what the real problem is in the United States, a problem that was not a problem in 2020, low voter turnout. So we don't have an issue with voter fraud in the United States. We actually have an issue with voter turnout.

And it started in the 1960s. And we can unpack some of the reasons here. But the biggest reason, as identified by Robert Putnam, is the advent of television. So television did something really interesting. So the way so voting is, very much predicted by how connected you feel to your community. And the idea is that the more you connect with your community, the more likely you are to turn out to vote in an election because you feel more a part of your community.

And this is again, Robert Putnam found this in his classic book, Bowling Alone. And so he's scratching his head and saying, well, why? Why is voting declining? There are people feeling less connected. And he found that indeed they were. That what television did? Was it privatized our free time. So we were no longer hanging over, the fence and talking to our neighbor.

We were no longer going to the PTA meetings at the same rate we were. Instead of joining bowling leagues, we were bowling alone. The title of his classic book. And so political scientists and others who care about democracy have long been kind of pulling out their hair to say, how can we get people to turn out and to vote in elections?

Well, if you look at the, 2020 election, you can see that something very important happened during this global pandemic. It's a very, very small sliver of a silver lining on a dark cloud in that we relaxed voter, rules and processes, meaning we made it easier to vote. And guess what happened? More people voted. So you can see this long decline starting in the 1960s that has a couple of peaks with some high profile, contentious elections.

But look at that number in 2020. That's what happens when we actually enable American citizens to participate in their democracy. And I'll end with a quote from Stacey Abrams. It brings it back to the original design of our democracy. Right. So if you look at how far back we've, how far we have come since our founding, when we very clearly excluded various groups from full participation in our democracy, we baked that into the American experience.

And it is really disheartening to see in 2020, that we are trying to roll back the experience of democracy by limiting the vote. And I will pass the baton now to Doctor Adler.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Well, thank you, Caroline. Those, those data points in that historical timeline analyzes were superb and really helped to facilitate this conversation. Just picking up on a couple of the excellent points that you made. A couple of themes leap out at me. The first, of course, as you said, is that at the beginning very few people could vote.

And it reminds me of a classical, political theme, which is to say those in power don't want others participating. Because of course, it would undermine their own ability to set the agenda. So by disenfranchising various groups at the beginning, it made it easier for a small group of people, in this case white men, to control politics in America, to promote their own interests.

The only the only way then, for people to gain some footing, to be able to participate effectively in American politics, or any country for that matter, is to fight for their rights. And that becomes an emerging theme across the course of American history, where all those groups that finally did win the right to vote, did it as a result of strenuous efforts, whether we're talking about the 19th amendment, for example, or the right of 18 year olds to vote, which came as a result of of a nation, feeling the, conscience pangs of sending young men to war 8000 miles from home, but not allowing them to vote, in the system, or

certainly with the with the hard-earned right, for Black Americans to win the right reflected in the 15th amendment. So that reminds us that benefits, including the great right to vote are seldom handed to people. People have to fight in politics. Which then raises an interesting question for me, and that is that, because voting is the most fundamental right in a democracy, it bears a reiteration.

It is the most fundamental right in a democracy. If we as a nation aspire to be democratic, why do we see people, particularly people in power, working hard to make voting more difficult or in fact, to deny people the right to vote? And it seems to me that there's a very clear answer. It's the old political theme. The more people that participate, the more difficult it is to win power and to promote one's agenda.

Which is another way of saying here in America that those who are currently involved in the efforts as you pointed out, in the passage of some 250 bills and 44 states, to make voting more difficult, are fundamentally opposed to the expansion of democracy. That might sound shocking to a lot of people, but that's the reality. You can't assess it any other way, particularly because, fraud is a non problem, as you so nicely pointed out.

So they contrive the existence of a problem so as to justify voter suppression, which, as you noted, applies, with great force to particular voting groups, minorities, the elderly, the poor, and, and not necessarily to those whom they believe will support their own candidates and causes. Those are just some of the themes that, that emerge immediately, that suggest that democracy is in great peril.

If in fact, our most fundamental right is under attack, as opposed to making it easy to vote, which is what we assume people who are pro democracy would want to do. And isn't it interesting, Caroline, that often those very same people that want to make voting very difficult are the first to say, don't throw down any hurdles in our path to exercising, for example, our Second Amendment right.

We don't want background checks, we don't want a delay in buy, buying guns. They'll say we don't want our gun rights to be restricted in any way or, as it happens here in Idaho, a lot of the people who oppose wearing masks, for example, are among those who advocate restricting the vote and the same ones who were angry when, they were denied, what they perceive to be an absolute right to gather in houses of worship again uttering the refrain, don't try to restrict the exercise of our right.

So it's, it's an interesting paradox in our system that those very people who would make voting difficult, and thus undermining the very foundation of democracy, don't want their own causes restricted in any particular way.

Yeah. And so the concern I have. And let me ask you, for your thoughts about this, Caroline, the concern I have is what will be the success of the efforts at the state level to accomplish voter suppression? And does that make it all the more imperative for Congress, for example, to enact, what was passed by the House in early March, H.R.1, for the people before the people act, now, before the Senate and exercise, what is a clear congressional power to regulate elections in the face of the, in the face of the, opposition?

That would say Congress shouldn't encroach on state authority to regulate elections.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Well, David, I would love to hear your analysis of of whether you think these, efforts will be successful, but so H.R.1., for folks who are not familiar, is, a voting rights act that essentially restores all of the erosion that has happened since the Voting Rights Act was gutted in 2012, 2013. All of those efforts that started at that point in time.

And that means, that same day registration, is would would be the law of the land. It means that, mail in ballots would be easily accessible. It also allows, the gathering especially, which is especially important, in places like Arizona and rural areas where you're more likely to have Native American and Latinx folks, who, you know, don't want to travel long distances or might not be able to do that.

And so, you know, one person in the community could gather all of those ballots and take them then, so it's an extension. It basically takes how we made things easier in 2020 and makes that the law of the land. I think that the Senate so it's unlikely to pass the Senate unless the filibuster is, eradicated.

Right. So, I think that's probably likely, which means that we will enter a whole new era of divisive politics, the likes of which, I mean, we've seen a bit of it with Mitch McConnell, where he would bend the rules, the Senate rules quite a bit. And I think Mitch McConnell bending the Senate rules is actually why we will not see this ultimately be successful.

And that's because the Supreme Court has a packed supermajority. And I say packed, because Mitch McConnell bent the rule during the last, year of the Obama presidency and said, no, he would not, host a hearing for, Merrick Garland, who's now our attorney general. So essentially, that seat that was supposed to go Democratic.

And there's a reason why, you know, the court, why presidents appoint. Right. And then the Senate confirms, because we elect folks of different parties, and they're supposed to be able to put their person in. And the Senate having to confirm that means that person is going to be somewhat in the middle, right? You're not going to get these extremists on the court.

It's very rare that you would get an extremist approved on the court. And so what happened is Mitch McConnell bent the rule and really upset the partisan balance of power. And I say this because, the Republicans now have an additional seat on the Supreme Court that technically they're not supposed to have. They have it because Mitch McConnell bent that rule in the last year of the Obama presidency.

And then when Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed in the last year of the Trump presidency, all of the Republicans who said use the excuse that they wouldn't confirm they, the made up rule, that they wouldn't confirm a Supreme Court justice in that final year. They all scrambled and confirmed Amy Coney Barrett within weeks of an election. So forget an election year, within weeks of an election, they completely did a 180 on their reasoning.

And I bring this up because I think that the Supreme Court, which is, you know, it's packed, meaning it's, not it's not legitimate in its numbers. Right. And its ideal, it's ideological balance does not reflect well, it's out of step with the American public. Right. So for the first time in, in US history, we actually have a, minority court, meaning that they're, they're, out of step with most, major public opinion, whether it's the environment, whether it's voting rights, whether it's abortion, whether it's gay rights.

This particular court has been packed and they're out of line, out of sync with the American public. And I think that they are likely to uphold a lot of these state's decisions to roll back voting rights. For example, there is the Arizona case, which was heard before the Supreme Court last week. Arizona has passed a number of restrictions that on voting that disproportionately affect Native Americans and disproportionately affect Latinx Americans, both of whom are more likely to vote Democratic.

And these are Republicans who have pushed these laws. And what was interesting is during the hearing, Amy Coney Barrett, the newest Supreme Court justice, actually pushed the Republican Party of Arizona and said, why are you here? Right? Like, why are you testifying about this? And the representative from the state party said, oh, well, because it affect, it benefits our party.

It affects the partisan balance in the state. So he was very open about the partisan nature of, of essentially eroding our democracy in the name of winning elections. And yet I think the Supreme Court will likely uphold all of this because I think they're they're pretty out of step because of the rule bending with Mitch McConnell. And I actually will just say on the filibuster, I don't think getting rid of the filibuster is going to make things better.

It'll swing it to the Democrats for right now, and then the Republicans will get in power, and they'll pass legislation that the Democrats don't like. So that this idea that the Senate has to work together, is is going to be gone probably within the next year.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Well, those are powerful points. And I would just add, a couple of others, I think that the Congress needs to exercise its full authority under the elections clause of the Constitution found in article one, section four, which provides that, in fact, the time, place and manner of election shall be regulated by states except Congress is free to alter and essentially override those decisions except with respect, except with respect to the places, where those elections will be held. Indicating ironically, to those who today are arguing that states should have full authority to regulate elections and that any congressional effort to pass legislation to override the state efforts, constitute an invasion of

states rights are, are saying that without merit, because the Founding Fathers wrote that clause making the final placing, the final decision making authority in the hands of Congress. And so I think, Caroline, it's imperative for Congress in the name of democracy, in the name of voting rights to, in fact, exercise that authority and pass H.R.1, now S.R.1, in front of the Senate, because if it does not, then I think the future of democracy, through the future of voting rights is very, very grim.

And that's why I think that there will be great pressure, to abandon the filibuster, because without it, all of the possible protections for voting rights will fall by the wayside. Because of your astute point, I think that, the court is likely to uphold those state laws. So if Democrats don't act now to exercise the power that they enjoy by the slimmest of slim margins.

Not only will they rue the day that they, failed to act, but America will pay a terrible price. And when, and I'm glad you mentioned Mitch McConnell, because he did carve out an exception to the filibuster, so that it didn't apply to Supreme Court nominations made it easy, as you point out, to pack the court, in a historically, untenable method.

And today, when he threatens, a scorched earth policy in the Senate if the Democrats should drop the filibuster, that's what you would expect of him, because as leader of the party trying to suppress the vote, what would we expect him to say? He doesn't want Congress to exercise its full authority. So I think in the as a democratic imperative, and in my view, even as a moral imperative, it's important for and I see we have a very important audience.

Member.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: This is Dora. She agrees with you. Doctor Adler.

Dr. David Gray Adler: I appreciate that. That's good to have. We they have one, one supportive voice. So I think in the name of democracy and as a as a moral imperative, as I say, Congress must act. Otherwise, we will see a very large number of American people, people of color, largely, denied their voting rights. And, and one more point on that.

And maybe we even have some questions here soon. But, one more point. When I hear state legislators saying, the voting should not be easy, I'm so perplexed. The Senate majority leader here in Idaho and a couple of weeks ago was quoted in some news stories, because he introduced a bill that would deny, people the right to bring more than, return more than one ballot, because he, he feared voter fraud, which we've had like none in Idaho.

He said voting. So what? That means you've got to make two trips to the post office one day, pick up your ballot, another to mail in. And he said, quote, voting shouldn't be easy. But again, why shouldn't it be easy if we truly believe in democracy? And I repeat myself in saying that it's important for citizens to understand that state legislatures across the country, which are enacting these voter repression laws in the name of non-existent fraud, are doing so to exalt their power over and above, the principles of democracy.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: I couldn't agree more, David. And also just, you know, it sounds like we're being alarmist, but at what point do you blow the whistle on one person, one vote, you know, do you do you blow the whistle when, you know, when all of a sudden, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is gutted and you see a slew immediately see a slew of laws put into place to make voting harder.

And all of a sudden, you see a decline and a disenfranchisement of black voters, of Latinx voters, of Native American voters, of older voters. At what point do you blow the whistle? You certainly blow the whistle. You know, when you have, 44 states doing this right now, capitalizing on the the big lie, right, that the the 2020 election was fraudulent.

That is a big lie. It's a demonstrable lie. What I and I just really do to to stress this point and, and bring it home, we, if your political party is contingent upon keeping people from the polls, you need to rethink your party platform. If your party has become the party of white ethno nationalism, and because of that, it's only appealing to a fraction of the population,

you've got to shift your policy agenda. You must widen your tent. It's not so set partisanship aside. It's actually not sustainable for voter disenfranchisement to be the way that the Republican Party moves forward. They have to get a bigger tent. They have to appeal to more people. So using these more narrow appeals and kind of entrenching as as Donald Trump did has profoundly harmed the Republican Party.

And I would love to see how they reinvent themselves so that they don't have to disenfranchise voters, but rather will inspire voters to go to the polls as a way of winning elections.

Dr. David Gray Adler: I, I agree, I think the, the failure to, to adopt or to create a broader tent so as to bring in, voters that might enable them to win future elections is, in fact, a, is exactly why they're trying to suppress votes. I'm reminded as by way of analog to to your point about why James Madison opposed, any state aid to religions.

Because he said if a religion requires aid from the state, it shows a failure on the part of that religion to appeal to potential parishioners. And they either need to change their approach and their doctrines, or they need to get out of the business, but they should not rely upon state assistance. So, here it's pretty clear, what the incentive and the motivation, frankly, are on the on behalf of the Republicans.

And to your point, on the very day that the Supreme Court rendered, the very shameful decision in Shelby County, Texas, the state of Texas legislature passed a voter suppression law that evening, meaning that those states were ready. They were poised to, to get into action. And it's very sad because we've seen that the very valuable, protections, provided by, the Voting Rights Act under section five, which required, state communities or states which, had demonstrated a pattern of raceism, had to receive, preclearance from the Justice Department before they could revamp their election laws,

were, were stymied by that statute until the court dropped it. And then, as you say, some three dozen states moved very quickly, to enact suppression laws. So it's a critical time. And you ask, when should we blow the whistle if you don't blow it before, the storm comes, then it's too late. Doug, do we have questions?

Doug Exton: We do. So the first question is from Walt, and they say it seems like at least one Democratic senator will not go along with any attempt to rid of the filibuster. What do we do about that?

Dr. David Gray Adler: What do you think, Caroline? What's your response?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: So I have a moral response, which is that I don't want to get rid of the filibuster. My moral response is, I don't think the answer to the scorched earth, rule bending policies of Mitch McConnell is to engage in the same behavior. And even though I know it would be very painful, and I know that for Democrats who are in power now to not be able to pass major legislation during a period of time when there's not a lot of bipartisanship, and I'm even convinced that when Republicans take the reins of power again in the Senate, that they might do away with the filibuster because everything is just two sided, you know, talking out both

sides of your mouth. Nothing. And Mitch McConnell, no words that are coming from our political leaders, mouth mouths in the Senate mean anything. So Mitch McConnell saying he won't get, you know, he won't get rid of the filibuster now and standing against it means nothing if he gets into power and then decides to do that in a few years.

But my thought is that I don't want extreme government. I actually want to return to some form of bipartisanship. And I assume, you know, Dianne Feinstein has come out and talked about the importance of maintaining the filibuster. And she was ridiculed during Amy Coney Barrett's hearing because she hugged, you know, Senator Lindsey Graham from across the Partisan aisle.

And I, I'm not being naive here. Like, oh, everyone should hold hands and sing Kumbaya. But I actually don't know where this ends. If we keep bending the rules and getting rid of these institutions and the institutional rules that we've had to hold us in place, I think we've just been through four years of Donald Trump taking the rules and norms of the presidency and bending them every which way.

And I don't think that that's the answer. And I wish there was something else that we could do here to appeal to the better angels of Republican leadership to say, look, and maybe I'm being naive, but but you shouldn't be placing party power over democracy.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Well, the other side, of course, is that the filibuster was not part of the Constitution. It was created much later in our history and often, as you well know, was exercised by Southerners to maintain segregation. And so it was used in an immoral way. So maybe it's the case that by abandoning the filibuster, we have the opportunity to actually promote a greater morality in it in the context of democracy, by empowering the majority, duly elected by the American people, to promote their own version of what constitutes the general welfare writ large.

And I think you're right to point out that we would not know what, Mitch McConnell and the Republicans might do, when when they do regain power. But isn't it interesting to contemplate how to respond to a Senate leader, in this case now, the minority leader who has no interest in maintaining traditions and processes? Allegedly so near and dear to his heart, which is frankly preposterous because he's willing to violate all the norms and traditions to, to achieve his ends.

How to handle somebody like that? Is there an overriding? I'm glad you raised that great ethical question. Is there an overriding concern to, to abide by rules which in the end, would undermine the Democrats' ability to pass landmark legislation and make much necessary reform and to achieve goals, which, frankly, will serve the great interests of those who have been underserved and ignored for so many years.

It reminds me of some of the classical, Platonic dialogs on how do you treat your opponent when your opponent doesn't play by the rules? Great subject for debate in the classroom that you and I have asked our students to participate in many times. And that's a great question, isn't that?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: And there is no answer. There's no right answer. I think the point you made about, like, maybe you've been the rule this time in order to save democracy, I mean, maybe, maybe that is that's an ethical. Yes. Yeah, it's hard to say.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Or maybe you don't even have to say that we're going to bend the rule to save democracy because programs, policies and laws are changed all the time. And really, hasn't that quote unquote rule already been bent, seven ways from Sunday? If isn't that some old phrase or maybe it's eight ways from Sunday? I don't know. This is Thursday.

I'm not even there yet. That was a great question. What a thought provoking question from Walt, that's terrific.

Doug Exton: And the next question we have is from Donald. And they ask, is it accurate to characterize all 250 plus bills filed in state legislatures as voter suppression? Can there be any changes in voting procedures that would be meritorious or at least non objectionable?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: So yes, absolutely. So I should say that the 250 plus, bills that have been deemed voter suppression have been deemed so by the Brennan Center for justice. So there are actually more than 250 bills that pertain to voting that have been proposed. But these specific bills are about rolling back, making it more difficult to vote.

So are there things that I would endorse ethically? Absolutely. Anything that makes voting easier would be laws that I would endorse, but also in terms of of the voter suppression laws, we have pressing issues, right? We're in a global pandemic. We have folks experiencing homelessness, who are houseless at very high rates. We have racial injustice.

We have major problems in our society that need to be addressed. So why are state legislatures spending time and energy and money on passing laws that address something where there is no problem. So it's objectionable from many different standpoints. One from a you know, taxpayer standpoint that I don't want to fund bills that suppress the vote and don't do anything to improve democracy and do not address the problem.

But two, I definitely don't want to support any bills, you know, on moral grounds that make it more difficult to engage in the most fundamental right of our of our country, which is voting.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Yeah. And you're and and by the way, and since people in, in the audience often ask, where should we look for, reliable information? The Brennan Center for Justice is reliable for all of you who wonder where you can turn to valuable information and insights and analysis about these bills, go to the Brennan Center for Justice.

Excellent. And, it's got a great reputation.

Doug Exton: The next question from.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Oh, I'm sorry. Go ahead. Doug. Oh.

Doug Exton: Yes. The next question from Theresa is with the, the moves of so many states to suppress the vote, do you see any chance that those actions can be subsequently rolled back? You know, more towards the lens of, you know, easier access to voting?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: If H.R.1 passes and, the Senate and it passes in the Senate, so. Well, it's passed in the House. If the filibuster is removed, it'll pass in the Senate and then it'll go to the states and will be tied up in court, probably for the next decade, with a conservative Supreme Court that is likely to uphold states pushing back against H.R.1.

Right. So I would say maybe a little bit of hope that there would be some positive movement on this. But again, the Supreme Court, we've we have a packed court for the next three decades. It's going to be it's going to make national politics look differently than, than a democratically elected government.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Yeah, it's a really good question. I think if if Congress were to pass H.R.1 and, Congress exercises its full authority to govern the time, place and manner, of these elections, then the court would be hard pressed to strike down these measures because it's not the classic case of asking, is this a federal or state authority?

Because the plain text of article one, section four, makes it, very clear that Congress has the ultimate authority. That in this case, the framers to the Constitution were weighing in on the side of federal authority, not state authority, a point which would tie advocates of states rights in, many, many knots. Uncomfortable.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: David is more optimistic than I am. That's a good thing. That's a very good sign.

Dr. David Gray Adler: It doesn't cost any more to be optimistic.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Right.

Doug Exton: Then what is the role that gerrymandering plays into voter suppression and voter apathy as well?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: One important aspect of H.R.1 that I didn't mention was that it would establish nonpartisan commissions to set up the boundaries for various voting districts. So gerrymandering is where you get these districts that look like little snakes or dragons. I mean, they're very cute. But they're also very specifically drawn so that they can, make a district, a Republican district or a Democratic district.

And what happened, in California, about a decade ago, is Arnold Schwarzenegger the recall election, right. He he, our first recall election, he replaces gray Davis gets in and all of a sudden acts like a centrist Democrat and says, look, we're going to have nonpartisan redistricting in this state. And so we establish that commission, and all of a sudden our elections became more competitive.

Why? Because the districts were drawn in a way that didn't particularly benefit one party or another. They weren't drawn in a way in order to limit, for example, and marginalize Republican voting in the state of California. And most states, have partisan commissions, and so they draw the districts to benefit whatever party happens to have the majority on that commission.

So that's a really long way of saying if H.R.1 passes, which it may, that it would actually address gerrymandering, and that would be an important step toward actually having better representation.

Dr. David Gray Adler: I agree that would be a very healthy point for democracy. And I'm reminded of the fact that just a few years ago, a ballot initiative in the state of Arizona was passed, which in fact transferred, redistricting from the legislature to an independent commission of the very kind that Caroline mentions is embodied in H.R.1. The state of Arizona.

legislature came to the Supreme Court and wanted the court to strike down, the ballot initiative. And the court ruled against the legislature, saying, in effect, that when the Constitution provides that, state state legislatures may in fact make the decision regarding time, place and manner of elections, it's referring to the law making body, which, in the case of a ballot initiative, is the people, the people, as a, as a collective whole.

And so that's healthy because that tells us, that if, there are more lawsuits, that in fact, the the court could follow a very recent precedent and uphold, the efforts to render these, commissions independent, free of the very kind of partisan politics that Caroline mentions.

Doug Exton: And taking more of a local spin on things. Caroline, with the graph you showed, it definitely showed that uptick for 2020. But I also know there is sometimes a trend of just doing the presidential vote and then not even looking at the rest of your ballot, just handing it in, going home. Do you know, with 2020, was there that trend still kind of a thing, or was there still a lot of interaction with the local down ballot measures?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: That's a great question. So, that happens, as you noted, Doug, in every election, it happened more so in the presidential election, and specifically it happened on the Democratic side. So there was a larger pattern than we've seen in modern, you know, in the modern era of politics, a larger pattern of Democrats going in. And just for the folks going in and just voting for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.

Right. Just voting for that ticket and not voting further down the ballot. But, David, perhaps you have more information about what happened in Idaho.

Dr. David Gray Adler: No, I think that what you say applies to Idaho and across the nation. And I wanted to turn on that a little bit, to direct our conversation for a second to the problem of apathy. Even though we had a great turnout in the 2020 election across the nation and in here in Idaho specifically, 81% of the voters turned out a record and more voters than ever used, mail in ballot or absentee ballots.

We still see across the nation, the fact that, what, 48% or so of the American people choose not to vote. How do you explain that problem of apathy when so much is on the line?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Well, I wrote some, chapters of my dissertation on this, this idea that, and I'm chuckling because it, it just it's a depressing but it holds true even many years later, having looked at this, that, that, we had so we used to have what I call a producer, approach to citizenship. Right. So producer citizen. So the, the call, the clarion call.

Right. Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country. Right. Turn that on its head. We see the rise of consumerism in the 60s and 70s, which shifted the ways in which we view our relationships to government, view our relationships to other human beings, view our relationships to institutions. So instead of asking, you know what you can do for your country, we ask our the standard is to ask what our government and everyone else can do for us.

It's we are much more self-focused as a country and it sounds like I'm wagging my moral finger. It's not so much that I mind the shift in the brand of human being, if you will. It's what it's done to democracy. And so, the very first thing that I do with my students is, you know, in my one on one classes, I say, how has government affected you today?

And it they're hard pressed to think about ways. And I'm like, well, did you brush your teeth? Did you die from the toothpaste? No, the FDA. Did you hop on the road? Did your car, you know, did your tire get punctured? No, because the roads were maintained and you were able to stop at stop signs and, you know, just going through all the basic things, you were able to breathe the air, especially in Los Angeles.

Right? Our air quality is much better than it was in the 70s and 80s. And so this, this idea that government doesn't affect our lives, I think that's a pretty common thing. Another thing that that, comes along with consumer citizenship, and perhaps the failings of the moral failings of our leaders, which it's hard to say because they've always kind of failed us.

So it's not like it's worse today than it was during the Teapot Dome scandal 100 years ago. But this idea that, you know, Americans have low political efficacy, which is the belief that their voice matters in politics. So I think we have a really hard time seeing how government affects our lives, because we are very self-focused and don't view ourselves as part of a community that has to contribute to a broader culture and a broader citizenry and a broader democracy.

And also, you know, we don't think our voice matters that much. And this is especially pronounced with more marginalized Americans. So, people of color, transgender Americans, women, there's this idea that our voices matter less because we have less social standing in the world. That translates into how we interact with politics. So, yeah, David, apathy is still a really big issue.

And I wish we could, you know, wave a magic wand and get folks thinking about themselves as contributing members of a democracy.

Dr. David Gray Adler: And, you know, isn't it interesting, Caroline, you and I both live in states, in which a large number of voters believe that their voice is irrelevant. It doesn't matter. Republicans in your state of California, Democrats and here in Idaho. And so how do we try to persuade people, to participate in politics when they're so vastly outnumbered by the majority party?

That's that's a tough road to hoe. Yeah.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Yeah, it surely is. I mean, what we saw in 2020 is, a lot of people were voting against rather than voting for. So that getting back to that question you asked Doug about the phenomenon of people going in and just voting for the presidency. A shocking number. Were just doing that for Biden. And I initially said, oh, Democrats were doing that.

It wasn't just Democrats. And it was voting against. Right. There was a big push to vote against. So the more lightning rod candidates you can, put into office who folks want to vote against. I mean, that's how we increase participation, which is really a sad statement. Right?

Dr. David Gray Adler: And isn't isn't it the case, Caroline, that disenfranchisement is perpetuated by the Electoral College. It would be different in your state and mine, at least people in the minority party could feel as though they were contributing and participating. If we had a direct popular vote for the presidency, right?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Absolutely. I mean, the Electoral College was put into place to give slave owning states more of a vote and to maintain their power in the Congress. We know the history of it is, you know, very problematic and racist. Today you're right that it functions. So for folks who are unfamiliar with the Electoral College, the presidential election isn't really a popular election.

It's not even a national election. It's election a it's an election of 50 states, 48 of which if you get 50% plus one vote, you get the entire slate and the Electoral College or Maine and Nebraska are exceptions to that. And by and large, they shake out to be, you know, a winner take all situation to. And so, yeah, why would a Republican in California, in California it's 2 to 1 Democrats over Republicans.

Republicans. Why would what's your incentive to go to the polls? What's the incentive to go to the presidential polls in Idaho? So if we made it really, truly a national referendum, we would have a set of issues that would arise, mainly that presidential candidates would hop between like Philly and New York and LA. Right. Maybe with a stop in Chicago and maybe one in Atlanta, but it would just be kind of a big city swing.

But you're right, David, that at least people would feel like their vote mattered.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Every vote within count, every vote would count. Which would be the goal in a democracy, right? One person, one vote in a different context. Doug, do we have a few more questions?

Doug Exton: We do. Ingrid asks, how can the legislators decrease opportunity for citizen initiatives?

Dr. David Gray Adler: To decrease or increase.

Doug Exton: To, that just says decrease. So we'll move on to another question, give Ingrid a chance to clarify a little bit. How can we protect the vote from partisan groups like the IFF that influences the legislators?

Dr. David Gray Adler: Well, legislatures across the country are trying to make it more and more difficult for people to act as lawmakers through ballot initiatives. That's the case here in Idaho, as as the questioner may have, may have addressed, and one of those reasons, one of the reasons for legislatures making it more difficult is they're able to concentrate power in their own hands.

And then, for example, in a state like Idaho, where a ballot initiative last time out, nearly made it to the ballot, and that would, that was to approve, that was to approve recreational use of marijuana, which rankled the powers in the legislature. And I think that's a major reason why the legislature in this very session has a draconian, bill before it that would make it very, very difficult, for ballot initiatives to, be successful, to even make it to the ballot, I should say, and then be successful.

Maybe, maybe that's the case. But California's a case where there's a state where there's a lot of initiatives, right? You you all in California like to exercise your lawmaking power, right, Doctor Heldman?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Well, yeah, we'll call them citizen initiatives in quotes,right. Because the average amount that it takes to get a citizen initiative on the ballot is $12 million. So it means it's not really coming from citizens. By and large, our citizen initiatives are it it's but it's, interest groups, mostly corporate interest groups kind of manipulating, public, the public to pass things that the legislature won't pass.

And I know I'm being too simplistic about that, but unfortunately, I don't know of a state that has a true citizen initiative process. I would love to see one. And I think they're, you know, they're wonderful. They're a way for citizens to enact policy directly when the legislature is not responsive. Right. It's another check on government.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Here again, just very quickly, Doug. The even though the Idaho Legislature is attempting to make it very difficult, to move forward with citizen initiatives or ballot initiatives there, again, they would be surprised to learn that the founders of our nation, we're we're we're embracing the concept of citizen initiatives. They called them out of doors conventions, out of doors conventions.

Another factoid, for those who advocate states rights to realize they're running, they're swimming upstream against the current established by the framers.

Doug Exton: And it looks like the last question that we all have time for tonight is who is still excluded from voting?

Dr. Caroline Heldman: Well, felons, are excluded from voting in I believe it's still 19 states. And that disproportionately affects, black people, black men in particular and Latinx Americans. I wish that, you know, if I had a magic wand, I would get rid of that. I mean, what better way of feeling like you are part of the the country, part of the citizenry, part of your state, your locality, then casting a vote?

Once you, you know, have, been released from prison, I can't imagine a better way to inculturate somebody's back into a community than through exercising your basic democratic right. And yet, in almost half the states in the union, we restrict that. That's the only voting. I mean, obviously, if you're not a citizen, you can't vote. There are groups that are disproportionately affected by all of these laws.

Right. And we've mentioned, people of color, certainly transgender individuals, students also in some parts, because they're in different parts of the country. Right. And they've got their student IDs, but then their, their state IDs are from different states, like in the state of Texas. You can vote with your, your, your gun permit, but you can't vote with your student.

ID, think about that for a minute. So there, there are definitely folks who are disproportion affected by this. And then older Americans. Right. How discrimination. If you are no longer driving, why would you need a license? And if your licenses are not to date in some states you can't vote.

Dr. David Gray Adler: I think that's well-said. And so the real question now is not merely who is prohibited from voting, but in fact, who might be, in a find themselves in a very difficult position and unable to exercise their fundamental right to vote. You know, I'm always reminded that Aristotle, who was the great Athenian champion of democracy, said, democracy is a system in which we try to spread political power as widely as possible.

That's not what state legislatures are doing across the country. It's not what Mitch McConnell and his colleagues in the Republican Party are doing. They are acting in a fundamentally undemocratic way to make voting difficult and to concentrate governmental power in the hands of those who do not favor democracy.

Doug Exton: Well said. And unfortunately, that is all the time we have for tonight. So thank you to everyone for attending. And thank you to both of you for such a wonderful and engaging conversation today.

Dr. David Gray Adler: Great to be with you and always a joy to share the podium with my colleague and friend, Doctor Caroline Heldman. Good to see you, Caroline.

Dr. Caroline Heldman: It's good to see you, Doctor Adler. And thank you, Doug, for hosting us. This was a wonderful conversation.