Chelsee Boehm; Lester Taylor; Henry Whiting

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

David Pettyjohn: Greetings everyone. My name is David Pettyjohn. I am the executive director of the Idaho Humanities Council. I want to thank each of you for joining us this evening for another one of our connected conversations. Before I kind of introduce our speakers, I would like to, first of all, remind each of you that, we will have a question and answer session.

So we'd like to to remind you that this is just one of the many programs that we offer here at the Idaho Humanities Council. And if you're not familiar with our work, I encourage you to go to our website, which is Idaho humanities.org. So tonight we are, going to learn about Archie Boyd Teater, art, architecture, artifacts and archives.

What a name. And joining us tonight is Chelsee Boehm, Lester Taylor and Henry Whiting. And they'll each say a little bit about themselves. So I will now turn it over to Chelsee. Welcome, everybody.

Chelsee Boehm: Thank you. David. I'm Chelsee. I am a public historian. I currently work for the Idaho State Historical Society, at the Idaho State Museum.

Lester Taylor: And we. Why don't you start?

Henry Whiting: Well, I'm Henry Whiting. I am the owner of Teater's home. And I'm looking forward to, to talking to everybody. I'll introduce myself more, more comprehensively and a little bit when I get started here.

Lester Taylor: Okay. I'm Lester Taylor, and I don't know whether you're supposed to do it this way or not, but I'm talking to you from my library in Tucson, Arizona, and, although I, I have written a book about, art, but I'm not an artist. I'm an art historian, and I not critic. I'm an economist. And I look forward to talking with Henry and Chelsee about art.

And these are all right.

David Pettyjohn: Thank you all very much. So, Chelsee, I think, we'll kind of turn it over to you now to kind of lead the, the discussion.

Chelsee Boehm: Thank you. So, yeah, I'm Chelsee, I am presenting this evening. I'm participating this evening from Boise, which is the ancestral homeland of the Shoshone Bannock people. So before we begin, I want to pay my respects to the members of that tribe, both past and present. So a little bit of of a summary about how tonight's gonna go.

I am going to turn the time over first to Lester, and he's going to tell us about, Rita's life and his art. And then Henry is going to talk about two years now, and then I will follow up at the end with just a brief bit about the archival collection. The writer, the Archie Boyd Teater archival collection at the Idaho State Archives.

And some of the artifacts at the Idaho State Museum. So let me share my screen. Oh, can I have permission to share my screen? So, Lester, to begin. Can you tell us a little bit about Archie and his early life?

Lester Taylor: Certainly. Thanks, Chelsee. Archie was born in 19 oh, and, in Boise. And he grew up, in southeastern Idaho, much of it in, and Boise and a lot of it also in the Hagerman Valley of, along the state route. And in this slide, we see Archie's, father, Peter Boyd Teater and his mother met, meditated.

And it there were five, five children, two boys and two girls. And in this slide, we have Archie, and his two brothers. Archie is the one, in the center there. And, it might is his, schooling years in Boise and, and much of his teenage years he grew from there is along the snake River in the Higgins Valley.

And, he the family was and was in general a very poor one. And Archie didn't get to really didn't get to eighth grade. But, it as he put it, he was requested to leave eighth grade because he was doodling rather than doing his mathematics. And at a very early age, and he's, probably 12, 13 years old.

He's, he, artist one time that was in a, I guess they called him a book. I just, in, drugstore in Boise. And he was painting portraits and other things. And Archie decided right then in there that he wanted to become rock. But in his teenage years, he spent much of his time, working in logging camps and, in Idaho or.

Excuse me. And, or he could. And along the snake River, in mining, gold mining camps, in the Higgins and. Well, and he started painting, in his teens. But he didn't have any formal art instruction until, 1921, when he went to, went to the Portland Art Museum. Important. And in this slide, he chose the, picture of the, in Portland at, at that time.

And he spent, two winters, studying art for the Portland Art Museum. And then, he came back to Boise and in, the years, say 1922 to 1928, he spent most of the summers, during those years, in the Sawtooth Mountains, in Idaho. And he would, he would start this summer by working with, with, to, to burros, up to the Sawtooth and spend the summer in Sawtooth, trekking about and painting, in 1928.

He oh, this is an interesting slide because this shows him when in the in the, sometime in the 1920s, in his stone dugout that he dug, which actually is, and Henry can correct me on this, Henry took me down to, to this site, several years ago. It's probably about a mile or so from, in, from Peters Mill.

And this is kind of what was left from, from Teater's, dugout, on the bank of the, of the, of the snake River. And the only thing that's left in it other than the rocks is that, is that iron door from, from his stove. But, then in the 1928 first went to Jackson Hole and where he spent summers for essentially the next 50 years, in, in this painting and the Tetons, like in Jackson Hole.

Archie was, an enormously prolific, artist. I can personally account for the whereabouts, obviously not my, my own paintings, although I do have a number of upwards of 4000 of his paintings. And my estimate is that he did at least, double that quantity of the order of the eight, 8000 paintings. This is a painting that we're looking at now.

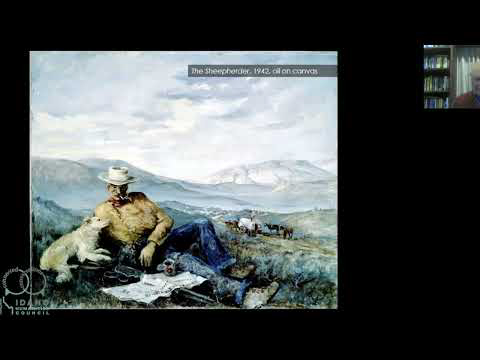

This is a painting that was done in Hagerman Valley. They wanted, the house in a water wheel and, he did, many, many of his paintings were done in the, in The Hagerman Valley. But also a great, number of them were, done. And they sought to this, this this painting here, was done in 1941, just shortly after Pearl Harbor.

And it shows it's called the sheepherder, and his dog. And it probably is just it's a generic setting, probably in the Hawaiki, plateau or in the, in the white Hawaii and very south, southwestern Idaho. This is, a number of, another of, a very typical, type of painting that, it did of Idaho.

This is his starting school. But you catch him, catch him. Idaho. And it was painted probably about 1935 to 1937. And then, and another of his paintings, I think they should be coming up. The, Oh, yes. This is, this is one of my favorites. It actually was the, the, wedding invitation for my daughter's wedding, and back in 2001.

And it's Dance at Slaveys, which, this was a, it was a bar. And, Ketchum that was extremely popular in the 1930s. And the. You will notice the, up at the top, the mermaid, that it actually did that painting and it hung in the, in the slaves for many, many years. And I personally have been trying to locate that painting for a number of years, but so, so far with that and with that success, then there should be a painting coming up.

This is, that they chose this sought to use this is an old Stanley, kind of what old Stanley looked like, almost certainly in the early 1930s. And this is a north end of this sawtooth. Then there should be a painting that, that, that shows, this was entitled Dust Storm. Another fairly typical, type of, painting that he did.

And this probably is in an area fairly close to King Hill, east of, east of Boise. Probably not too far away from, well, now seeing the mountains in the background, is probably more of a generic painting, but, then another painting that I certainly went to, should be here is, is a looking kind in 1967, in the winter of 1967, it took it upon himself to paint, upwards of two dozen or more of, of, primarily, yeah.

Mining scenes. But he also did this painting of a logging camp. This would be typical of the logging camps that he worked in, when he was a teenager in, in Idaho. And he made an effort in this painting to show essentially everything that went on. Yeah. That was used in terms of, what went on and in terms of the tools and, and the like that, that, in like in camps.

And I think next, should be a, this is one of the upwards of two dozen, mining scenes, mines and mining services that you did in 1967. And the purpose of this was to, was to capture, what, mining in the 19 in the teens, 19 in the teens and early 1920s of what mining, was like in southern Idaho.

And these paintings were extremely good resource for the history of, of mining in, early history of mining in Idaho. Then I think there should be coming up a slide. And this is a mining camp. This is what, a generic, painting of, mining, of a mining camp along the Snake River and Hagerman Valley what it was like in the in the teens, valleys between 1910, in 1920.

And this is actually a very autobiographical painting because in the middle of the snake, you will see that there is a boat and, that really is, Jesus father, and his brothers and they are capturing, what was then just absolutely gigantic, sturgeon and the sturgeon. The sturgeon who is then, caught and then in, over, toward the left, side of the painting, you will see a wagon with sturgeon in the back.

It has itself has put himself in the wagon. And the sturgeon were then subsequently, sold to the mining camp for food for the miners. Now I see the next, next painting. We jump to Jackson Hole. And in 1928, Archie made his first visit to Jackson Hole. Yeah. A, and the, Ford, I'm not sure whether it was a model T or a model A, I think it was a play.

And, that was 1928 as he made his first visit and he subsequently, then spent virtually every summer, for the next 15 years in, in Jackson Hole. And during much of the latter part of that, he, he had, his own, studio there and he, among other things, he, painted many, many, Jackson Town scenes.

And the title of this would be Jackson on, Jackson on that Saturday night. And, this is for those of you that know Jackson. This is now Broadway. This is Broadway running through the, into Jackson, looking into the south side of the, of the Jackson County square. Okay. And this is just a fairly typical, genre scene of, Archies.

In. The the slide just before this can get to go back to that, Chelsee, this is one of, Archie's, probably, for locals in Jackson, in Jackson Hole is probably, one of the, of his best known paintings. It, was for years in the Jackson drugstore, and I'm happy to say it is back in the, Jackson drugstore now, although it's not a drugstore, it's, it is a restaurant, but it shows during World War two, when it was decided that, that, the government did not want to, to feed so many elk, you know, in the wintertime, there was an elk massacre.

And this is Archie's painting. Painting, so to speak, what he called the Elk Massacre. What's next, Chelsee?

Chelsee Boehm: So, Lester, we're getting a little tight on time. Is there something you want me to jump to? That you want to make sure that folks see or.

Lester Taylor: Okay, quickly. This, this is showing. Okay. Those of you that know the movie. Shane Shane was shot in Jackson Hole. This is the frontier town. Then, in Shane, this is, is another, century genre painting. This is showing, that, the Mormon settlers along Mormon Road in Jackson Hole, keeping the elk out of their ....

And this is, this shows, Archie's whimsical, side, his really fun side. One Saturday night, he was out for a walk, and there were, two, ladies from the cowboy bar. They got into a fight. They took the fight out into the, into the Jackson town square. And this is just this Okies.

Painting of this, maybe we can save. Oh. I gotta say about this, as I mentioned, Archie had two winters of, of, training at the Portland Art Museum in the mid 1930s. He studied for two winters at the end and, Art Students League in New York. And again, he did studied there at during World War Two.

Winters in 1938, he did this painting of, what, southern Manhattan look like. And that's the Brooklyn Bridge. And and why we can save other things till later. Chelsee.

Chelsee Boehm: Okay. Are there any that you want to make sure that you talk about or. I'm just flipping through really quickly? Archie traveled the world and got to paint in a lot of places, so that's kind of what I skim over.

Lester Taylor: Okay. Back up to, One more. One back up. Okay. He loved parrots and it in that. Starting in 1958, Archie and Patricia traveled to more than 100 countries and they spent, much the winter, for the last 20 years. He lives in those 100 countries, more than 100 countries. Archie painted every room. And there was, there's the sand, nighttime on the sand, which, Kabul, in Afghanistan.

That's the nighttime, the longest on the sand. And this is Kabul in Afghanistan. And I think the next one is the upper house in, Sydney. Then I'll keep the rest to later. Thank you. Chelsee.

Chelsee Boehm: So are we. Are we going to turn it over to Henry now?

Lester Taylor: Oh, yes, by all means.

Chelsee Boehm: Okay. I'm going to stop sharing my screen for a second so Henry can talk a little bit about himself and how he kind of got to. There's no. Yeah. Henry, whenever you're ready.

Henry Whiting: Okay. Can you see me now? All right. Welcome to Teaters. No, all. I'm sitting at the dining room table here as as I, talking to you. I first learned of the Teater Studio in 1974, when I was in college, from a book called The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright by William Allen Store. It was the first book published that had photographs of all of Wright's extant work, including the Teater Studio.

I was born and raised in Midland, Michigan, where my great uncle Alden Dow had designed our house and over 100 buildings in the town of three of 30,000 residents. Alden was a student of Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1933, the first year of Wright's Taliesin Fellowship, a school for young architects. Alden was my close friend and mentor until his death in 1983.

The Teater studio was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1952. At the same time he was working on the Guggenheim Museum in New York. He was certainly America's most famous architect at this time, and it's hard to imagine an architect of his stature today if there even was one. Taking on a job as small as an 1800 square foot, one room artist studio in rural Idaho, for which he was eventually paid $1,500 in the spring of 1968.

Our our family first came to Sun Valley for a ski vacation. We all loved it immediately as it got us out of dreary Michigan winters and into the sun. We came back every spring for ten years until my parents retired to Sun Valley, and I moved there as well to help with the design and construction of their house.

Because of my interest in Wright, I immediately sought out the Teater studio, which I first saw in 1977. When I purchased the studio in 1982, I knew of it only through the connection of Frank with Frank Lloyd Wright. It has been one of the great joys of my life to learn about Archie and Patricia Teater through their friends and acquaintances, as well as the documents found at Teaters Knoll.

Okay, could we go to the first slide? The.

This is a photograph of of Teater home that was taken. Just as it was nearing completion. And it gives you an idea of the site. This was probably taken in about 1957 or 58. I'm going to I'm going to guess, and you can see the snake River beyond and above the studio and, its site at the lower end of the Hagerman Valley, and the road that runs in front of it was old highway 30, which at the time of the construction of the Teater Studio, was the main East-West road in southern Idaho.

And over the past, however many years, that really hasn't changed much, except it has probably less traffic now. Okay, next slide. This is a little bit closer view. Taken a little bit later that shows the studio from from the south and you see those little trees that are just above the retaining wall. Those have now grown to be about 40ft tall.

And the whole, studio is the whole property at Teaters. And all this all has mature, vegetation all around. The river is on the left hand side below that wall. There's a 200ft cliff that leads straight down to the river plain. And then the river is perhaps a quarter mile away. Next slide. This is a picture of Archie sitting on his on his patio wall.

With, with the studio nearly complete. And I'm guessing that all of that rock that you can see piled up is going to be the, flagstone patio that they built. Now, what's important to notice in this picture are the windows of the main studio room behind Archie's back, and how the window sills slope parallel to the to the, plane of the roof.

They are not horizontal, and that has quite a profound effect when you get inside the studio. The higher roof, the clear, starry roof. And above Archie, is is where the bathroom and the kitchen are, as well as the small, storage, workshop. And the high masonry is, is the fireplace chimney. Next slide.

This is the inside of the studio as it looked when the Teaters, lived there. And those three chairs that you see in the middle are the dining room chairs that have been moved to create a little bit of a, scene here, a little arrangement. And you see the paintings up on the, above there. I believe that the big one might be Custer's Last Stand, but lest we'd have to, confirm that.

But their collection of books and on the left side of the upper, shelf, you'll see a portrait of a person. And that is Frank Lloyd Wright. Next slide.

Here is is Archie, painting? This is where he painted in the studio, in front of him, closer to me is the dining room table. And I guess you would probably say I'm sitting in that chair right now. The, you're looking at the back of, on the left hand side of the picture. But Art had his easel always set up at the very north end of the studio, and that was where he painted.

Now, the the dining chairs, the dining table and much of the furniture at Teaters Knoll was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Here you can see how the windows sloped upwards. The curtains I have since removed these curtains that the teachers were very, paranoid about that studio being broken into. And so they had these curtains that they could pull when they were not in residence.

The the light fixtures above the dining room table, I'm guessing, were designed by Pat Teater, but certainly not Frank Lloyd Wright. Next slide.

This is Artie's painting of the inside of the studio. He painted it, numerous times, but this gives a little sense of how it was arranged. And much of this furniture was there when I got there. The large sofa in the front right and the sofa back against the the window, the green sofa and the large globe was not here.

That had been taken away. I mean, you can also see the, the brightly colored Ottomans, they're hexagonal Ottomans that were, in the studio are still in the studio. Next slide.

But I will skip this because this again, is, my my picture of Lester's that Lester talked about the dugout. That was about a mile upstream of Peters Knoll, but still looks like this next slide. This is what is called the Bootlegger Shack. And this was where Archie Archie bought this from, from, pair of bootleggers who had used it as a still during, prohibition years.

And they built a using using the the native rock and and use the spring water for, for, for distilling their alcohol. And it's kind of an interesting thing, but he bought it from them and fixed it up and made it into a house. And you see a couple of things here. You see the red rocks. That on the top of the, chimney are sort of his, his sort of puckish sense of humor and the, the the, curved ridge line of the main studio room.

The main room of the house is also, his work. But this this building still exists near the mouth of the Millet Canyon. Next slide. Here is a wonderful picture that shows, the man on the left. And the picture is, is Robert Pond. Who was this apprentice that Frank Lloyd Wright sent to supervise the construction of the studio?

The man in the middle is Kent Hale. Who is the mason who laying the first, stone? The studio. And the man on the right is is Archie. Of course. Kent Hale is probably the second most important artist, in terms of the construction of Peter's Knoll to the to its designer. His rock work is some of the finest rock work done in any Frank Lloyd Wright house.

The specifications called for it to follow the the pattern of the rock at Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, the famous Kaufmann house that sits over the waterfall. And it has a horizontally laid rock that makes it look as though it naturally grows out of it. So this rock is Oakley stone, and it came from the town of Oakley, where Kent, grew up.

And he essentially opened the quarry to, to do to build Peter's Knoll. And it has just some of the finest rock work as well as some of the finest Oakley stone as as well in the in the Rock. And Kent came back to work for me on two separate occasions. So he worked here in 1953, in 1983, and then again in 1998 when he was in his late 70s.

He was a remarkable friend and I was very fortunate to know him. Next slide. Here are Art and Pat, sitting on the window as the window frames have just gone up. And I show this because they were very much hands on when they when they were building the studio, they may have had their difficulties. And so you in particular was a difficult client for Wright to have to deal with.

And he eventually washed his hands of the project. And it is truly remarkable. It got finished as closely to his design as it did without any supervision from, from apprentices or with Wright's participation. Next slide. Here is pat up on the roof, varnishing some of the fascia boards that are there in the background on the right hand side of the picture.

And that just gives you an example of how they really did participate in the construction. Next slide. And I like this picture because this is some, an unknown, unnamed or unknown. I don't know who this man is, but he's holding a Teater painting, and that is probably how he was paid for his work. Whenever the teachers could could manage it, they tried to.

They tried to pay laborers working on the job, not in cash, but through Teater, paintings. Next slide. This is kind of a fun story. I mentioned how what a great joy it has been to meet people like Lester and another friend who I have met earlier was Monty, later from Saint Anthony, who was the friend of the Teaters through the 1960s and 70s and a close friend.

And, they met often in Jackson, but also the leaders came to, to Noel and met with them as well. But one day Monty got a call from Archie and he and he said, asked asked him if he and Bev could come over to Twin Falls and meet him, that he had something he wanted to show them.

And Monie always like to see Archie and Pat, so we agreed and met at one of those motels along Blue Lakes. You know, below Lakes Boulevard. And when they got there, there was this bright orange Porsche, 911 under the park co-chair. And Monty kind of took a look at it and noted it and then walked inside the the lobby.

And there was Archie, and I can't remember exactly what part of his outfit was the same color, but he was also wearing orange. And he was Archie was just just beyond himself with excitement and, and and anyway, he said, come on out here, my money, I have to show you something. And they got in the car and, Archie sat in the driver's seat and Monty was in the passenger seat, and Archie reaches up and pats the the, dashboard of the Porsche.

And he says one painting, one painting. And what he meant was he he paid for the Porsche, won the sale of one painting. And that was when Archie knew he had really made it as an artist. Next. But. This is how it all looked when I first got here. And the carport is on the on the right and the front door is the left, center and you see that TV antenna thing on the left hand side of the picture that is supporting a 15ft cantilever.

And that was not part of Wright's design, but then Wright didn't there's didn't, include a way to support that roof properly. And so that was one of the things that I had to deal with when I got here. The clear storey, roof, you can see as well. Next slide. This is the view that I first of all, as I looked over the road, you see, you see the diagonal knee brace that supports the cantilever of what we call the prow.

And the prow is a 35ft cantilever. And again, Wright hadn't specified as to how that was to be supported. And that and that they ended up putting that knee brace there, which really bothered my eye when I first saw it. You can see the blackout curtains, in the studio, but the very first thing I did after I bought it was to take that awful the barbed wire down from the from the, fence there that that was, that really bothered me.

And that was the first thing that got changed. Next slide. This was what it looked like probably in the summer of 1982, shortly after I had purchased it. And, and we turned the whole studio into a woodshop and, and put those fluorescent lights hanging from the ceiling and the and the various saws and the equipment. What we were doing here is replacing all of the 105 pieces of glass in the studio with thermal paint.

It was all single pane glass, and it had condensed on the inside and, and, stained all the, all of the wood. And, and that was something that really bothered me. So we replaced it with thermal paint. And it was a project that took, at least six months to do. And, and, really didn't change the general view of the studio that much.

Other. Sure made it look beautiful. Next slide.

The these are the two floor plans that I drove, for my first book, that I wrote about Teaters Knoll and the upper floor plan is the is Wright's original design. And that's the way it looked as I got it when I got to the studio. It is basically a one room, one room studio. The bedroom is actually just a partitioned off area of the of the main studio.

The fireplace is at the heart of the house, which is very typical of a Frank Lloyd Wright house. But what bothered me tremendously was the the workspace, which is Frank Lloyd Wright's word for kitchen and the bathroom are two rectangular spaces that are stuck in the middle of this beautiful geometry that are created by this these equilateral parallelograms.

Right, typically laid out a floor plan using a grid like this. It's somewhat like, staff and music. And the the notes of the music are comparable to the to the pillars and the walls or whatever. It's a very musical sort of architecture. So on the lower plan, you can see that I have moved the kitchen back into that workshop that was pretty much abandoned when I got there and, and, and then expanded the bathroom.

And that was the second major facet of, of the project. And, and the in the lower right hand corner is where the bunk house is, which I, I believe I have a picture of later that I designed and built that area. Next slide. This is what teachers know looks like today. From down near snake River pottery. Looking up at the studio, you can see the cliff below it, and you also can see the prow projecting out and the wood that is kind of illuminated.

There is the cladding that we did to, to cover up that diagonal knee brace which is still there, but you just can't see it. Next slide. And here it is from directly across the river. You can see what a beautiful piece of organic architecture this is. Organic meaning it grows out of the site and, and feels like a part of the site, which is very much the way it was a very important part of Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture.

Next slide. And this is the view from underneath the prow. There you could get a much better sense of how we basically extended the lines of the window sills to through that rock mass, to become this stepped detail that supports that cantilever. Next slide.

And this is the the view looking towards the front door. In 1998, my, my late wife Lynne, and I, enclosed the carport and you can see the carport is the close right close in this view. And the rock walls there are where the the car would have driven in and you literally would have had to have a, Porsche or a car.

The teachers originally had a Karmann Ghia in order to get it in that airport. There's no way a pickup truck could fit that could fit in, but it now serves as an office and storage for us. And that wall, that's closest to you is Kent Hale's last wall. He did that in 1998, in his late 70s.

Just just a remarkable story. Next slide. This is the interior now, looking back towards the front door and showing the the large beam that supports the whole roof coming out of out of the, fireplace and leading to the front. This beam was actually put in place by Artie and by Fisher. Together, the two of them using two hay derricks, raised this this beam into place.

And it had been in in the, lumber yard. And Wendell for a few months, the Teaters hadn't paid their bill. And, the lumber man had said that that, he was would rather see that beam get made into matchsticks than have the Teaters get it. And so they they asked their friend Mardis if he would go over and, and, purchase that and bring it to that.

Right. It's 12in wide by 18in, high by 46ft long. And after they got up, put into place, the Teaters paid for us with two bottles of whiskey. Next slide.

This is looking basically in the opposite direction towards the prow, and you can see the, the window seat is as it was the way Wright designed it. And the those chairs in the picture are called origami chairs. And they were designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, but never, put in the, in the studio. But the drawings were there.

So we built, three of them and the sculptures on the right hand side of the picture and those, those lanterns, are the work of my late wife, Lynn Fawcett Whiting. She was a sculptor, and we we were married in the house, and she lived there for 20 years before passing away about five years ago in the studio.

And she was a very gifted, person and, very integral part of the saving of Teaters. No. Next slide. This is the view of the river. And this is from the bunk house deck. And it gives you a sense of of, of the connection with the river and how close it is. This it, of course, is called Frank Lloyd Wright Rapid.

And it's part of the Hagerman Reach of the snake, which is commercially rafted. And we frequently hear screams of people coming through the rapids, like that through there. The what doesn't show unless you're there or doesn't hear is is the sound. The sound of the river is very loud and it permeates the whole studio, the whole property.

Next slide. This is one of my favorite pictures of Archie and Pat Teater. At the studio, gives you a sense of the, great kindness of Archie. I never knew him, but I, I wish I did, especially when you see a picture like this. And that concludes my slides. But I would just like to say one thing quickly is that people, the many, many people want to come see the studio.

And it just isn't possible for, for me to accommodate everybody who wants to come here individually. But what I want to say is that every June, the Hagerman Valley Historical Society has we have a benefit tour. And people come to Hagerman and have have lunch in the park, and then they come out and tour, Teaters and all.

And we're trying to raise money and awareness to build a museum for the for the, Historical Society, which will in part be dedicated to to Archie Teater and I would welcome you to all sign up for that, or hopefully we can do it this coming year. We weren't able to do it last year, but we've we've done it in early June, which celebrates, Frank Lloyd Wright's birthday in general.

So in any case, thank you very much.

Chelsee Boehm: Thank you. Henry, I'm just going to talk really briefly about, my experience, with Archie Theater and his archival collection. I first learned of Archie Teater in February 2019, when my colleague and I at the Idaho State Archives, we're working on an Instagram post. This is a screenshot of the post, and before we dug out these photos, I had never heard of Archie Peter, but I had heard of Frank Lloyd Wright, who I studied in high school, and I was a huge fan, I guess you can say, of his work.

And so when I learned Archie's connection to Frank Lloyd Wright, I wanted to work on this manuscript photo collection. And when I started working on it, the collection was unprocessed. So that means it wasn't organized. It was a lot of papers kind of just dumped or put into boxes in no specific order. So if you were looking for something in the collection, you would have to look through every box because we didn't know where things were.

There were about 25 boxes in the Archie Teater collection at the Idaho State Archives, and I went through every single one, and I put my grubby hands. Not really. They were clean, but I put my hands on every single document in that collection and organized the collection into something that researchers can use, and easily find documents.

And and that took a little over a year. The cool thing about the Archie and Patricia Teater collection is that it has all kinds of documents. There's correspondence, letters, receipts, furniture, catalogs, and here's an example. Patricia, Archie's wife, kept a lot of these little tiny diaries on the left side of the screen. You can see, you know, one sitting in my hand for scale.

And I have big hands, but they're just little diaries. And on the right you can see where I've gone through and made folders for each of those little tiny diaries, so that you can find what you're looking for. This, like I said, there's a lot of cool stuff in the in the Teater collection at the Idaho State Archives, and this is a letter to the teachers from Frank Lloyd Wright signed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

And like I said, being a fan of Frank Lloyd Wright in high school, I saw this letter and I burst into tears. And there were other people in the room, and it was kind of weird, but it was such a cool experience. And as Henry mentioned, getting to know the teachers and the other people in this community has been amazing.

It's it really is a joy. Early this year, I transitioned from the Idaho State Archives to the Idaho State Museum, where I now help care for artifacts. And it just so happens there was a box of terror related artifacts that were waiting to be processed and, you know, put into proper packaging and those kinds of things and be stored.

So on the right hand side is one of the artifacts I got to work with. It's a lay figure or a mannequin of a horse, you know, that an artist would have used, to create an image of a horse. And on the left is a sketch of horses right from the Teater collection. So you can see how Archie was using these artifacts that are at the State Museum and kind of how that materialized in the archival collection at the Idaho State Archives.

And this last one, this is a palette knife. There are many paint brushes of all different sizes, that are part of the Tudor collection at the Idaho State Museum and a bunch of palette knives. And everything is really fun because it's all covered in paint. This particular palette knife, is really cool because as you can see in that image in the bottom and he has carved Teton has carved his name into the palette knife.

So, you know, it's just shows, you know, his connection to those artifacts. As I mentioned, I spent over a year processing that archival collection at the Idaho State Archives. It's available to the public if you want to go in and research. There is a very large finding aid, which kind of tells you what is in the collection at a folder level.

Like I said, there are about 25 boxes. And that's kind of been the culmination of my work. But I'm so thankful, for this opportunity and to get to talk about, art and to listen to Lester and Henry talk about Archie. So thank you both so much. I think we can turn it over to David for questions.

David Pettyjohn: Yes. If you'll kind of stop sharing your screen for a moment. Oh, and they've got some.

Chelsee Boehm: Go ahead. Yes. Sorry. Very quickly. If you have any questions and you want to contact us, there's my my email and there's Lester's phone number and email. As Henry mentioned, he lives he lives in Titusville. So don't show up to his house and ask for a tour. Please be respectful of his space. But.

Yeah, sorry.

David Pettyjohn: No. That's great. Thank you so much. Chelsee, Lester and Henry, greatly appreciated all that wonderful knowledge. We have just a couple questions, and that's, you know, I don't have much time, so I'll go ahead and, ask these. The first one are prints of Archie's paintings available for sale? If so, where?

Lester Taylor: Unfortunately, no. There occasionally are Archie's paintings. Become available on eBay and elsewhere. But, it's not. Unfortunately, it's not very often anymore. But as I mentioned, he was enormously prolific and the place to, to see Archie's paintings. Now, that is, for the most part, is at the Historical Museum Society Museum in, in Hagerman, town.

There's also a large number of his there's a substantial number of his paintings in Jackson Hole, and the public can see them at what is called the drugstore, which is, a restaurant. But, a good number of his paintings are available there. Also, hey, I have a substantial collection of his paintings myself, and I do enjoy showing them to people, but unfortunately, yeah, as far as I know, no prints of these, paintings are available.

David Pettyjohn: Thank you, thank you. And, somebody asked, Will this program be made accessible for a time? Absolutely. This is being recorded, and we will, it'll be available on our website, which is Idaho Humanities council.org. So, time for two more questions. The first one, this is for you, Henry. After nearly 40 years of being president of teachers.

And. No, please tell us some thoughts and feelings that occur now on a daily basis regarding your relationship with the House and its placement in the environment.

Henry Whiting: Well, that's that's a good question. That's a hard one to answer shortly, but I will just say that I have I observe I'll take a step back. Frank Lloyd Wright homeowners will inevitably tell you, and almost every one of them will say this, that they see something new, in their house every day. And it's one of the great things about it.

I agree with, and what I would say is that, is that what what what one sees basically is the relationship with, with the architecture and nature. And in recent years, I well, I've just been observing this, like you say, for 40 years, but interestingly, I find myself, especially in the afternoon, the light inside the studio.

This is a painter's studio, remember? So the light is just fantastic. And in the afternoon, as the late sun starts coming in and it comes through the those windows and it comes through the leaves on the trees and it will the shadows will, will sort of dance on the floor and it's, it's the most remarkable thing I, I so I essentially find myself turning in towards the house instead of looking out at nature and seeing the sunset.

And the other thing I would say I discovered this many years ago, but but what happens late in the day too, is that the sun will reflect off the surface of the snake River, and it will project itself onto the ceiling of the of the studio, and it will be brightly lit. And actually some days, if it's just bright, you can actually see the reflect the water, the surface of the water projected onto the ceiling, and you can actually see it moving.

And what's interesting is because it comes through the, the, the window, prism somewhat like it actually is flowing in the opposite direction on the roof that it is flowing on or on the floor. And these kind of magical, things just come from spending enough time at the studio. I, you know, of course, I didn't see the see that.

Realized that whole projection thing on the ceiling for about 20 years. And it makes you feel kind of like, what were you doing for those first 20 years that you didn't notice it? Because now it's so obvious. But those kind of secrets keep revealing themselves. And it's it's one of the great spaces I've ever been in. And it's, it's one of the lesser known right buildings, but it's one of the great interiors that's just full of diagonal lines.

It's, it's it's for an artist. It's a place for creation. It's not a place. It's not a house that's meant to be repose. Well, it's meant to be somewhat agitating and and to inspire creativity.

David Pettyjohn: Thank you so much, Henry. And our last question is for you, Chelsee. Are there plans to feature in any upcoming exhibits?

Chelsee Boehm: Hopefully. I have been advocating for an exhibit, about Tudor and his wife at the museum for for a while now. So hopefully, fingers crossed.

Lester Taylor: Can can I add something here?

David Pettyjohn: Yeah.

Lester Taylor: There is planned for this coming summer for the Jackson Hole, historical, museum in Jackson for a full summer of, of Teater. Teacher paintings and art teachers. It was originally planned for this past summer, but it obviously had to be postponed. So that is in the works. And there will be an extremely good collection of, teachers paintings.

There.

David Pettyjohn: Thank you so much for that. And Chelsee, Lester and Henry, thank you so much for sharing your knowledge. It was beautiful. I've seen several, comments of people just saying thank you, for opening up teachers and all, you know, to us and for sharing all those wonderful paintings and for Chelsee, for your dedication in preserving his legacy at the Idaho State Archives.

We're going to take a break next week for the Thanksgiving holiday, but please join us on December the 1st when our next connected conversation will be on the history of Wallace. So thank you all so much. Have a wonderful evening and a wonderful Thanksgiving holiday. Thanks, everyone.

Lester Taylor: Thank you. I'll see.

Henry Whiting: Thank you.