Donald E. Crabtree (1912-1980)

A biography by Julia L. Anderson, Donald Crabtree’s niece

Donald E. Crabtree remains a towering figure in the investigation of stone toolmaking by ancient people. Nearly 50 years after his death in 1980, Crabtree’s groundbreaking publication, “An Introduction to Flintworking,” remains a basic text in classrooms and workshops. Citations of his work in archaeological literature number in the thousands.

Mostly self-educated, Crabtree was a singular expert on the technology and science of prehistoric toolmaking, otherwise known as flintknapping. His replication research is pivotal in the study of debitage, the debris left from rock chipping. He brought stone heat treatment processes to the field of archaeology. Generations of researchers use Crabtree analytics to study rock chipping, rock quarry “workshops,” ancient trade networks and prehistoric settlements.

“An Introduction to Flintworking” published in 1972 continues to serve as the “primary dictionary of flintknapping terms,” said Lorann Pendleton, lithic specialist emeritus, and director of the North American Archaeology Lab at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. “Without this publication, the entire field of lithic analysis simply would not exist. RARE is the scholar who can foster an entirely new field of study. Don Crabtree did that and his work is ageless.”

Indeed, in June 1979, Donald Crabtree was recognized for his lifetime of “outstanding contributions to the field of experimental archaeology” with an honorary doctorate from the University of Idaho.

Early years in Idaho

Donald E. Crabtree was born June 8, 1912, in Heyburn, Idaho, a windy, sagebrush town, population about 230, near the Snake River and the Oregon Trail. The second of three children born to the Rev. Ellis and Mabel Crabtree, young Don moved several times with his parents in those early days as they served Methodist congregations in South Idaho.

In October 1914, the Crabtrees took a new church assignment in Salmon, Idaho, a rough gold rush town then transitioning to a ranching community. Don was not yet 3 years old. In March 1915, his mother gave birth to his younger sister. With two young children, a new baby and church duties, Don’s parents had their hands full. Their 3- and 4-year-old son, Don, roamed free, occasionally running errands for a neighbor lady who rewarded him with arrowheads from her husband’s collection. Several families of Shoshone and Bannock people -- reluctant to leave their ancestral Lemhi Valley for a reservation at Fort Hall -- were living in Salmon. More than once, Don visited his Indigenous friends and later told a colleague that he had asked them how they made arrowheads. “Arrowheads, they told me, were made by coyotes,” he said.

A home in Twin Falls

After relocating seven times in 10 years with the church, the Crabtrees left full-time ministry in 1917 to settle in Twin Falls, Idaho. Ellis, a slight man with a Boston seminary degree, had grown up poor on a hand-to-mouth farm in rural southwest Virginia. Ambitious as a youth, Ellis raised pigs to earn money for school. In Twin Falls, he went back to basics by starting a truck farm on ten acres near the Snake River Canyon while continuing to fill-in as a church pastor around the fast-growing agrarian region. In the early 1920s, the Crabtrees were growing and selling vegetables, raising chickens, and selling eggs using classified ads in the Twin Falls Times-News. “Kraut, celery, dill pickles, eggs. – E.E. Crabtree.”

For 7-year-old Don, the canyon became a magical place to hunt arrowheads and fossils, noted Yuumi Danner in her 2017 Crabtree biography, “Reflections in Stone: A life Story of Don E. Crabtree.” By age 10, Don had a growing artifact collection and had begun trying to make arrowheads,” Danner wrote, “often bloodying his hands and ruining his clothes.”

The obsession worried his parents who tried bribing him to stop with offers of money and a bicycle. Spanking didn’t work. Besides, said his younger sister, Helen Rose, Don was the family’s golden boy and considered gifted. Given his driving curiosity, his obsessive focus on stone tools, and a life-long ability to learn and self-teach, university professors and researchers, as well as friends and family agreed that Don Crabtree was gifted, a one-of-a-kind stone toolmaking genius.

With access to the University of Idaho Crabtree Lithic Collection including Crabtree’s letters, another biographer, Harvey L. Hughett in 2023 wrote that young Crabtree “tried many approaches to holding and applying force (to make stone tools) but with little success and much failure. After interviewing many local Native Americans, he was disappointed that he was unable to learn anything of how these fascinating artifacts were made,” Hughett said. “Flintknapping was essentially a lost art even at that time.”

Twin Falls Pickle Co.

By 1924, the Crabtree truck farm had evolved into the Twin Falls Pickle Co. owned and operated by E.E. Crabtree, selling “Crabtree Famous Dill Pickles” throughout South Idaho. Meanwhile, 12-year-old Don Crabtree, was experimenting with heat and rock using his mother’s woodburning kitchen stove, studying debris piles left from Paleo-Indian toolmaking sites and broadening his interests to fossils, paleontology, and archaeology.

As the Great Depression began, Don graduated from Twin Falls High School in 1931. College was out of reach at least for a while. Saving money, Don lived at home, worked for the Idaho Power Co. and for his father in the pickle business. His parents had sold the property on the Snake River Canyon and bought a new location with more acreage and a big house on the west side of town. Mabel began managing it as Crabtree’s Tourist Home (and boarding house) while Ellis expanded the farm and pickle business.

Despite the Depression, the Crabtrees were doing well enough to help their son enroll at Long Beach Junior College near Los Angeles in 1933 to study geology and paleontology. According to a Twin Falls Times-News story, Don, age 21, was eligible through the school for a position on a Mediterranean archaeological expedition. “Crabtree,” the article said, “had turned “his hobby during his youth into a deep interest in minerology, paleontology and archaeology and has made a study of the subject and gained more than local fame.”

The paper reported that Crabtree had been “called upon to supply the New York Bronx Zoo with a diminutive dinosaur-type lizard, which walks on its hind legs,” and that his “voracious appetite” for remote spots was partially satisfied by his wanderings throughout…the Salmon River Country. “He has enthusiastically put his scientific knowledge to practical use,” said the paper, “having met and talked to the curator of the Field Museum in Chicago where he filled their order for a prehistoric fossil of a rare three-toed horse, which he procured for them in the Owyhee desert.”

As a college student, Don worked part-time as a coatroom checker and studied archaeology. But as a hands-on learner, he became impatient with books and may also have run out of money. By fall 1934, he had left college and was working as a “preparator” in the vertebrate paleontology lab at the University of California, Berkeley. There, according to the Danner biography, he conducted flint-knapping demonstrations for scholars, students and, occasionally, museum visitors.

Years earlier, UC anthropologist A.L. Kroeber had worked extensively with Ishi, a California Native American who in the early 1900s was considered the last indigenous person who could make arrowheads. Ishi died of tuberculosis in 1916. Kroeber observed Don’s self-taught toolmaking techniques eighteen years later in 1934 and told him that “his holding and manufacturing methods were duplicate to those of Ishi.”

Back in Twin Falls later that year, the newspaper reported that Don had collaborated with a friend for a downtown window display featuring items from their collections including a mammoth tooth and “huge” (mammoth) socket joint, a mortar and pestle used by Paleo-Indians, along with a “significant display of arrowheads, most of them found in a cave in the Minidoka desert.” At the time, such collecting was legal.

In commenting on the exhibit, Don revealed his deep understanding of prehistoric stone toolmaking techniques when he explained that “each tribe (in the region) had its own style of arrowhead, and that each tribe member varied his heads slightly so that they could be identified (individually) after a hunt.”

Career interruptions

From the start, Don Crabtree’s career was uneven. Throughout the 1930s, his father had hoped that he would join him in the pickle business. But Don was engaged with the University of California researchers as he gained more knowledge and confidence with his stone tool skills. That work came to a halt in 1939 when at age 27 he was diagnosed with cancer, resigned his position at Berkley, and came home. His mother, Mabel, who had grown up on a Kansas “poor farm” run by her parents and trained as a church deaconess, nursed him through months of harsh radiation treatment and surgery for what was likely testicular cancer. Eighteen months later, declared cancer free, Don spent hours flintknapping to recover his strength and to work on technique. In early 1941, he was invited to a meeting of the American Association of Museums in Columbus, Ohio to share his stone tool research. He consulted for two months at the Ohio State Historical Society Lithic Lab. He worked at the University of Pennsylvania as a lithics advisor, then visited the Smithsonian Institute to consult on the Lindemeier collection of Folsom points discovered in Colorado in 1924. The beautiful Folsom stone tool fluting technique was used by Paleo-Indians to make points, scrapers, knives, and other tools 11,000 years ago. Investigating Folsom manufacture became a years-long obsession for Don Crabtree.

His exploration of ancient toolmaking meant compiling “copious notes of platform preparation, documenting the amount of force, angle of seating the tool, angle of applied force, termination of flakes, etc., until he was able to interpret many techniques of both the Old and the New Worlds,” wrote Hughett for his University of Idaho-based profile. “His goal was to manufacture an exact duplicate of an ancient tool, not a close imitation. He never stopped learning.”

World War II interrupted his work, again. As the war started, Don Crabtree went to work in California for Bethlehem Steel Co.’s shipbuilding operations as a coordinating engineer. During the war in 1943, he met and married Evelyn J. Meadows. Both 31, each with prior health issues, Don, and Evelyn (who had lost a lung to TB) formed a deep bond. She was his confidant, his secretary-editor and traveling companion. Before her death in 1976 at age 63, she had become his manager-gatekeeper as letters, scientific papers and research conference invitations flooded into their rural Kimberly, Idaho home.

Return to Idaho

After the war, Ellis, then 71, and Mabel Crabtree, 61, retired and moved to a smaller house in Twin Falls where they continued to make pickles in their basement and host Sunday family dinners. The Crabtree Pickle Co. was sold to Don’s older sister, Virginia, and her husband, Lewis Hack. Don and Evelyn took over the Twin Falls “motel” business and property that they later sold. Don then went to work for the local office of the federal ASCS (Agricultural Stablizatioin and Conservation Service) while continuing his research work related to stone tool replication.

In 1958 and again in1959, Don and Evelyn made trips to Mexico to learn more about how ancient Mayans flaked blades from obsidian cores. Diving deeper into translated toolmaking observations written in 1615 by a Franciscan friar, Crabtree devised a chest crutch with an extended attachment and antler point to “punch” fluted razor-thin blades from a core. He successfully used the technique with his Folsom and Clovis point experiments to create nearly perfect fluted points.

In the 1950s, Crabtree began sharing his flintknapping expertise and research with Dr. Earl Swanson, professor of anthropology at Idaho State University in Pocatello. The relationship intensified when in 1962, Crabtree experienced a coronary occlusion while hunting for obsidian volcanic glass specimens in the desert near Arco, Idaho. The “attack” weakened his heart and forced him to retire from the ag job but gave him more time to experiment.

As a lithic technology research associate at the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Crabtree began publishing his work through the ISU journal, “Tebiwa.”

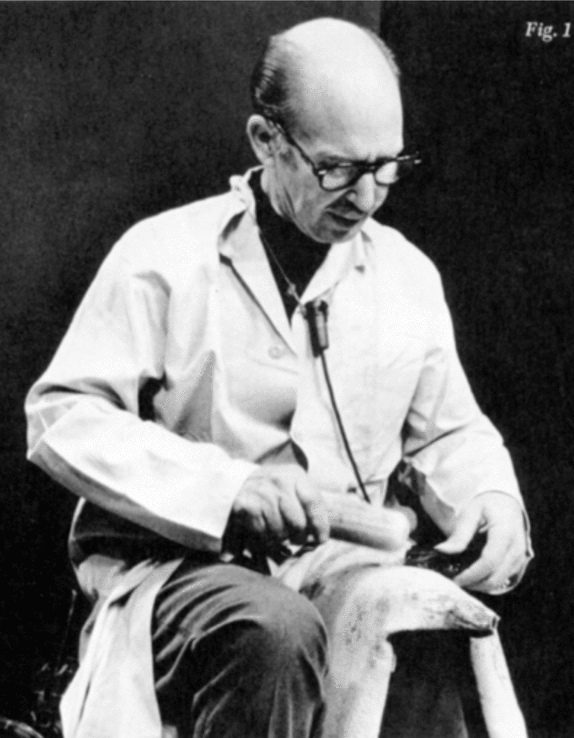

In 1964, supported by National Science Foundation funding, Crabtree attended a Lithic Technology Conference in Les Eyzies, France. There, Dr. Francois Bordes of the Laboratory of Prehistory of the University of Bordeaux, and Dr. Jacques Tixier with the French Institute of Human Paleontology became fascinated with what Crabtree was doing. In 1968, “Blades and Pressure Flaking,” a film (available on YouTube) made in collaboration with Bordes elevated “Mr. Crabtree” to international status. Bordes called him “a world authority on pressure flaking technique.” Tixier and Bordes became friends with the Crabtrees and visited their Idaho home more than once. Others included Dr. Norman Tindale of the University of Adelaide in Australia who was investigating Aboriginal toolmaking.

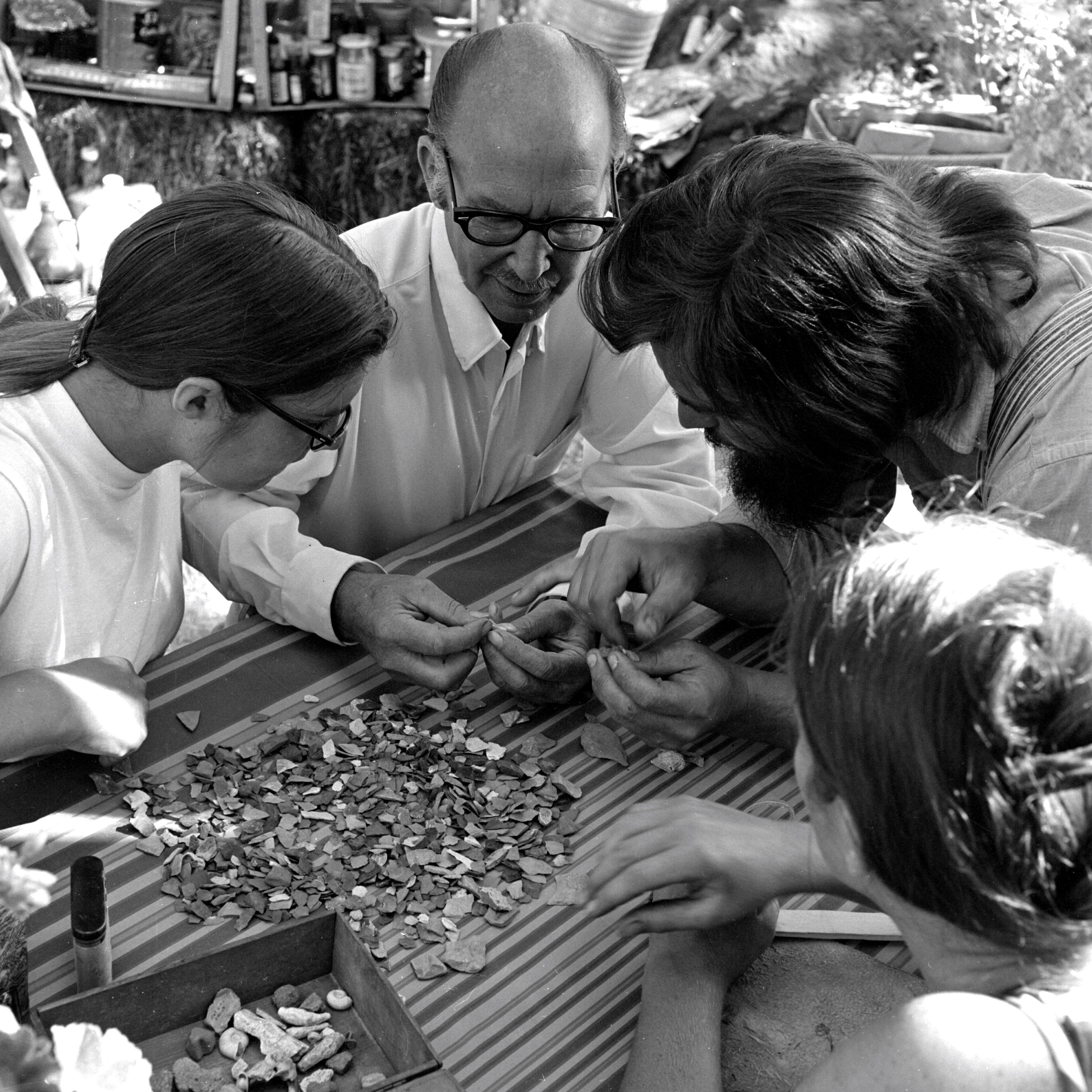

With National Science Foundation funding and the Idaho State affiliation, a cadre of young graduate archaeology students were selected to attend Crabtree Field Schools, held summers near Twin Falls from 1969 through 1975 where Don Crabtree shared his skills and mentored attendees. The field schools ended with Swanson’s sudden death at age 47 in 1975.

Washington State University’s Lithic Technology Lab hosted similar field schools throughout the rest of the decade with Crabtree in attendance. Early on Swanson used NFS funding to produce five films featuring Don Crabtree showcasing his work. The films remain available through the Idaho Museum of Natural History’s YouTube channel with these titles: “The Shadow of Man,” “The Flintworker,” “Ancient Projectile Points,” “The Hunter’s Edge,” and “The Alchemy of Time.”

The Crabtree Phenomenon

In the 2006 fourth edition of his classic textbook, “Archaeology,” co-author, archaeologist and historian Dr. David Hurst Thomas wrote that for 40 years Crabtree tried every way he could think of to make Folsom replicas. “In his (Crabtree’s) published account, he eventually described the 11 different methods he had tried to remove fluting flakes,” Thomas wrote. “Most simply did not work.”

Only when Crabtree devised a chest crutch using the Spanish friar’s description, did he find success. “The resulting artifacts,” Thomas wrote, “were almost identical to prehistoric Folsom points.”

“Crabtree’s pioneering research unleashed an avalanche of experimentation in the fluting problem,” Thomas observed. Many researchers took on the challenge over the next two decades using variations of his techniques to uncover the Folsom secrets from 11,000 years ago.

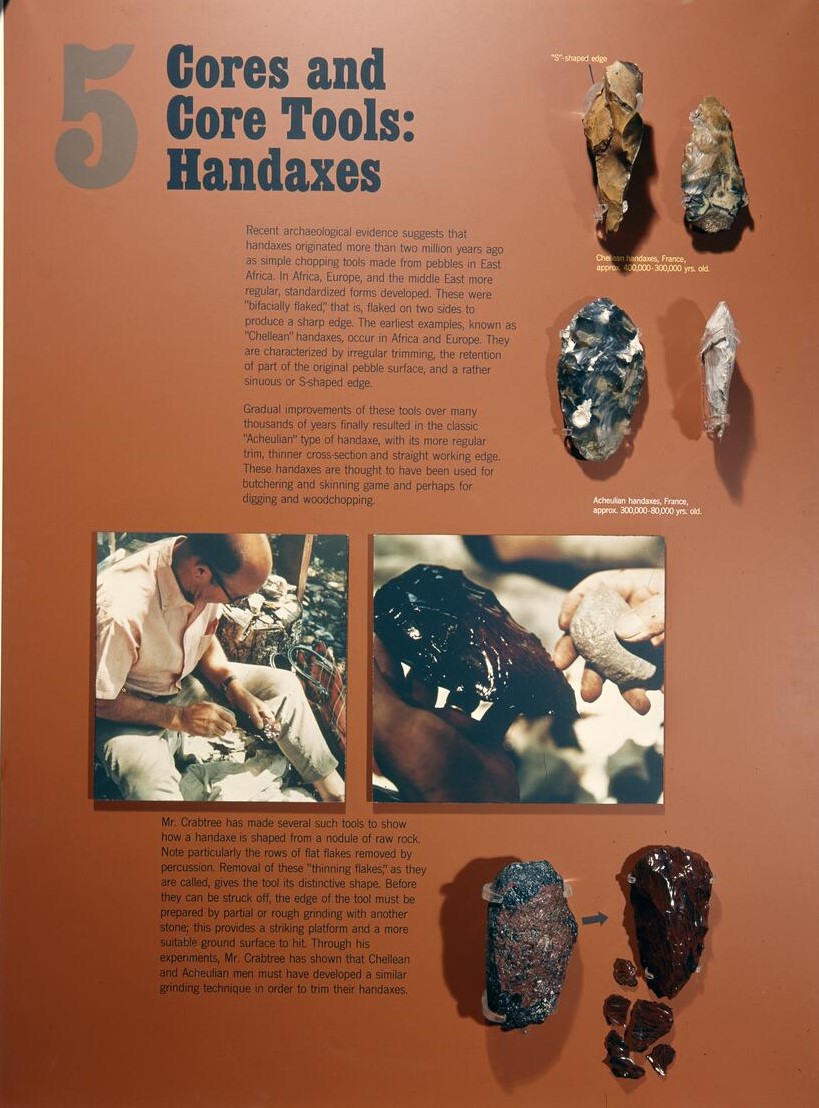

At the height of the “experimental archaeology” explosion, Don Crabtree was featured in a “living” exhibition, titled “Stone Toolmaking: Man’s Oldest Craft Recreated,” at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The exhibition opened Feb. 19, 1970, showcasing Don Crabtree’s flintknapping skills as he replicated stone artifacts from the museum’s collection. Interpretive panels accompanied the exhibition. An introductory panel explained that most stone tool technology had been lost in time. “Scholars must find other ways to reconstruct the technology and behavior of ancient man, and one of the best ways is ‘experimental archaeology,’ an approach which is currently being advanced by the flint-knapping of Mr. Donald Crabtree.”

In 1972, Don Crabtree published his groundbreaking 100-page illustrated “An Introduction to Flintworking” through the Idaho State University Museum. Lorann Pendleton, lithic specialist, and director of the American Museum of Natural History’s archaeology lab has used the work in her mentoring classes for years. “It’s the first publication I assign, as it is still the bible on flintknapping.”

In 1969, Crabtree received a letter from Karen Tobias, editor of Books for Boys and Girls, asking him how his fascination began with stone tools. “When I was seven years old,” Crabtree answered, “I became interested in hunting artifacts in the deserts of Idaho and eventually became intrigued about their manufacture.” Twin Falls, Idaho anthropologist and Crabtree friend, Jim Woods, was among those who learned from Don Crabtree. “Don was a gentle, compassionate gentlemen. He liked to talk to people, learn their stories.,” Woods remembers. “Some people were star struck by him. People with a billion publications would come to his house just to meet him. He was generous with all of them. Lots of people know Crabtree through that experimental learning-by-doing lens,” Woods said.

An Honorary Doctorate

By the end of the 1970s, Don Crabtree was no longer able to do much flintknapping. Heart surgeries, Evelyn’s death from cancer in 1976, his smoking and a lifetime of striking rocks against rocks affected his health. His conversations continued with researchers, and he attended the WSU field schools in Stanley Basin, Idaho.

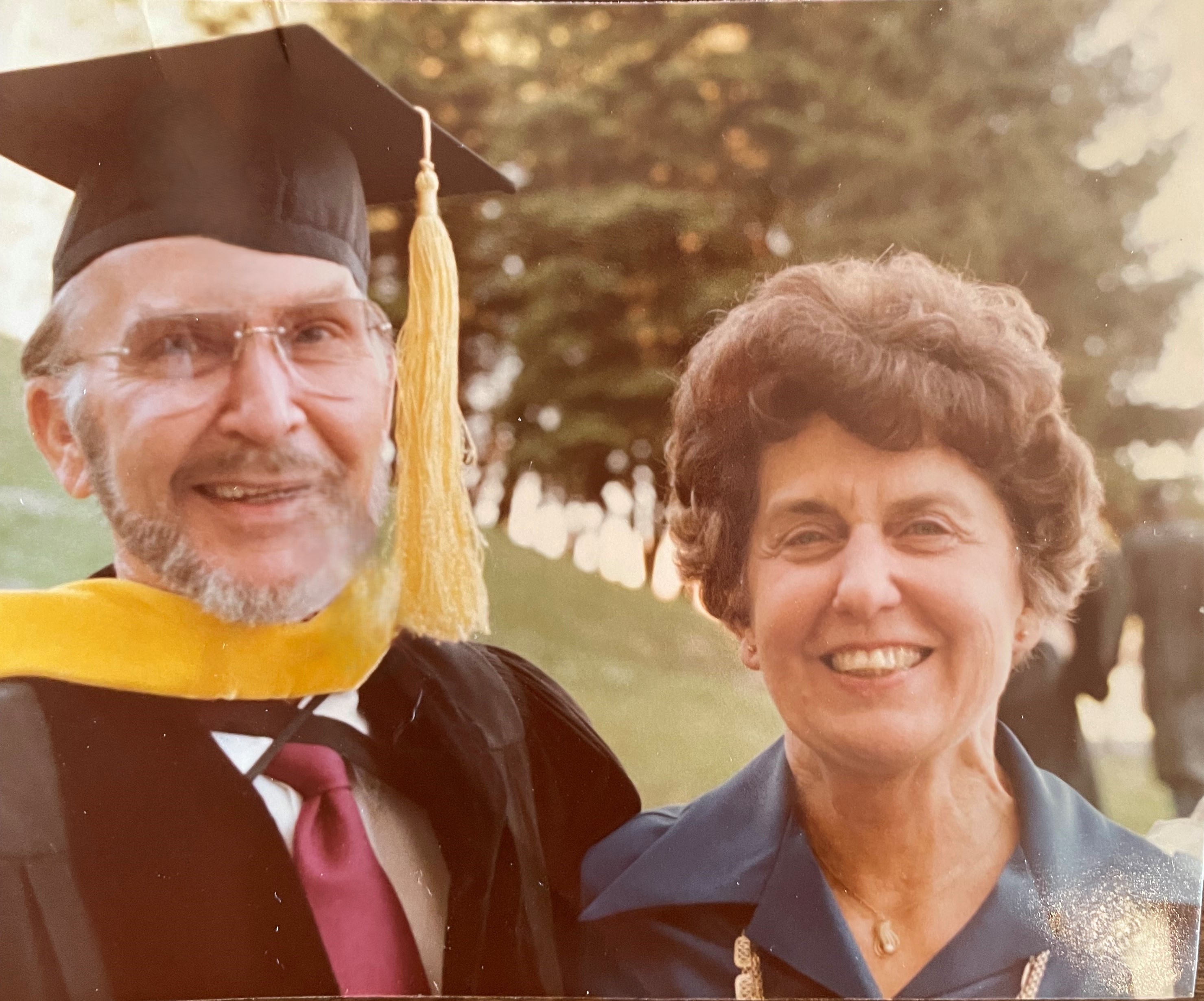

In June 1979, Donald Crabtree received an honorary doctorate from the University of Idaho.

“Don Crabtree deserved every bit of recognition that that came with his honorary degree,” said anthropologist Dr. J. Jeff Flenniken, who was an early Crabtree Field School student and who hosted the WSU field schools into the 1980s. “The real importance of what Don Crabtree did is not in the lithic collection at Idaho but in what Don showed people how to do. He could see things that I didn’t. He could see things in three dimensions. I can’t name anybody who came close to Don Crabtree,” Flenniken said.

Don Crabtree died at age 68 in November 1980. At his death, the Crabtree lithic collection and research papers went to the Alfred W. Bowers Laboratory of Anthropology at the University of Idaho. The collection includes 3,154 stone tool replications made by Crabtree and by others as well as 4,391 archival items -- photographs, slides, research documents, and correspondence.

In 2021, the University of Idaho Library and the Bowers Lab received a $240,206 three-year grant to digitize the Crabtree collection, searchable at the UI Library Donald E. Crabtree Lithic Technology Collection website.

- By Julia L. Anderson (Don Crabtree’s niece), 2025