Perez, Rita

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

Transcript

Rosa Rodríguez: This is Rosa Rodríguezand I will be interviewing Rita Pérezfrom Idaho Falls.

Rita, can you tell me your whole name and where you were born and what year you were born?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Rita Padilla Pérez. I was born 1930.

Here in Idaho Falls.

Rosa Rodríguez: Do you know when your family came to this country?

Rita Padilla Pérez: My father came in 1911.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did what? What, state did he come to?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Texas. But he did not stay there. I believe he went on to San Francisco.

Rosa Rodríguez: And what was the reason that he came to the United States?

Rita Padilla Pérez: A dream of coming to a rich country where people could easily make a lot of money.

Rosa Rodríguez: Why did, why did he move from Texas to, to California.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Where he could find work with, I believe he worked mostly with a railroad. So whoever that work took him, that's where he went.

Rosa Rodríguez: And how long was he in California?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Off and on, I believe. Until 1925.

Rosa Rodríguez: Would he, be in California and stay the whole year, or would he just work, cease and then go back to Mexico?

Rita Padilla Pérez: He went back to Mexico 3 or 4 times. But then he'd come back to wherever there was work.

Rosa Rodríguez: And was it always California?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. He went as far east as, Illinois.

Rosa Rodríguez: Working for the railroad. Working for. And when was the first time there he came to Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: 1919

Rosa Rodríguez: 1919. What was the reason that he came to Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I believe they came contracted by the sugar factory.

Rosa Rodríguez: And did he ever work in the railroad when he was in Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, yes. The Keystone at one time, he had work from Pocatello sent to Alexander near Soda Springs, then to Bancroft in or hum black food. Saint Mary's.

Rosa Rodríguez: When did your mother come to the United States?

Rita Padilla Pérez: 1925 no. 1924 two came right after they were married.

Rosa Rodríguez: And did they come directly to Idaho, or since your father had been here since 19 oh 19, did they come directly to Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. First they stopped in Arizona to visit my father's sister, who lived there. But it was in July and they could not stand the heat. They went to San Francisco, where my father had a brother living and.

Rosa Rodríguez: And then they came to Idaho.

Rita Padilla Pérez: My mother was a country girl. She couldn't take city life. And my father had to work night shift all the time. Her health deteriorated to the point where a doctor told my father he had to get her out of the city, out in the country that she was accustomed to. So they were saving for the trip. When my father was laid off.

Rosa Rodríguez: They were staying for the trip to Idaho. Yes. And and, How did they come to Idaho? By train.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: They came by train. How much did it cost for them to to come over?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I don't know, but, my mother said that my father only had enough money. There was only enough money for one day fare for one person. And my father proposed them putting her on the train and then bombing himself. Meeting her here. She was petrified at the thought of traveling alone, not knowing the language. So when he left to take care of final business, she cut her hair that was down to her knees off and pulled a cap over her ears and put on his clothing, overalls.

When he returned, he was aghast to the point of tears and. She just gave him an alternative. Either she'd accompany him or he could take her back to her parents home.

Rosa Rodríguez: So he he brought her with him. Do they ever tell you how long it took them to to come to Idaho? The length of time it took them from California to Idaho.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, I can't remember my mother ever telling me. But she did say that they they walked to the outskirts of San Francisco, where they boarded a train in the dark. They had no problems until they got to. They were on the train over the Salt Lake City, Utah, when the conductor caught them. And he wasn't about to believe that she was this man's brother, and told my father to tell it to the authorities in Salt Lake.

It's a good thing he had to tend to his work, gave him a chance to get off the train and hide under the bridge until night when everything was no sign of life or danger of getting cut again. And they walked. They walked clear to Ogden, walking at night and hiding. Sleeping during the daytime.

Rosa Rodríguez: Why were they hiding and why were they?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Because they were afraid that if they tried to catch a train again in Salt Lake, the conductor might have warned the authorities and they would be looking for them on the trains.

Rosa Rodríguez: Because she didn't have a ticket or because, she was a woman.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And neither then and neither of them had a ticket.

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh, I see in.

Rita Padilla Pérez: They were they were afraid they would be separated.

Rosa Rodríguez: So they came to she he brought her to Idaho, to Idaho Falls in 19.

Rita Padilla Pérez: 20

Rosa Rodríguez: 25. And he had already been living here since 1919.

Rita Padilla Pérez: He had not been living here all the time.

Rosa Rodríguez: Just just off and on, off.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And on from there was work.

Rosa Rodríguez: There was work with the railroad and the sugar company.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And the potato harvest and.

Rosa Rodríguez: The potato harvest. What did, did your father find, job right away? When when your mom came with him that first time.

Rita Padilla Pérez: When they came here to Idaho, I believe they were. They had been living in town, and he was going out to work on a farm in Ammon. To them beets. So then when.

When it was time for my brother to time for my brother to be born.

He. They had talked to a midwife, but he had to go bring her. He brought her and he was going to go off to work. They had to work when there was a chance and a midwife said, wait a minute, you are staying here? Where I go, my, my father wanted to go back, go to work and do what he could when he could.

You said, you're going to stay here. This this is your first baby. But it won't be your last. Your there's going to come a time when you will have to know what to do. And so my father had to stay. And she told him told him why she did everything she did. And using sterile technique. And he did.

And he did use a good, sterile technique, better than some doctors and nurses that I saw. So it's a good thing she did.

Rosa Rodríguez: And, so, so your your first brother was born. Your older brother was born? Yes. And what year was that?

Rita Padilla Pérez: June 9th, 1926.

Rosa Rodríguez: And was there other Mexican family out there in Idaho Falls?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, because they had told them about this, midwife to contact.

Rosa Rodríguez: The midwife was Hispanic?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. An older, elderly, very Indian woman.

Rosa Rodríguez: I see. So then did you you did. Did your parents use a midwife for all of the children? Where were you born, Rita? Were you born at home also? Yes. And so how many of your brothers and sisters were born at home? How many are you in your family?

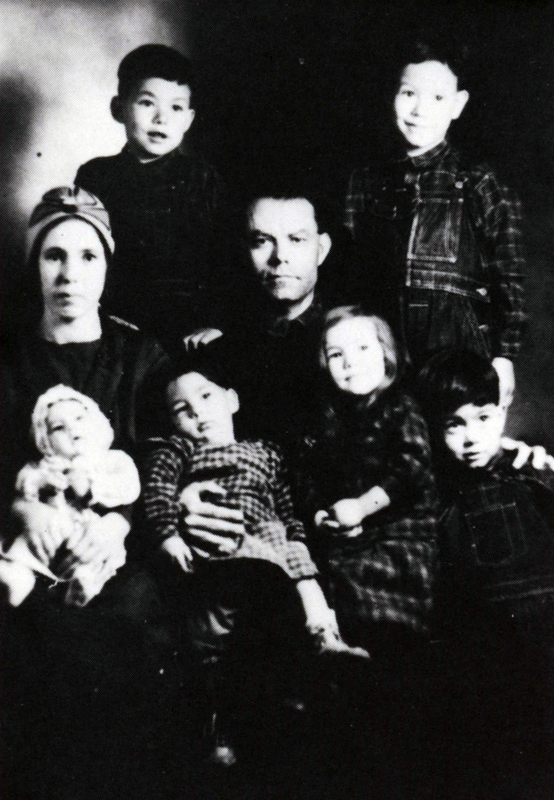

Rita Padilla Pérez: There are. Well, now there's only 15 living. Since one of my sisters died recently. Just, November 1st, 1989. So there's, three older boys, and I see so many. Sandra that died. Julian. All. Alex. The eight of the first night of the second. Alex the first. Alex the second. 12 were born at home.

Rosa Rodríguez: 12 were born at home. And and, when did your mom start? Having her babies in a hospital.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Joséph was born in 1944. We were living at, labor camp. Casey out of Pocatello.

Rosa Rodríguez: I see.

Rita Padilla Pérez: You know, all these other woman started telling her all these horror stories about a woman who had died in birth, and she got two cats. I think, to be able to have a baby, naturally.

Rosa Rodríguez: What was the name of that labor camp again?

Rita Padilla Pérez: It wasn't a labor camp. It was just the owner of the store had a little park there and had cabins. We rented a cabin, but then a lot of other people came and pitched their tents in a little park. He had to. And in the center.

Rosa Rodríguez: There are a lot of Hispanic people there. Yes. And what year? What year was that? That Joséph was.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Born 1944.

Rosa Rodríguez: 1944. So how many of you live in Idaho Falls? Still? Most of you live in Idaho.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Most of us one sister lives in Boise. And the one that I lived in Oregon and dose of lives in Pocatello.

Rosa Rodríguez: So the house where you were born, Rita. Where was that house?

Rita Padilla Pérez: On Fremont Avenue, where the home is now.

Rosa Rodríguez: And you still have your home there? Does someone still live in that?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. My two brothers.

Rosa Rodríguez: Your two older brothers live there.

Rita Padilla Pérez: They just recently the city demanded that their old house be demolished.

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh, and they have to.

Rita Padilla Pérez: It has been demolished.

Rosa Rodríguez: It has been. When was that?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Just this.

Rosa Rodríguez: Last year in the fall. So how so? When your father moved here with his wife? With your mom? In 1924, we moved here to Idaho and moved here to Idaho Falls. Did he come to live in that house? Was that their first home?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, no, they they had been renting somewhere in the Riverside.

Rosa Rodríguez: By the river.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No more between the river and the tracks. Where for the senior living central.

Rosa Rodríguez: I see.

Rita Padilla Pérez: How about J... J or K Street?

Rosa Rodríguez: And how long did they live in a rented home?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Until 28. They bought, well, they had bought a lot on K or J Street and started building, but he did not have money to complete the building. So the fire department made him cut up the frame and told him to move it out because he was a fire hazard. A man that he used to work with told him that there were lots up near the river that he could, buy and didn't even have to make a down payment on or what, settle for $5 down and my father would have to pay the property taxes.

So they cut up the frame.

Rosa Rodríguez: $5 down for a down payment and a lot.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Great, sure. But they didn't even make a dollar a day. Then.

Rosa Rodríguez: That's true.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And there. So they had to cut up the frame that he had put up for this house on K or J Street and move it to that place over there. It was just like a sand dunes with a lot of piles of garbage here and there.

Rosa Rodríguez: And he built and he's the one that built the house ladder.

Rita Padilla Pérez: So he, they, they put the frame together the best they could. There on that place.

Rosa Rodríguez: Who is.

Rita Padilla Pérez: They? My parents. And this, coworker of my fathers that had helped about the slats.

Rosa Rodríguez: A friend of his. Yes. And he helped him build the home. And you live and you lived with your brothers and sisters and your mom and up there for how long? How when was the one with the house? Demolished.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Thank you.

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh, last year with you. So your older brothers still lived there till then?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, we built, a bigger house in 19 and started building it in 1965. No, 1960.

Rosa Rodríguez: You just added on, or you built.

Rita Padilla Pérez: An entirely totally new house with a basement in Greek. The older house was behind the shop that my brother built up later have.

Rosa Rodríguez: And you have pictures of your house? Of your first house? Yes. That your dad.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Built? Yes. My sister and brother took pictures before it was totally demolished.

Rosa Rodríguez: How many other families Hispanic families lived in Idaho Falls? When? When you were born? Or when you. As long as you can remember. As far back as you can remember.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Just two, three.

Rosa Rodríguez: 2 or 3 families.

Rita Padilla Pérez: That used to live here. There used to be a lot of Hispanic families that used to come from southern Idaho, Texas, California, New Mexico, Colorado. But they did not stay. They would just come to pick green peas and stay for the potato harvest. You know, some of them wouldn't even wait until the potato harvest was over, when, if you got too cold for them to eat at home.

Rosa Rodríguez: And where did your your father work? Did he work all year round?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. Remember 1936? He came over joyed because a neighbor had given him a dollar for working all day, cleaning up big pans.

Rosa Rodríguez: I see, so he had to work at at odd jobs. What was what was the main job that he did? He did.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Some work. Started with thinning beats, hoeing beets. Then we would go to Driggs and pick green peas and come back about mid September and potatoes. And after the potato harvest was done, if there were any sugar beets to harvest, then we'd look at that.

Rosa Rodríguez: And when you went to drinks, how old were you.

Rita Padilla Pérez: The first time? I can remember I was four going on five.

Rosa Rodríguez: And how many brothers and sisters did you already have?

Rita Padilla Pérez: The three older ones than I do. Younger sister.

Rosa Rodríguez: So there was seven.

A handful of, children. Did when you when you would go to drinks, you would stay there and drinks and work.

Rita Padilla Pérez: I always stayed there for probably about six weeks.

Rosa Rodríguez: And where did you live?

Rita Padilla Pérez: They had, a place, a clearing in the forest where they were. We were allowed to either pitch tents or build shelters out of bark.

Rosa Rodríguez: How many other families worked there?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, quite a few. There were 3 or 4 families that we knew quite well, but there were probably about eight other families. Hispanics.

Rosa Rodríguez: So was that a self-made? Labor camp type of work?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, I believe that,

Contractor made arrangements to a lot of people. To camp.

Rosa Rodríguez: To camp up.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Camp out there.

Rosa Rodríguez: What was the name of your the contractor, James White. And he was the one that would find those jobs. For instance, that job picking peas.

Rita Padilla Pérez: He'd, contract with, farmers, and then he would provide, all the labor.

Rosa Rodríguez: How did you how did he communicate with your father if your father.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, my father spoke, broken, but very understandable. English.

Rosa Rodríguez: And so you lived there for six weeks.

Rita Padilla Pérez: How about.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you did you ever work there, Rita? Did you ever help your your mom and dad?

Rita Padilla Pérez: The first time that I worked out in the field, I was about eight years old.

Rosa Rodríguez: And what did you do before you worked out in the field?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Babysitter.

Rosa Rodríguez: You took care of your little brother and sisters. And your two. You three older brothers worked?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: And your mom and dad also? Yes. And then you would stay in the in the tent?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. No, they they would take us in the car or truck and park it at the end of the field where my mother could come at intervals to check on the baby in nursing.

Rosa Rodríguez: How old was the baby when you when you, took care of her?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, the first time I was left in charge here, my younger sister, she was about six weeks old.

Rosa Rodríguez: And how old were you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Not quite five.

Rosa Rodríguez: And so. How long did your. What was a normal working day for your mom and dad? How long did they work at? You have to take care of your.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Farm from sunrise to sunset. Kidding. This could be from 4:00 in the morning to 9:00 at night picking green peas because it was under the contractor. And he said that he or she was from 6 to 6, probably.

Rosa Rodríguez: And so then you went you went there. How many years to try to pick up?

Rita Padilla Pérez: As far back as I can remember until 1945, at least.

Rosa Rodríguez: Tell me a little bit about how how you how your parents picked the peas. Also, I would it would be nice to know how much the contractor got paid for, as part of his wage.

Rita Padilla Pérez: I have no idea what the contractor got paid. I think that we might have been paid about $0.03 a pound.

Rosa Rodríguez: And was it in barrels or what? How did you. How did your parents.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Know they had, wooden baskets that were some kind of cylinder shaped, starting with about a 12in at the bottom and coming up to 24 or more inches at the top across.

Rosa Rodríguez: So kind of maybe if you could describe to me your first memories of Idaho.

Rita Padilla Pérez: My first memories of Idaho was home. My father always planted a big garden in the nine lots we had. I remember walking out the door and, squash were in bloom. I thought it was beautiful and.

Dead. I had no notion as to state.

Rosa Rodríguez: You didn't know there were other.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. It was just a very small world. Just,

Rosa Rodríguez: Idaho Falls.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And not even Idaho Falls. It was just one of my first recollections. Was just home. The lot, the fence around it. And we were not to be, inside that fence.

Rosa Rodríguez: So then did you have neighbors?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. But, they were not, friendly, to say the least.

Rosa Rodríguez: Why were they not friendly? What was it that they did that?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, discrimination. We had, one neighbor that during the depression, my parents raised chickens and he wanted my father to give me my hand. And my father said, no, you're getting help. We're not getting any.

Rosa Rodríguez: What? What do you mean by the neighbor was getting help? What does that mean? Welfare.

Rita Padilla Pérez: But we. Because my parents were Mexicans, we were Mexicans. I got no help from Mexicans. It was told.

Rosa Rodríguez: By, say, during the.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Depression, during the depression. And so here this neighbor who was getting welfare wanted my father to give him my chicken. And my father said, why should I give you my give you a chicken while you're getting welfare? And this is all we have? So he. Rondo chicken coop. They found a tire. The fire had been started on a tire and there were rags with gas on them.

And called the fire. The neighbor across the street called the fire department and helped my parents carry buckets of water to throw on the house to keep the fire from burning the house that we lived in and the fire department came, but they wouldn't do anything. They just sit there. They said, think.

Rosa Rodríguez: They wouldn't stop the fire?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. So my parents and the neighbor carried buckets of water to.

Rosa Rodríguez: So how were you treated? Like, for example, you would go to the grocery store.

Rita Padilla Pérez: I don't know, because we were never taken in the grocery store when we were children. My father went and got the groceries. That was it.

Rosa Rodríguez: Your mom stayed home?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: And your father, never talked about the way he was treated?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. Father never said anything about how he was created in the grocery store.

Rosa Rodríguez: Or in any other place. Would he also go? How? What kind of clothes did your mom so for you in your clothes, or did you buy your clothes? No.

Rita Padilla Pérez: My mother sewed most of her clothes and. Hers?

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, at the time, would you say that maybe there would be maybe one grocery store and describe to me I'd have off at that time?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I will. I can remember it. Is that on the way to work? There was a blacksmith shop where trading center is now on Memorial Drive. There was, the park. What is now the parking lot was more like a dump. A lot of piles of garbage and hitching posts. I believe quite I know it was already there, across the alley from taking center.

Rosa Rodríguez: But, like on a Sunday, a typical Sunday. Did you have to work? Did your parents work on a Sunday?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. When they were working for an individual farmer, they set their own hours and they worked from sunrise to sunset when there was work to be had.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, especially in this area, Rita, the people, the religion that's dominant here, they don't believe in, working on Sundays. Why is it that you work on Sundays?

Rita Padilla Pérez: The farmers that we work for most. Well, I don't know. I know one farmer raised a kid. My father, he'd be a good Mormon because he had so many children. But that was said he was free to work or not. I mean, he was free to work when there was work to be had. They never told him he could take time off.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you go, did you go to church? To a church service? Oh, no.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, there was no church. My parents, we prayed at home, but I didn't know where the church was until I was 22.

Rosa Rodríguez: Until you were 22. And where was the church in.

Rita Padilla Pérez: ...

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh so they had a church. A church built. What religion? With that being Catholic. And they, they had built a when did they built that church?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I believe it was built in 1944.

Rosa Rodríguez: 1944

Rita Padilla Pérez: That's the new one. There used to be a church keep a corner from where the church is now for the school is playgrounds. Now.

Rosa Rodríguez: Tell me your if you could describe to me your, first days of school. What were they like? What did you start school in kindergarten? Was there kindergarten or did you start first grade?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Started first grade in the harbor, I believe.

Rosa Rodríguez: What is that?

Rita Padilla Pérez: The harbor. It's place in Orange County, a little town.

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh. In California? Yes. Oh, I see okay. So then your your family would go to California to work?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. And to get out of the cold.

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh, so you didn't you didn't stay here all year long.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, my aunt and uncle came in 1934 and kind of into my father to go to California, where there was work to be done. As it turned out, the only work my father could get was picking citrus fruits, and he turned out to be allergic. He'd get out all over it any time he got under the citrus fruit trees.

Rosa Rodríguez: So he had to fight another job.

Rita Padilla Pérez: So some coworkers told him there was work in Imperial Valley picking green peas. So after that, we started going to Imperial Valley and on to Bakersfield, where there was work picking green face again.

Rosa Rodríguez: And when would you come back to Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: When the weather got, so hot my father couldn't stand it anymore. One time about mid-March, he went and picked us up at school and he took a truck, already loaded, head for home.

Rosa Rodríguez: It was always exciting. Must have been always.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Like we were like gypsies and always looking forward to see if we show our friends. We would see again.

Rosa Rodríguez: In the different towns that you would. Well, now, tell me, how was it in the first grade in, in, in that school in California?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Not bad. Well, mostly we were segregated in there. We were just Mexicans. No Anglos that I would call off and they had festivities and.

Rosa Rodríguez: Why were you segregated?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I think it was the norm at that time.

Rosa Rodríguez: So then what, you would go to a different school than the white students?

Rita Padilla Pérez: All I remember that there were no Anglos there, just Mexicans.

Rosa Rodríguez: And the school that you had that you were.

Rita Padilla Pérez: In, that I think we went to,

Rosa Rodríguez: When your father first registered you in school in California. Did he go to the right school he should have gone to, or did he go to?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I think we were just sent with our cousins. And.

Rosa Rodríguez: So were there a lot of, Hispanic students there?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, yes. There were. Only Hispanics.

Rosa Rodríguez: And no other.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Race. No other race. There were no no blacks there. Okay.

Rosa Rodríguez: Tell me, so you were in school in California in the spring or.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Mostly in winter. Just winter and maybe part of spring until work started.

Rosa Rodríguez: So tell me your first memories of going to school in Idaho. How old were you? In what grade was that? But that would be still the first grade.

Rita Padilla Pérez: It was still. It was still first grade.

But I think I had learned enough English, probably, that I was not aware. And even though you don't understand the language, you get the message. But when we were in Idaho Falls and we were the only Hispanics in at Riverside School, then you was either. You learn to swim or drown. So we learned English because we were the only ones that spoke Spanish.

We had to learn to speak English.

Rosa Rodríguez: Were you accepted? Well in the school?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes we were.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you have a lot of friends, Rita?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I can't say that. A lot of friends. But, we got along fine.

Rosa Rodríguez: Were the teachers.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Good teachers? Most.

Rosa Rodríguez: Most of.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Them. Most of them were very kind and understanding.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you, go to school there then? In the spring?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. We started school after the potato harvest, and the beet harvest was all done and there was no more work to be had. We started school sometimes we didn't start until mid November.

Rosa Rodríguez: But would that be in Idaho or in California?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Either place, wherever. If, if we went to California, we started school there. We were not allowed to work in the field, so we had to go to school. So we started school there. When we went there, there was nothing they could do before we moved there.

Rosa Rodríguez: So you missed a lot of school when you were growing up? Yes. Did you graduate from high school?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No.

I just went to that fifth grade.

Rosa Rodríguez: But your younger sisters and brothers did graduate. You were the one that had to help support your family.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, all of the older ones, had to work too, to help support the whole family in. So Danielle was the first one to graduate from high school.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, what was it like for you when you had to leave school here in Idaho and go to California? Tell me if you know how it was.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, we didn't have to leave school here because we were not in school. If my father decided to go to California, he didn't even enroll us in school here. When there was no more work to be had, we loaded up and left for California.

Rosa Rodríguez: I think you had told me that you had started school here.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, actually, the first year I went to school was, at the Habra School in Orange County, but I can't remember too much. It's very hazy. And and then I did go to school here.

Rosa Rodríguez: What was the name of your who who is the best teacher here? Who would be. Who would be the the teacher that you would remember the most in your life?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I like teacher, I had a good tell us California.

Rosa Rodríguez: And what was her name?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Not just now, but she was very good.

Rosa Rodríguez: So then you're telling me that you went to school in California more than you went to school in Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, because I only come. I went to school here in Idaho. Was the winter of 39, 40. And then 40. Five. That's the year that we were going to go to California, and they didn't get the truck fixed in time. So my father decided it was too late to go to California. So we started school after Christmas vacation that year.

So we went to school here in Idaho.

Rosa Rodríguez: That. Was that a good experience for you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: It toughened us to face life's realities.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you have a language problem when you went to school here in Idaho? I know that in California, most of them were Hispanics students. Did you have a language problem here?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, we had to learn English at school because we did not speak it at home.

Rosa Rodríguez: Was that hard for you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. I think we took everything in stride.

Rosa Rodríguez: And your brothers also.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, my younger brother had a problem one time.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you go in?

Rita Padilla Pérez: He had had a teacher, Miss Muffet, that was very kind and understanding. Know the circumstances. But she had a heart attack. One time. My teacher sent me with a note to the principal's office. Looked had the sixth grade and here was coming to salt. Teacher had insisted that he stand up and say something in English. Say something. She still was reluctant, but she insisted make him stand up and say something.

So he said. But he knew. And so she was carrying him off the floor by the hair to the principal's office. I walked in behind her, and Mr. Bush was the principal. Tell her, miss, you are punishing the wrong person. She looked very perplexed, and I stood up and looked at the classroom and he said, all right, boys, all of you who have been teaching seesaw, stand up and apologize to Miss Webb.

They had been teaching. Came up behind the schoolhouse.

Rosa Rodríguez: The wrong things, Well, tell me, Rita, how much education did your parents have?

Rita Padilla Pérez: My brother was kind of a spoiled kid. His father was well-to-do. My father was very restlessly. He got expelled from school.

And they hired, They hired private teachers, and all of them gave up when my father, when they finally hired an all elderly man to teach him that, was giving my grandfather good records, but by him, by my grandfather happened to come along. And here was my father pestering the professor's horse. So. So that was the end of the education for my father.

My mother did go to school to the third grade, but in Mexico, third grade, amounts to about 10th grade. Here.

Rosa Rodríguez: They're more advanced in Mexico.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh. Very nice.

Rosa Rodríguez: So when your father was in Mexico, was that during the Mexican Revolution?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. Because he was born in 1891. So.

Rosa Rodríguez: And does he ever talk to you about them? Did he ever talk to you about the Mexican Revolution?

Rita Padilla Pérez: He didn't, but he did talk to my older oldest brother. And see, my mother told me some of the experiences they had.

Rosa Rodríguez: So did his father. Your grandfather, did he fight in the Mexican Revolution?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. He was still well-to-do. So money talks anywhere.

Rosa Rodríguez: So he didn't have to.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Know.

Rosa Rodríguez: Because he had money.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And, well, not only money, but he also had,

Authority. He was very good with the cape, with a collar. She really can handle anything and anybody.

Rosa Rodríguez: Why? How was your father? Your grandfather loved to do. What did he do?

Rita Padilla Pérez: He had learned.

Rosa Rodríguez: And, farming.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, he had people taking care of the land. All he did was collect ice and.

Rosa Rodríguez: Talking back about education, reader.

How have, education opportunities for Mexican Americans in Idaho changed in your lifetime?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Greatly.

The first thing the economy increased, I mean, improved very much since the depression was over. And then we grew up and stayed together. So we managed to talk my father into allowing the younger ones to continue school and not have to take time off.

Rosa Rodríguez: Was that hard for you to convince your father to not let your brothers and sisters go to work?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, I think we kind of gave him the alternative that if he didn't let the younger ones stay in school, what was the use of us staying home to help support them if they weren't going to get the advantage of it? Weren't.

Rosa Rodríguez: And so then they graduated from high school and went on to college.

Rita Padilla Pérez: The younger one stayed. The first one that graduated from college went to work at that Catholic plant.

Rosa Rodríguez: Do you think that Idaho's, Mexican-Americans do well in school?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Some. But I think there are a lot of them still have problems.

Rosa Rodríguez: What kind of problems do you see?

Rita Padilla Pérez: In different teachers and parents that they don't care.

Rosa Rodríguez: And the teachers? They don't care or any.

Rita Padilla Pérez: So many of them don't care. Because I remember once when one of my brothers was having problems in school and sent a note home wanting to talk to our parents. Well, our parents would never go bother to go talk to the teachers or to PTA meetings. I got the nod, but I couldn't. That's when my mother's appendix had ruptured.

I was in charge of my mother and now a two month old baby and the whole family. So I asked my sister to go talk to the teacher. My sister went. To a third grade classroom. The teacher was starting to get her own master saying expected to get just give an assignment to third graders and let them do the best they could with it while she studied for her own interests.

So when my younger brother didn't know how to read, and we didn't know it until he started junior high, and, and the reason we knew he didn't found out was because he had always, always been very good in math. And then he comes home with a report card with a you in math and so my older brother and I questioned him, hey, what's the meaning of this?

What are you doing? And he said, well, I don't understand. So he brought out his book. And here was the problem. Farmer had so many apple trees he harvested so many bushels of apples from all of them. How many bushels did he average per tree? He would have had to read to solve the math problem. And he did not know how to read any word more than two syllables.

So we cut him.

Rosa Rodríguez: He didn't understand, problem solving for storytime.

So read out when. What was your first job? That you know? I know that you have to take care of your little brothers and sisters by your parents worked in the fields. What was your first paying job.

Rita Padilla Pérez: With, in the kitchen at that old Sacred Heart hospital?

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you work in the fields with your parents before you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: But that. But that money went to the family?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. That went to the family fund.

Rosa Rodríguez: So that really would have been the first time you went to go work. How old were you when you went to work in the fields?

Rita Padilla Pérez: And as far back as I can remember, we had to pick the bias up. The potatoes.

Rosa Rodríguez: How old were you then? Did you work a whole day or.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: A whole day. And, when your parents, got paid from the farmer, did they get paid cash or check?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Usually a check. Check.

Rosa Rodríguez: And when you were at Driggs, you went also to help them when they went to go pick peace in Driggs, Idaho.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: Were you, Also working the whole day over there. And were you six years old? And also.

Rita Padilla Pérez: I was left to babysit, and, I didn't work out in the field picking green peas until I was eight.

Rosa Rodríguez: I tell you, eight. Tell me, describe to me a day, a typical day in Driggs, Idaho. After after your parents would come home from work. Were there. I don't remember if you told me how many Hispanic families there were over there. At the same time, you.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Were, about 12 altogether.

Rosa Rodríguez: How did you all get together and, no.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, we I think the men did. They said a lot, but the women had their chores to do.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, tell me about, you know, where you washed your clothes, where your mom washed her clothes.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, they dug up a well. Are in Driggs. They didn't have to dig very deep to get water either of clear, good water. So they dug well and we had to deeper bucket in to bring the water up and build a fire outside. Place stones to hold an old galvanized washing tub. And so that's where we had to heat the water.

Rosa Rodríguez: And then did the family share that water?

Rita Padilla Pérez: We had several families shared that. Well, about six families shared that well, and somebody else beluga whale part there on that.

Rosa Rodríguez: Was there only Hispanic family fair or what. They were other.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. There were also Filipinos and and Anglos, but they kind of, went up to different corners.

Rosa Rodríguez: So then when it was time for like a Saturday afternoon or Sunday, because you didn't work on Sunday at Driggs, you did work on Sunday. And I had a whole class. Yes. What was that like on a Sunday?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Catch up on the chores, do the washing and mending and ironing.

Rosa Rodríguez: And did the, parents, visit with the other neighbors and.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, yes, they would come. There was, there were two families that were particularly close, and my mother enjoyed their visiting with them very much.

Rosa Rodríguez: And,

Rita Padilla Pérez: Especially one family was from my mother's hometown. So they could always reminisce about old days.

Rosa Rodríguez: And she had someone to talk to another adult. How many years did you go to drinks?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, I don't know how long before I could remember, but from when I can remember in 1935 to 1945.

Rosa Rodríguez: And did your father go to drugs by himself before you started going? Before you were born?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I don't know,

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you ever have to celebrate? Like Cinco de Mayo or the other? My, anything like that?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I remember one thing. We were still in California, and the army celebrated, Cinco de Mayo at school, but it was just activities at school.

Rosa Rodríguez: Mama, I was referring to your family.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, not our family.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you ever, that at that little area drinks. Did, families come together and have a dance party or.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, the other families had, a lot of others had a dance just about every Saturday. But we were not allowed to leave that area for our shelter was we didn't climb up on top of the truck and watch and listen to the music.

Rosa Rodríguez: Who? When you and.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Your. My brothers and sisters. My brothers and one sister at the time.

Rosa Rodríguez: Right. Can you tell me if your father worked in the railroad here in Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, but I he worked on the railroad off and on everywhere from Pocatello to, like, food in Saint Mary's near Ashton.

Rosa Rodríguez: Yeah. I think you told me that you tape, How long? What was the length of time that he would work? How many months or how many days?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I think he had to take his vacation to work on the, potato harvest. But then, he was laid up for good when the depression worsened down. So the discrimination. So he was one of the first ones to be laid up. And after that, it was strictly farm work.

Rosa Rodríguez: For when did he first start working in the railroad?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I think from the first time he came to United States.

Rosa Rodríguez: And Idaho would be the first time that he came to.

Rita Padilla Pérez: I think he in Idaho might have been 1925.

Rosa Rodríguez: 1920

Rita Padilla Pérez: I'm not sure.

Rosa Rodríguez: Okay. So then the depression of the 1930s. You were born in 1930. And then the depression hit and he lost his job in the road.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did they tell him Hawaii? No.

Rita Padilla Pérez: But, if he was fired when he had seniority, they didn't have to give any excuses in those days.

Rosa Rodríguez: So he had been working there longer, and yet other people didn't get laid off.

Rita Padilla Pérez: He did run.

Rosa Rodríguez: So was that harder for you? Obviously it was because it was during the depression. But was he always able to find work in the farming community?

Rita Padilla Pérez: He was a good worker and so he always found work. If there was work to be had.

Rosa Rodríguez: You probably couldn't tell me very much about the depression that maybe if you couldn't remember what it was like, you know, if you struggle there, if your parents had a hard time bringing in food into the home.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, yes. Like the winter of, 36, 37, I remember there wasn't any money. In the.

We just had vegetables from the garden. Potatoes, turnips, carrots, onions. But no, no money for flour. Not even for oats. A 9 pound bag of oats cost $0.09. And we didn't have it because my father didn't have nine farms.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, did you have chickens? Well, we.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, we had had before 1934 before we went to California, but they sold everything they could sell and then came back to the house had been wrecked because my father left. It could be used for any poor people that had no place to stay. And the knocked off all the plaster up the walls and it was all greasy, dirty, filthy.

So we had nothing but our little check in the middle of the night lots when we came back, and that was all dirty. They had to scrub with lye, and even that wouldn't bring that grease off the walls. Wooden walls. So that that year, that winter of 3637, there we were with the, one of my brothers was born on December 5th, and we had nothing.

But like I said, we didn't even have beans. There had been some beans that we had been saving to set feed to chickens or a pig. Come next year, spring. But my mother got those beans because she was nursing the baby and we we stayed with up potatoes and other vegetables. And my father used to go to that butcher shop and ask for dogs.

I mean, ask for bones for the dog, which we didn't have. And he'd boil the bones in with the vegetables, which gave him a little more substance until he'd swallow his pride again to go and ask for more. But then a Mexican man family that the farmer had let them plant all they wanted had planted Mexican corn, and it came and offered it to my father.

My father said, yes, I can, you said, but I don't have any money to pay for it. And the man said, oh. You just as well you said, just leave it there for the mice to be needed. If I come back the next year, you can pay me. So we had cornbread, corn porridge, and that made life a little better.

Rosa Rodríguez: But, did you, during the depression, were your neighbors were starting more or just.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, they they were given welfare, but we were not eligible for welfare because we were Mexicans and South.

Rosa Rodríguez: And did your neighbors share with you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No way. The best they did. Neighbor across the street had, pigs. He hired my father to go and cleaned the corrals and paid him a dollar for a whole day's work. My father was delighted. He came home with a bag of flour and a bag of oatmeal.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did your neighbors tell me a little bit about your neighbors during the depression? Did they treat you well for you being one of. How many Hispanic families? One of three Hispanic families in Idaho Falls? Yes.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Others, that others went to school in Lincoln, I believe. Not that where we went.

Rosa Rodríguez: On the other side of town. Yes. How were you treated with the neighbors? How?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, they picked on us a lot these, later, the winter of 39 and 40 that we stayed here in Idaho. We had a dog. His name was Moreno. And. My mother used to let him loose. Just about that time, it was time for us to be coming home from school. And so the neighbors were afraid to. They were afraid of the dogs or the dog went to meet us at school.

So then they didn't pick up on us for fear of the dog, but they eventually killed him. And.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did your neighbors, would they come and visit your,

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. No, it was pretty much everybody stayed on their side of their fences. So it was one of those times during the depression and one of the neighbors across the alley, one in my father to give me my chicken, and my father said, why should I give you a shake? And you're getting welfare help. And we wouldn't they wouldn't give us any.

Well, the neighbor was mad enough that he put our chicken coop on fire. I found a tire and some rags soaked in gas, so we know he must have been the one, because he was so mad. Because my father wouldn't give him the chicken. And so he put our chicken coop on fire. But the neighbor across the street helped us to help my parents carry buckets of water just from the house.

So? So the house wouldn't burn along with a chicken coop.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, did you have a fire department at that time?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, yes, the neighbor called them, but, they just came and said they're jolly visiting from my parents. And the men carried buckets of water.

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh. Did you? So were the chickens lost?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, they were all dead.

Rosa Rodríguez: Tell me about, your transportation. What kind of transportation did you have here in Idaho Falls? For example? When your, dad would have to go get the groceries? What did he use?

Rita Padilla Pérez: The first I recall, we had, Willis Knight car had been quite fancy. Had, velvet upholstery inside. And I remember how my younger brother and I used to have great fun picking great green peas and feeling those great big pockets on, doors with peas. And then, that. But that car gave out. My father traded in for, one ton Dutch truck, and he built kind of a little box on the back that we were putting.

So that was kind of a part of our home when we went, camping in California.

Rosa Rodríguez: So those vehicles were there, the kind that you had to crank in the front, that.

Rita Padilla Pérez: You had to, the car. Yes. But I can remember my father having to crank the truck, I see.

Rosa Rodríguez: So your father must have worked very hard, and you worked very hard in your older brothers to be able to have a form of transportation.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, it was, essential. There was no way of getting around, especially with, discrimination. There was no finding, Right. Was anybody else? Had to be self-sufficient.

Rosa Rodríguez: Tell me a little bit about, about your older brothers. Did did, anyone have to go to, for example, the Korean War?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: Any of the wars?

Rita Padilla Pérez: My to older brother, two brothers older than I served in the Korean War. And the battlefront.

Rosa Rodríguez: How were how are your, how did your father manage when they were at war? When they were gone.

Rita Padilla Pérez: He felt very bitter because, the fact that when he went to ask for help to buy food for the ham for us, he had been told nothing for Mexicans. But when the war came, then the Mexicans were good enough to go, risked their lives.

Rosa Rodríguez: So what were your brothers? Were they in the Navy or.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, they were in the army.

Rosa Rodríguez: In the army? How long were they? How long did they serve in the Korean War?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Just about all through. And, am I, the older one of my brothers had gone to Georgia, and he was, he had trained to be, what they call medic, medic, army medic. And he had been saving all his weekend time off to come and help the family with a potato harvest. But complicated harvest time.

He was on a chip for Korea.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, this year, did he ever talk to you about whether there were more, you know, Hispanic soldiers apart from hammer?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, not so much with, my older brother. He had joined the Army, but then my other brother joined in 51, and he said there were mostly Hispanics, said there was a shipload of mostly Hispanics bound for Korea after three months of, for training at Fort or near San Francisco. And but then general MacArthur said he gave the order he did not want anybody with less than six months training.

So then they were detour to Japan, where they got another six months training. And my brother said that without those six months training, they would have been dead ducks. At the war front, Battlefronts.

Rosa Rodríguez: Rita, can you tell me, the first time that you actually started working in other areas aside from working in the fields?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, I went to work at, in the kitchen at, the Sacred Heart Hospital. And while working there in the kitchen, they noticed they had I noticed that there was, class training for practical nurses was going to be starting soon. And so I went in as the sister in charge, and she asked me up, up about my education.

And since I didn't have a high school diploma, he advised me to go work in the nursing home. And maybe between that and taking a deep test, I might be allowed to get into training program. So I went to work in the nursing home and. One of my work coworkers called me by and by that there was, a program by the state paying offering to pay for training because they had such a shortage of nurses.

So I went and took the test and tested him. And when, while I was working there, I had taken time off to help with the harvest. And when I came back, they had admitted, lady, just a couple of days before I came back that they were having problems with to a Swedish and try to insist that she did not understand English and was refusing to cooperate.

I was the same assigned to take care of her, and sure enough, when I walked in and greeted her good morning and she jabbed up some to me that I did not understand. So then I spoke to her in Spanish and she talked back to me in English. Why don't you speak English? So the card was out of the bag.

She could understand English and spoken. So we we got along fine after that.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, that was in the nursing home.

Rita Padilla Pérez: That was in the nursing home. And I did take the test and passed it, but I still had that G.E.D. to take and, after about three months in to train the training program, my supervisor told me that they still insisted that I had to take that to the test. So she provided transportation to Pocatello so I could take the test.

And I guess I learned enough helping my brothers and sisters with their homework to pass the test for you.

Rosa Rodríguez: How old were you when you took when you got your gene.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Was 28 going on 29.

Rosa Rodríguez: And so then did you get a different job?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. So I went through the training and it was rough. At one time I was almost discouraged to the point of giving up. But then I thought, since my instructor had gone through all that trouble, the least I could do was hang in there and I made it. So I worked there at the hospital LDS after I graduated.

Rosa Rodríguez: So you worked at the LDS hospital? Was there a lot of patients there that were Hispanic? Did they need your your ability to speak both languages?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Very seldom. Once in a while.

Rosa Rodríguez: I see. How did you get along? Working, at the LDS hospital? Why were you the only Hispanic?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, there was another young Hispanic girl, but we did not. We never worked together. Went to each other once in a great while.

Rosa Rodríguez: How did, nurses treat you? Out of your coworkers? Treat you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: One of my classmates had avoided me like I had, something contagious in.

That's when I. We were still students, and my our supervisor could see it, I guess. And we had instructions that usually we worked with students in each department together. And we were not to ask any of the other nurses for help when we need it. If we had a patient that we needed help with that we had to ask the other student before asking anybody else.

She assigned this other woman to student to care for a patient where she would definitely need help. And I noticed that she was kind of very reluctant just hanging around and peeking in. So I finally asked her if she needed help. So she admitted that she needed help with a patient. And so I went and helped her. And and our instructor, I think, followed that, always giving this woman patients that she had to have help with and she had to swallow and ask me for help.

And invariably we got to know each other. And I guess she came to accept me. Then after we were done with training, we were offered a class in psychology, and it came out that she had grown up in the area run Lincoln, the sugar factory, and she remember when they hit the hay at the camp of, Mexican families there to work on the sugar beets and the children.

She was a child and the children loved the music and were very curious about the comings and goings of the Mexican people. But their parents had warned them to stay away because Mexican children. So. So she had always had that, fear and apprehension of being around Mexicans. Oh my goodness. So then we could understand why you her reluctance to be be anywhere, be anywhere near me or accept me until we work together.

Rosa Rodríguez: And you got to know each.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Other, get to know each other. We were old friends. Good friends.

Rosa Rodríguez: So you were an LPN?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: At the hospital. How long did you work in the hospital?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I worked until 1965. We got a new director of nurses, and from the time she came, she was kind of breathing down my neck. And maybe some other patients had complained because, I've never been one to push my religion on anybody else, but, so many of them do. And they would always ask and try to push their own.

And I tell them to what she saw. When you have your just I have mine. And I guess I didn't like that. And I was told and warned I was not to discuss religion with the patients. And I sensed that there were some of the nurses were maybe appointed to spy on me because I could always see them kind of sneaking near the doors.

And eventually I was fired, not for talking religion, but for informing a patient of her rights. I found her crying her head up one time, and she couldn't even stop crying. She couldn't even talk. I just sat there with her until she calmed down. Then she told me that the doctor insisted she had to have a surgical procedure.

I told her, like hell you do it. Your body and you do. Or don't do whatever you want. If you don't want that surgical procedure, you don't have to have it. So they found out I.

Rosa Rodríguez: Had.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Been there and assumed that I was the one that had advised her to do as she pleased, until I was fired on the spot.

Rosa Rodríguez: So what did you do after that? Did, did you file a grievance against the hospital? And.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, at that time, there was nothing what you could do. And so I just, it was in summer. So, there was a lot of work to be done at home, and I was uncertain what to do. So I just stayed at home and did gardening and canning and made clothes for my sisters. So in the meantime, I, I got called to there was, they needed an LPN at the Sacred Heart Hospital.

So I went to work there.

Rosa Rodríguez: And that was the Catholic hospital. Yes.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And I stayed there until I went to work. Quit there to go work at the children's Hospital in Salt Lake City. I, I enjoyed working with children more than with adults.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, Rita, so you got your high school diploma?

Unknown: And you obtain an LPN certificate?

Rosa Rodríguez: Your other brothers and sisters, did they graduate from high school and go on to college?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Just the younger ones. Then who was the first one to graduate from high school? But then he went to work at, concrete plant jewelry. They go on to college and. Well, Sandra, that's next to Daniel, who died recently. She went on to college in Oregon and got her teacher's degree and title. Her life after that, until just shortly before she died.

And Julian got his degree, too. He's an insurance salesman and he was too restless, but he went to to night classes and his, pipe fitter, Alex did go to trade school. Electronics was not working as a fireman. Joséph went to college. The so majored in agriculture, but he's a bus driver at the side. Oh. Three younger girls who went to college and got their degrees or teachers.

Margie had done.

Studied Spanish in college and wanted to be a Spanish teacher. But, she even went to Mexico with a college group and spent one summer there and came back and there was an ad in the paper for, a teacher to teach Spanish in the junior high school, and she applied for the job and was told she did not have that.

She did not have the qualifications necessary. So. She applied. She went back to college and got her master's. And in the meantime, just before she finished, there was an opening for an instructor to teach the blind. So she went to work for the National Federation for the blind. And she worked for the Ed until she got married just shortly before she got married.

You know, she helps her husband in his business. And the youngest one of the girls, Lupi, went to Holy Cross Hospital in Salt Lake and got her her degree there. And he's working at the emergency. You used to work for the emergency room? I think she works in surgery now. And Tony, the youngest, went to a trade school in LA, studied welding, and he taught at that, right here in Idaho Falls for a time.

But now he's working as an engineer and doing management at the site.

Rosa Rodríguez: At, Idaho National Engineering Laboratory. You have two other younger two other brothers that dad passed away when they were babies.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. The first one was six months old.

Rosa Rodríguez: Was he born here in Idaho Falls?

Rita Padilla Pérez: He was born in California, Alta Vista in Orange County, and all came to Idaho. And then one day my mother given him his bath and went to sleep, which he usually did. But then 1:00 he hadn't wakened up. And so my mother went and try to rouse him, and he was not responsive. So they took him to the doctor and the doctor said there was nothing wrong with him.

He was just sleeping and gave him some teething lotion. But, he got worse at night. They took him to the hospital and the doctor said the baby had double pneumonia, and he was very angry that the doctor they had taken him to earlier in the day hadn't done anything else. And that was the time before antibiotics. The doctor told him his lungs were shot.

There was nothing. It could be done. They could take him home or living in the hospital. And they left him in the hospital. But he died.

Rosa Rodríguez: And was he your one year? How old were you when he was eight? You were eight. So he was one of your younger brothers. And.

Rita Padilla Pérez: And then the second one, they died. Was born in Glendale, California, in 1941. I mean, he was the most loving baby, very smart. We came to Idaho and returned to California the following winter. And the next year. We were living in a labor camp in medicine and in harmattan. The weather was very cold and rainy. He got the.

Measles and you seem to be coming along fine. We still have blankets hanging in the bed, around the bed in the corner to keep them in semi-darkness. One time he it was like I said, rainy weather and cold. We didn't let him come out of that corner. I have to stay with him most of the time. But he was such a jolly, loving baby.

It was wasn't too much. But then one time he fell asleep and I went out to the corner. I was washing diapers when it was raining outside, and there he was, standing in the doorway, laughing like a he had outsmarted me. Well, he got kind of feverish at night and got sicker the next day. He was unresponsive. But when my father talked to him, he'd always break her in smiles like his old self.

And it wasn't until he got so sick that he wasn't responding. I couldn't see him. Then my father grabbed a blanket and went to the car with my mother and my older brother following. He died on the way to the hospital. On my sister's birthday.

Rosa Rodríguez: That was that must have been very hard for everyone.

Rita Padilla Pérez: But then she had her first baby girl on her birthday, so that made it okay.

Rosa Rodríguez: Rita, what kind of responsibilities did you have aside from taking care of your brothers and sisters, what other responsibilities did you have in the home?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, my first cosponsored abilities were, along with my younger brother, we had to cut the weeds in the garden plot and rat roots anywhere would be a big galvanized washing tub full of red roots. And my younger brother and I were assigned to clean them and cut the roots off. It was a very tedious job that we hated, but we had to do it.

I've always liked the red roots. We used them before we had other vegetables.

Rosa Rodríguez: Was that, what people call Galette?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, I still like them.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did your mom make that, Galette?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. She would cook them with onions and tomatoes if we had them.

Rosa Rodríguez: So then you had to take care of the garden, and and, did you help your mom with cooking?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, well, at first I would just, help with, sweeping the floor and shelling green peas, cleaning, trimming green beans, things like that. And, Carlitos never failed. It was always an ample supply of them. And then. But when my mother got sick, that's when I really had to take over cooking everything.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, tell me about your mother getting sick. What did she. What happened?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, the first time I had to take the cooking over, I was 14 years old when Joséph was born. That's the first time I had to take over everything when she went to the hospital.

Rosa Rodríguez: And what year was that?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I was born in 1944 to learn history. It.

Rosa Rodríguez: And then. But what was wrong with her?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, at that time it was just having the baby. But then when Alex was born, her. After Alex was born, her appendix, I think she was having appendicitis attacks. But the doctors did a blood test. Her blood tests and her blood tests were normal. They would send her home with a bottle of milk of Magnesia. Had the wrong thing to do.

But she survived. And it was in 1947, just about six weeks after she had marked you, that her appendix ruptured. And so then she was in the hospital for about three weeks and had pneumonia on top of the ruptured appendix. So then I hit the baby to take her up and the whole family. And then my mother, when she came home.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you ever, get sick, Rita? Were you did you have a serious illness when you were, yes.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, that's what the rest of my education. I had been in the fifth grade in Idaho Falls for four months, about four months. And then we went to California, and I went to the sixth grade for two weeks, and I was supposed to have gone to the seventh grade because our education in Idaho is higher than California. But I got sick, I started having severe headaches and chills.

High fever soon turned out to be rheumatic fever. So that was the end of my education.

Rosa Rodríguez: At school year. At the time when you were growing up, did your parents, take you to get your immunization shots?

Rita Padilla Pérez: They gave them in school.

Rosa Rodríguez: How long were you sick with a fever?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, it was an.

It was something. Spring. We had been living in Bakersfield, and the days were hot and the nights were cold. That's when I got sick. I thought it was just a case of the flu. Very sore throat, probably strep throat. We didn't used to go to the doctors for any stomach aches or sore throats.

And we stopped. On the way home. There was a hill all covered with California puppies in bloom. It was all orange, beautiful and we took a walk up the hill and that after a while I started getting kind of blisters on the front of my legs and. And then when we got to Idaho and started bathing, I had always, been able to work and keep up with my brothers and I never complained, but this time I was hurting so bad that.

I just couldn't, especially at night. And my sister, who slept with me one time was done to me in the daytime after we got out of saying, cry baby, cry baby, you were crying and.

I had always been on the chubby side and here I was, getting skinnier day by day. So my parents finally took me to the doctor and diagnostic with my fever and.

Rosa Rodríguez: Tell me, more about your brothers and sisters. What? What would be, a typical day in the bed home with your brothers and sisters. Did they get along with each other?

Since you told me that day that your father was very strict and he didn't let you go out of your the lot where you lived, so therefore you couldn't have very many friends.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Right. Well we had our friends at school, but, I think we got along better than most children did. I see there were some,

Oh, once in a while. Like one time she saw was very careful with his clothing. Like to keep them nice. And he had gotten a new school, new coat for school. And here Danny, who was in charge of, taking care of the kindling, would start the fire in the coal stove. And the heater had used Cecil's new coat to go rummaging at the dumps for, tomato crates, then came home.

So Cecil was very, very unhappy with Danny.

Rosa Rodríguez: How did your parents discipline you? Was there a difference between the way they discipline your brothers and the way they discipline the sisters?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, yes. We all knew. So it was very seldom that anybody got disciplined, and. But the boys, picked the boys. Broke rules quite bad. I remember one time my parents were napping after the beat harvesting. I mean, bathing suits and my parents were making up for lost sleep. So there were my brothers in the neighbor's strawberry patch.

I think it was a Sunday afternoon. The neighbors must have been a church. So my brothers were over there, and I was going to join them, and they wouldn't let me. So I went and pedaled. When they were getting whipped, I repented. I wished I had paddled on there, but it was very seldom and I was.

Girls just never got the belt. We got lectured.

Rosa Rodríguez: So did you. When you were a teenager, did you go out and have fun?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, I was busy helping with the kids at home.

Rosa Rodríguez: What about your older brothers? Your older brother?

Rita Padilla Pérez: They. When there was work, they were usually too tired after putting in 16, 18 hours work to care to go anywhere. They did. My second or oldest brother at one time even played hooky from work. He went up with his friend and we thought he was going to get scalp. He came home with a bag of fish.

Fresh fish. They had gone fishing. My father was so happy to get the fresh fish for Davey.

Rosa Rodríguez: Oh, so that was good. So. So how about your younger sisters when they were, teenage, did they go out?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, they did go out only to ballgames with my brothers. But, that was all. Unless my brothers went with them, there was no going out.

Rosa Rodríguez: So then they had to be chaperon by an older brother.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, and they were just going out to have fun. Observe. But not, what you would call dating.

Rosa Rodríguez: I see. So, they went to the ballgames. What kind of volumes were there?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Baseball. Football.

Rosa Rodríguez: Did your brothers play in those games?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, one of my brothers, Danny, started. But then when he had to take time off for harvesting again all summer long where they were practicing, they decide what you call it was not, allowed to be in the team if you couldn't be there all the time.

Rosa Rodríguez: If you didn't make it to the practice. He was.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Disqualified.

Rosa Rodríguez: Tell me about your home. How many, rooms were there in your home?

Rita Padilla Pérez: In your house? Well, the original was ten by 16. And then my father ate it, before I was born. As far back as I can remember, that's where we were quarantined when we had the chicken pox and missiles in the winter of 3637. It was made up of railroad ties, kind of like a log house with, wood on the top and that dirt for insulation.

And then in 39, he added another addition to the whole front of the place. That was about 12 by 24. So that was the size of the house, very crowded. But we managed.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well. Did you have, other relatives living with you, or did you, by yourself?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, one of my father's, brothers came and live with us. Grew up. Well, there was always room for one more.

Rosa Rodríguez: And did he come to work in the potato harvester thing, beans or.

Rita Padilla Pérez: No, no, it was when we were older and he was sick when he came.

Rosa Rodríguez: I see how. What year was that? You remember?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Must have been around 50, 53, 54.

Rosa Rodríguez: And, did you celebrate as you were growing up? Did you celebrate any any or occasion like,

Rita Padilla Pérez: Generous or. No, we were far removed from that.

Rosa Rodríguez: How about, what would you do on Father's Day or Mother's Day?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Just happy Mother's Day or happy Father's Day. Than if we had the means with by some little thing for my mother.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, how long did you live with your parents?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Right up until I went to Salt Lake in 1965. I see,

Rosa Rodríguez: Did you have someone outside from the home that you, respected? Very much? Aside from your parents?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I like my father. Sister lived in California very much. And her eldest daughter, Mary, I think the world of her, she was more like a sister or almost a second mother.

Was very kind and understanding to us. And, principle that we had that day, Riverside School in Idaho Falls. Mr. Bush,

Rosa Rodríguez: The, principal at your school.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes.

Rosa Rodríguez: And tell me why you respected him so much.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Well, one winter, a boy who was, head and shoulders taller than my brother had been picking on him all through the winter. I mean, the spring, something snapped. My brother had had all he could take, and he grabbed this boy and just banged his head against the back of a tree until he was bleeding and the boy was bellowing.

Mr. Bush was up there looking out, watching from the second floor window, and he didn't do anything to stop my brother. Well, the bell rang. It was during the lunchtime recess, and that saved the boy. He went home crying. My brother went into the classroom. So here comes the boy's mother. Arena for cold means they must have had money.

Was demanding that my brother be expelled from school. Let me. Mr. Bush told her that she needed to teach her son to respect others. My brother had put up with his.

Lack of respect all winter long. So my brother had finally given him his due.

Rosa Rodríguez: Okay, what is the most important? Thing that you value in your family?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Okay.

Rosa Rodríguez: And, what family customs or values have been passed on to you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, well, we tried to get together at Christmas, New Years, and sometimes for birthdays and basketball.

Rosa Rodríguez: And family reunions. Would that be your immediate family or uncles and aunts?

Rita Padilla Pérez: No. The uncle to answer. Just about all gone. So it's it's just the immediate family, brothers and sisters.

Rosa Rodríguez: Now what about your cousins at left in California?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Oh, they've come to visit once in a blue moon and somewhere other than that, they've only come for weddings and funerals.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, Rita, I know that you, are always saying special expressions are saying. Sir, that I'm sure your father used to say to you what would be, special singing or expression that has been passed on down to, you know.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yeah, there was that one.

They sang not on a ladder. They cut me. Which means a drop of blood is worth more than a ton of flesh, meaning that those at once on race are more likely to be helpful and understanding and compassionate. But then there was also another one. Quote. No, I can you must mala el mismo palo la. Meaning there's no.

Nail worse than the one from the same one. That's meaning that, those of our own are more likely to hurt us. The worst. Whether be our own race or our own family.

Rosa Rodríguez: Do you feel that it's important to maintain the customs and traditions of your ancestors?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I think it is important, but I think it's dying out with this generation.

Rosa Rodríguez: You're talking about the generation of, your nieces and.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes, like my brothers and sisters, children are not at all interested in, Mexican celebrations, activities. They. Oh, like tortillas and tamales, but, some of them. But as far as, festivities, we don't care for them.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, Rita, you you were never married, right? Okay. So you don't have children of your own. What was the reason that you never married?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I was going to be. I was in the country for 13 months. But I got homesick.

Rosa Rodríguez: And I came home.

Rita, can you, remember the, the first, Mexican American, celebration that you attended?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I didn't really attend, but, we were living at that labor camp in Driggs. Nicholas. The 16th of September. Very unusual that, work was still going on until there we were in. So the Mexican families got together and they made, barbecue looked, cheap and pigs and the best barbecue I ever had. And they had dance and music.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, did their own workers. They played like, for example, you say they had dances. Did did they play?

Rita Padilla Pérez: They yes, they had their guitars mainly. And accordions, violins, horns.

Rosa Rodríguez: Beautiful sounds and, and the, they just dance there on the.

Rita Padilla Pérez: On the hard packed ground.

Rosa Rodríguez: Well, how has Mexican American culture changed in Idaho?

Rita Padilla Pérez: For us, not much, because we have hardly ever been partakers that I know.

Unknown: I see,

Rosa Rodríguez: How do you define yourself? Read. Do you consider yourself a Mexican, Mexican, American, Hispanic or Latino?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Mexican? My father said your mother and I are Mexican. We're from Mexico. If any of you deny being Mexicans, you're denying the mother, the parents that give you life.

Rosa Rodríguez: So how has this identification influenced you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: I'm a Mexican. If anybody doesn't like it or has no respect for me because of that, that's their problem.

Rosa Rodríguez: Is the ability to speak Spanish important to you?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. I have been able to have help a lot of people translating for them. Otherwise somebody else might not have done so.

Rosa Rodríguez: Have any of your, family members or yourself, have you experienced any, racial discrimination or other type of discrimination? And I.

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. I think that was the main mission. I was fired at the hospital.

Rosa Rodríguez: What about your, other brothers and sisters?

Rita Padilla Pérez: Yes. My brother and one of my nieces had problems at the side, and. But they were straightened out.

Rosa Rodríguez: Now, the the time you were fired at the hospital, that would probably not be a racial one. It would be a religious discrimination.