Nakia Williamson-Cloud; Trevor Bond

Topics:

The visual topic map is hidden for screen reader users. Please use the "Filter by Topic" dropdown menu or search box to find specific content in the transcript.

Doug Exton: Thank you so much for joining us for today's connected conversation. The program conducted by the IHC. If you're not familiar with our organization or the work that we do, I do encourage you to check out our website, idahohumanities.org. I would like to remind you all that you may submit questions using the Q&A feature located at the bottom of the screen.

Use many questions using the chat. I can't guarantee that we'll be able to get to them today. With me is Trevor Bond and Nakia Williamson-Cloud. Today they're going to present on the collection formerly known as the Spalding Island Collection. Turn over to you.

Trevor Bond: Great. I'm just going to go ahead and share my screen real quick.

Can everyone see that? Okay.

Okay. Thanks. So I just want to, start by welcoming everybody and thanking you all for joining us. I'm here with my good friend, Nakia Williamson-Cloud. We're broadcasting from my office studio on the, WSU Pullman campus. And Pullman is located within, the range of the 1855 treaty negotiated between Isaac Stevens and the Nez Perce tribe.

And I want to acknowledge this place that we're on. It's deep, connection to the Niimiipuu people. And I also want to just state that, I think this work and, the work that our university and Nakia and I have been doing together is important. And moving beyond, just that basic acknowledgment of the land to doing concrete, collaborations together.

So I'm going to start off, I've got a few slides to show to give you a sense of the Wetxuuwíitin’ collection and also, the archives that under, pinned, a book that I wrote in collaboration with, Nakia and his department. And then, Nakia will present, after me. So I'll just go ahead and get started here.

This is a poster that was created for the renaming. There's 21 pieces in the collection. This is the the oldest, largest, best documented, documented. Sorry, collection of, plateau material culture that survives anywhere in the world. The collection for, more than a century was named the Spalding Allen Collection. And I'll just mention a little bit about Spalding.

And then Allen, and then we'll talk about the renaming process a bit later. So here's a picture of, Henry Spalding. You know, an energetic guy, quarrelsome among his fellow missionaries, did things like bring the potato to Idaho, printing press. He also brought a stern version of Presbyterianism that really called for his followers to renounce their traditional ways, clothing, language and become a product like himself.

Presbyterian, settled farmer who wore, Euro-American clothes and spoke English and practiced that stern form of, Presbyterianism. As a missionary, in the 1840s, the the board that funded his mission really never provided enough resources for him to, be self-sufficient and to, engage in his proselytizing activities. So along the way, Spalding, like many missionaries, in other areas, took to different means to support his missionary and, what one Niimiipuu historian really described him more as a traitor at the end than a missionary because so much of his efforts went into, generating revenue and goods and, and, labor that, supported the

missionary activity. And one of the things that he did was to collect materials to send to a friend and benefactor, Doctor Dudley Allen. The two men had gone to college together. Allen lived in Ohio and, according, to the agreement that they struck, Spalding gathered up geological samples and also the material culture in the collection is those 21 pieces that I, showed you--pack them in barrels.

The barrels went down the Columbia River out to the Sandwich Islands, later Hawaii, down around, South America to Boston, and then were shipped overland by wagon to Ohio. Along with the items Spalding sent this letter. And it's a fairly detailed letter. It goes on for thousands of words. I don't expect anybody to read it. I just wanted to give you a sense of his handwriting and how he use every bit of the space, but this this area that's highlighted in yellow.

And here's a transcription of the piece. It's what Spalding estimated the value of the items were. He said that the collection as a whole. Was were somewhere between, you know, about $57.90. Now, you can see in the bottom paragraph there that Spalding really did not want, Allen to send cash. Cash was not part of the economy.

This was an economy based on trade and exchange. And so what, Spalding wanted from Allen was for Allen to send these barrels and to send tools, clothing, fine hair, silk of these goods that Spalding would use in his mission. So this exchange took place. It seemed a bit underhanded. Allen said to Spalding, let's keep our our private affairs in this barter secret, because the women read all these letters.

And Allen wanted this, collection, to adorn a cabinet, maybe in his home. And, so this is this is what happened. The the big question comes up and is, how did Spalding get these items from the Niimiipuu people? And he doesn't mention that directly in the letter. He does say where the items come from, but, there are other, parts in his correspondence where he does talk about how he, traded with the Niimiipuu for items.

It could be that followers gave these items to Spalding, and Spalding preached that wearing buckskin, wearing the regalia, was unchristian, that his followers needed to give these things up. So we don't know exactly. It could be that things were given, by his followers. Could be that things were coerced or just not sure. There's, silence in the record, but the items did survive.

This is a detail of one of two gorgeous dresses you can see here these, symbols that were repurposed just as part of the esthetic and the design in the piece and, and these, these items, these belonging to the people are gorgeous and reflect both a very ancient way of decoration using, porcupine quill work, but then also these trade goods that, that had come through an extensive network of trade that the Nez Perce, engaged in, ranging from Celilo Falls to the great fishing sites around modern Dalles, out to Buffalo Country and all points in between.

So the collection, passed from, Doctor Allen to his son, also Doctor Allen and that, doctor Allen passed the collection on to the Overland College archives. And you can see this very, minimal exception list of the collection as it came to Overland College. You can also see the kind of, minimizing, dehumanizing language there that the collections described as one lot of, Indian clothing and trinkets.

There's also, racist language around the label. Just buckskin dress for Indian squaw and language such as that. It still is part of many museum and archival collection records. And, and, there's been a movement in recent years to update and, change that language. And we made these changes here in the archives, just within the last week, going through all the collections.

So the collections at Oberlin College, the, objects, the belongings, there's dresses, the shirts, the saddle, there's there's other pieces. They go into the basement at the Wright lab on the Oberlin campus. A historian named Robert Fletcher in the late 1920s comes across the letter in the library archives. He says that he reassembles most of the collection, but not all of it.

For an exhibit. And critically, he wrote a piece in the Oberlin Alumni magazine about the collection, and that allowed, later curators, park officials as tribe members to track down the whereabouts of the collection. But unfortunately, it didn't stay on the Oberlin campus. It was sent to long term, indefinite loan to the, Ohio Historical Society in 1942.

For exhibition purposes, as far as we can tell, only one piece in the collection was ever exhibited in Ohio, and that was a cradleboard.

The other thing that we know from looking at the records, the accession records, these are much more detailed, is that, several of the pieces that are mentioned in Spalding's letter, namely bags, additional moccasins and a pair of women's leggings. They don't survive in the contemporary collection. So that's part of the ongoing work to now go back in partnership with the Ohio Historical Connection.

They changed their name. To investigate the whereabouts of these items. And Vicky has been working, with their curators there and will likely go back to Ohio as they, look for these pieces. But going back to the 1970s, Bill Holm, he was a longtime curator at the Park Museum in Seattle. He hears about the collection while he's in England.

He stops in Ohio, visits in 1976, realizes the importance of the collection, and then brings that knowledge back, and shares it with Nez Perce tribe members and with those involved with the Nez Perce National Historic Park and, the National Park Service. Negotiates with the Ohio Historical Society for a loan of most of the collection, not the Cradleboard, but the rest of it, to come here and be part of the permanent exhibits of the Nez Perce National Historic Park.

But before Ohio, agrees to the loan, they write back to Oberlin and ask Oberlin to sign away the collection to Ohio so that Ohio now owns the collection before it's loaned out. So it comes here. If anyone in their virtual audience has not been to the visitor center at the Nez Perce National Historic Park, I really encourage a trip up.

Beautifully located along the Clearwater River. And many of the items that we're talking about today are currently on exhibit. As soon as the collection comes in to the Nez Perce National Historic Park, NPTEC, the Nez Perce tribe, executive committee starts, negotiating with the Ohio Historical Society to have the collection permanently. Stay in Nez Perce country, either through permanent loan gift, or, reassignment.

But the Ohio Historical Society is not interested in that. They want to stick to one year loans, and every five years or so to have an appraisal date of the collection to ascertain value for insurance and other reasons. So when the collection was loaned, not including the Cradleboard, it was initially valued at 52,000. In 1985, Paul Rask, Northwest appraiser based in Idaho, recognized the significance that provenance of the collection and set that evaluation to $104,000 in 1993.

The price, the valuation jumps up again. And the, evaluation for insurance costs continues to climb. Given the, the age of this collection, the condition, the documentation, and also, I think a reflection of, the cultural interpretation and all the work that's been done to to interpret the collection.

So the collection remains on loan, these one year annual renewals, just keep happening. And then dramatically in 1992, Ohio Historical Society writes to the park and says, they want the collection back immediately for evaluation. At the same time, the Nez Perce tribe writes to them asking about how the collection can stay. Will Ohio exchange it for services or make a trade for collections?

But the Ohio Historical Society really will not respond, to the Nez Perce tribe. Different avenues are explored about ways to keep it potentially looking at, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act claims. The law had recently been passed, but after consultation with the highest, level at the National Museum of the American Indian, by

Allen Pinkham was the board member at the time. Yeah, Allen Pinkham was a board member. That would not be a feasible strategy in this case. And Nakia can speak more to that later on. But after a great deal of, back and forth, it's uncertain what's going to happen. The National Park Service ordered crates to send the collection back.

They made arrangements for, carrier to do it. And they also brought in, yes, experts to document the collection, elders to come in and discuss it. And, one of those individuals working on the collection is, is, my fellow and friend Nakia. And this was his first museum job. He was an intern at the time, an artist.

And he was, doing these technical drawings of several of the pieces of the collection. And these are now available online. And I'll mention that a little bit later, but this was, last chance effort to do a level of documentation for these, items would go back to Ohio. And the rumor at the time was that the Ohio Historical Society, seeing those large prices for the items, was going to sell the pieces, and they would never come back again on any kind of loan.

Details of some of, Nakia's amazing work. But, you know, individuals that is prescribed did not take this lightly. These are a key aspect of, you know, material culture of traditions, connections with ancestors. And so, the Nez Perce tribe formed, Spalding Allen Collection Committee, chaired by Richard Allen Wood. They planned a day of shame.

Allen Wood went out and spoke, to the press. The national media picked it up. Their source in the Washington Post, CBS news, New York Times, Seattle Times, the Lewiston newspapers ran a story about the campaign almost every day it lasted. And eventually, after much back and forth, the Nez Perce, tribe, reaches an agreement with Ohio to pay the full appraised price.

Of the collection plus $25,000, and agreed to a six month deadline to pay this price in full. And I just wanted to read you a little section. You know, on the one hand, if everyone thought that the collection was going and would never, come back, Allen had told reporters after this agreement reached, we were very elated, very happy, continued.

I'm glad we don't have to go into a legal battle. We ended up in a situation where no conflict will come of it. To the relief of both sides. But Allen Wood also admitted, I wish they'd just given it back to us, but I'm happy it's going to stay here. Now we have to roll up our sleeves and start raising money.

And then he also made this point. Personally, I guess we all feel sorry we have to pay for it, reflected Allen Wood. It's like paying for our own Christmas presents, but we are relieved the collection is going to remain here. So this fundraising campaign starts, and here's a detail of the cradle board and donations start coming from around the country.

The dispersed tribe hires Tom Hudson, community development coordinator, who spearheads the fundraising campaign. And one of the earliest fundraising websites gets developed. And, this is it through the Internet Archive. And one of the things that they did was take the appraised evaluation for each of the items in the collection and look for sponsors to sponsor those items at that amount.

And major donors, including the ... Foundation, Tom Redmon, and others. Potlatch Corporation sponsored major pieces. Also, you remember from Spalding's letter, he gave an evaluation of the collection at 6790 and schoolkids studying native history throughout Idaho started collecting change, having bake sales, selling privileges, challenging other schools, doing all sorts of fundraising to take a part in preserving this key part of not only, world heritage, but Idaho and Nez Perce heritage as well, keeping it in the state.

This got me kind of intrigue. A number of bands, including my personal favorite, Pearl jam, got involved. There were, public announcement ads on MTV about the campaign and PR, Kevin Peters, who was recently retired from the Nez Perce National Historic Park, and Nez Perce artists as well, designed this poster. You could receive a copy of the poster if you contributed to the campaign.

Kids sent in drawings and letters as well, with their donations. And one day before the deadline, the full amount was raised and the tribe was able to purchase the collection. And, I have just a real quick statement I'll read about, the conclusion of this. And this is from Chairman Sam Penney, the chairman of the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee.

He said at the press conference, the people of the United States have demonstrated that they value our Native American heritage. We are deeply grateful to all those who have joined us in this spirited and successful effort. We have found partners and friends. When we did not expect them, and we have seen the light and respect and compassion which suggests a greater future for our United States.

So, this all happened in, 1996. The collection was secured and then the collection has continued adding new chapters to its story. One of these is work that Nakia and I have been involved in over the last couple of years on the plateau Peoples web portal to have Nakia narrate, cultural interpretations of each of the pieces in the collection and to bring together those things, like there's technical drawings that were done in 1995, 96 to provide, a next person perspective on the collection, its construction and its cultural significance.

I worked on a dissertation. Nakia helped me through the Nez Perce tribe's, research permit process. He recorded an oral history with me and, his department, several members also, recorded oral histories that came to be part of the book. And then as publication was happening, this last fall and last spring, the tribe charged, a Spalding Allen collection renaming committee that came up with the new name that was actually to name to signify a collection that was a way and return home.

And after the ceremony, and as part of the ceremony, the committee invited representatives from the Ohio History Connection, as well as the in the Northwest Presbytery to take part. And at the time, none of the board members of the Ohio Historical Connection formally the Ohio Historical Society, had any idea about this sale. They had no contemporary knowledge that they had possession of this collection, and then they had sold it for this amount of money, and it was shocking when they looked into it.

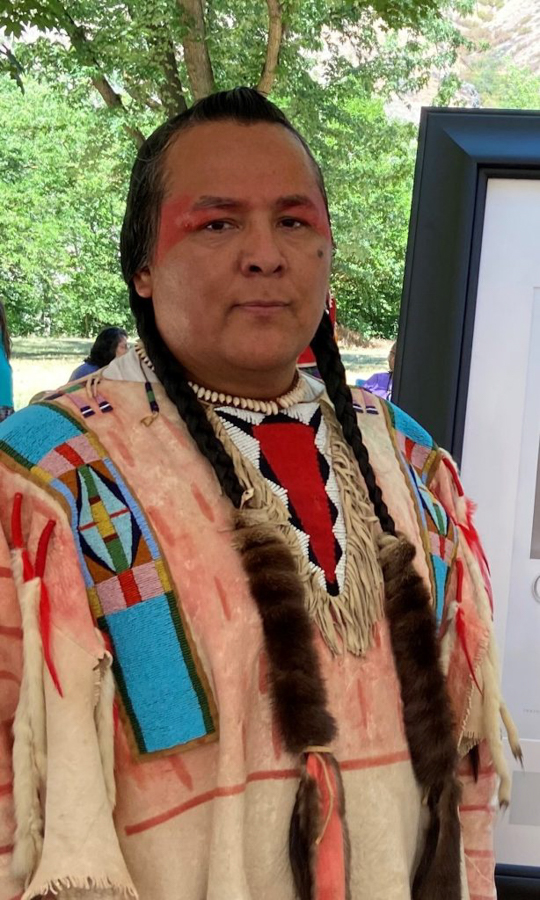

They said, a representative to the ceremony here, the renamed ceremony. And here's a picture of Nakia, and his son, taking part in the ceremony. And that started a conversation, that resulted. This is the name being given, and there's Nakia with, .... That led to an event, November 23rd, where Bert Logan, the CEO of the Ohio History Connection, came back and he's with, Chief Billy Friend, a native board member of the Ohio Historical Society to present gifts and to give a refund of $608,100.

The price paid for the collection. There were gifts exchange, including, blankets that, Nakia had designed. And it's issued a new partnership between the Ohio, history connection and, the Nez Perce tribe. So I'm going to stop there and, turn it over to Nakia to talk just a little bit about the significance of the collection.

I mentioned the price, but it's really not the price we're talking about. It's it's it's, all sorts of different, cultural values and meaning within the community about, regalia, material culture such as this.

Nakia Williamson-Cloud: I am glad to be here enjoying everybody here that has, participated virtually. This, event and this, talk to me. And Trevor has had the, good fortune of presenting on several different occasions to a variety of audience audiences. And, so it's been a it's been a really good, way to kind of recap and to try to, you know, think back of this history and as, as Trevor was given this, very good, chronological, kind of interpretation of the events that kind of happened going back from 95 to 96 and even prior to up until current day.

I think it's, it gives a time for, for myself to, to reflect as being kind of part of, you know, some of those small part in those early days of, when all this, kind of came to be and I guess, you know, for, for us, I think a lot of people outside of our community, a lot of people that don't understand the importance of these sorts of, items and collections and what they mean.

I think it's a little bit difficult to people, for people outside the culture, to really understand and grasp what these items truly mean to our people. And I think for a lot of people, the clothing that we wear, they might have some value to it, some sentimental value of something that was passed on. I think you know, even today, most of our clothing is, is doesn't have that kind of intergenerational, you know, sort of component or aspect to it.

But for us, when we dress in that clothing, the buckskin clothing, the, the items that are made for the ceremonies, and for art that help promote the lifeways of the Nez Perce people that we still carry for today. It's it represents and it's a reminder to us of our fundamental values that we have that ties us to our kinship, to our family and to our community, but even more importantly, to the land and to what we now call resources, which is a part of our life and so when we dress in this regalia, it's a reminder to what we call our tomorrow and our lore, our lore that we live by.

And those same laws is what kept us here from the time when the first treaties were signed. And we reserve certain rights, as they're known today, in terms of that federally determined identity that we've established. And the relationship that we establish would be with the US federal government. But really, what they were trying to our leaders at that time that ultimately signed that document, we're trying to preserve the same values that are represented in this collection.

And so when we view this collection, we don't view it as, just purely an X in an esthetic, you know, sort of manner, or we don't just, look at it as an art piece, even though there is a lot of artistic value, obviously, and there's a lot of esthetic value and I think anybody can appreciate, but it's a reminder to us of those fundamental laws and those values that make us who we are in terms of the the way that we're tied to everything and our elders.

We often you've heard in the past many people I've heard that our people have made these these appeals to how we are connected to the land, how we're part of the land. And I think a lot of people outside the community really kind of find that hard to grasp. Although I think there are many, many people that have connections to a place or maybe have some value or have a certain sense of feeling when they're out in the outdoors or in the wilderness area or what have you.

But for us, it takes a deeper, you know, feeling in because it's that interaction, you know? So, for instance, you know, we fish, we hunt, and and in the West, obviously there's a value of fishing and hunting. But for us it's an act of renewing that relationship, going back to the time of creation, when our people were placed on this land and the the animals and the resources, as we now understand, in today's world, are are really a significant part of our life.

They're not just the resources. We're connected to them ceremonially, spiritual in a lot of ways and even even functionally in terms of our body. And that's something that, you know, so so for us, fishing, gathering, hunting is not simply a act of recreation or it's not something that just a pastime. It's it's, a statement about who we are and how we were created and how we maintain those relationships, the rights that were established in 1855.

But, moreover, do our ceremonial and ties to these, this life that I'm speaking of, that, that we have responsibilities to the salmon, to the deer, to all these things that we share a life with to the very land itself. And it's that responsibility that makes us who we are, makes us navy blue. And so and so really, these are the things that are brought out in terms of when we view this collection.

It reminds us of, those responsibilities and, juxtaposed them with the rights that we have, you know, in terms of our federal relationship, we have via the various treaties with the United States government and and the states and the other municipalities that, and the, the advocacy that our people have provided. And so, you know, it has a much deeper sense of meaning to us, and it has a deeper resonance, you know, to us, and moreover, more specifically, I think these these items, you know, for us are a act of memorializing our ancestors, our past people.

And I think that's really hard to grasp because I can't really find a way to explain to people outside of our culture of of how these items function and still function in our community today. So when these items were taken out of our community, it was it was not only a, kind of act of, undermining that value system that I'm speaking of, but also it was, you know, it was part of the the same kind of colonialism that our people were undergoing at that time where, where our, our value system systems were being undermined by, by every institution that we as modern people rely upon today.

They were being undermined in every way possible. And so for us, the these, these items are ways in which we connect to these broader values, but but also to our ancestors. And for me, like when you see the, the, the photographs that Trevor had shown in his slideshow of of us riding on horseback when we did the renaming, we didn't do that just as a parade or just to show off.

When we do that. It's a ceremony we call ... we ride three times around the encampment. Or in this case, it was a gathering of people. And and that time we speak of the, the, the past people and in this case, even even the past people that worked to bring this, this collection back home and to ensure that it stays connected to our community and to our land and beyond that, those ancestors that endured all of what they had to bring us to the point that we are.

And so when you see me dressed up, I'm wearing the things of my ancestors that have been passed down through name givings and through other means that has been transferred to me to represent that I'm there, not only representing myself, but to my ancestors, my lineage, my people. That ties me to this place that we are standing on.

And so it's it's an act of of a certain that identity. It's a, it's an act of, of stripping away all that has happened to our people. Not that we're we are ever victims, but to show the strength and the fortitude of our ancestors that's represented through these, these items and how we bring them forth in the manner that we do it.

So when we did the renaming, I think it was a powerful way, and we tried to stick to our own ways that we feel is important. And everything we did was, it was done the way our ancestors would have, carried them out. And so that the naming was, really a culmination of many years after we acquired the collection, you know, many of the, the oldest that we had at that time that are all gone now, I think every one of them are gone.

Alan Slick .. Ricky Ellen Wood..., would you know, many of the horse accidents that you seen in the polls there? Many of those people are no longer among us. And at that time, they I especially I remember Alan Slick, who was a mentor of mine and, traditional leader and, basically that all encompassing, resource for our community.

I remember him talking about that. We need to rename we need to rename this. We don't want to call it a Spalding-Allen collection, because a lot of these collections, they, in, in the, the western modern world are named after who collective. Not not the people who they come from, which is what's important to us, which family those items are come from.

So again, it's a kind of act of erasing the past. And this it's still this continued colonial act of how we view museum collections. And that even happens today. And so I think that thought was was planted by our, our ancestors and our elders at that time. And it was with the, I think, the foresight and the leadership of our network today, especially, Shannon Wheeler, we we ought to who is our chairman and now is our vice chairman and others on our council that wanted to bring that vision to fruition.

And so when we did it, we did it in a way, because renaming is an act of reasserting that connection that we have, reasserting our identity and reasserting that connection to this place that we live, which which defines who we are. And so that was a very important, day for us. And we did things the best we could in, in, in the spirit of how our life that have carried us to the time prior to even when these items were collected, even to now that we, struggled to maintain to our language, their language, culture, identity, spirituality.

And I think it had, even those that because you could explain these things to people, you could even right now I, you know, trying to struggle to find the words you can explain. I could I could talk, you know, for hours. But until you experience it and feel there and I think that's what people felt on that day is then you get a glimpse of what we're talking about.

You get a glimpse of what that importance is. You know, you can't explain these sorts of things. You have to live it and feel it and understand it until your own self and open your own heart. And I think that's what happened on that day. And so we had, you know, the, members of the presbytery that came and gave an apology and they actually did one, several years ago at our general council in Camp Idaho.

And I think a lot of people felt felt good about that. And, and also we had Alex, we saw a representative for the I have a connection that that, you know, that originally at the time that we acquired these items were a were the, you know, the legal owners, quote unquote, owners of this collection. He was there to represent the Ohio connection.

And I think, you know, when the when they observed and were able to see this, you know, they were they were very surprised. And, there was a lot of very good and beautiful words of reconciliation on that day, which I think, the people are always interested in and doing and making these connections and reconcile the past so we can move forward as well as everybody else.

And, just that recognition and understanding that this happened, not to say that to to make anybody feel bad, but in order for you, you are as an individual, as a society to move forward. You have to recognize that this was done, you know, in the past, not not as a penalty, but as, as a way of recognition.

So you can take that step forward. And that's really what that day was about. And so there was a lot of beautiful words that were presented. And, you know, I think, you know, Alex, he was a he's a tribal person. He's a part of what to be. And so I think even the institution, the I connection has, has come a long ways.

Like a lot of institutions, a lot of society. We have a long ways to go, obviously, you know, but but they have made that transformation unto themselves. And so there was a lot of really beautiful words and talking about that. And at the time I was, I was kind of serving as the M.C. of that particular portion as we did the renaming.

And I was sitting back to listen to this, all these good words. But, I couldn't help I couldn't I couldn't, I couldn't I couldn't help but say that how much we appreciated these words, but, I had to throw it out there and say that there's one thing that we could happen, that could happen, that could help kind of minimize, maybe the pain of the past and all the things that have happened.

And. And I did mention that the Nez Perce tribe does accept refunds. And, everybody kind of got a good, good chuckle out of that one that, at the day of the renaming and, and I, I, I meant it, but I was also using humor as, as a way to get a point across as well. And, that there was something that they could do to, you know, perhaps, you know, try to bring that, bring that sense and that true, spirit of reconciliation back to everything that had happened up until that point.

And so, you know, it was a beautiful day. It was a very it was the the hottest day of the summer. I think it was like 105 that day with the heat wave we were experiencing. And so that really comment we thought that was that, that we thought that was the book into the story. But it was in October, I received a call from Brian Friend, who was on the Ohio Historical, connection board, and he, told me personally on the phone that that the Ohio connection intended on returning the money and that they were going to come, prior to Thanksgiving so that a month later and so we had

informed NPTEC and that's when you see the event happen. And I think from that, I think we had a night where, we hosted them, the desperate tribal executive committee, as well as myself. And we just shared information, with the with the, delegation that came out from our connection. Now, I think, you know, we we have a relationship with them.

It's not just this, kind of paternal relationship that often exists within institutions and tribal communities. It's a true relationship. And now we're sharing information. They've come here, and I. And I feel that, we actually, like their name implies we actually do have a connection to them. It's a true connection to them. And so, you know, we've been conversing with them.

I just got an email from Alex this morning, and, there's many more to come. And the story continues to unfold. And I think that's the beauty of, of the, of this story and what it represents to the people and also parallels the Nez Perce tribe's effort to to get back some of the land, even though we were never owners of anything, we were never owners of the land.

But in today's world, in order for us to, implement this vision that we have, that this value that connects us to this place that actually comes from the land, you know, we have taken steps to acquire property in northeast Oregon, places outside of our current reservation boundaries that were actually within the 1855 treaty. But of course, that whole history that unfolded at that time, so it goes parallel with all of that.

And so I think that I think a lot of this has to be credited to, the vision of many of our leadership. Now they really see the importance of doing these things in a proper way. Again, I mentioned a key individual we acquired who are Shannon Miller, who who's a chairman has really been a pivotal force in in creating this change and doing these things in a way that we can we can open up the hearts and minds of people to see some of these values and to see us and to recognize our basic humanity and and what and how we relate to the world around us, which is different than the broader

world. So I think it's been a very much a beautiful, relationship. And then, moreover, the work that we've done here at the Washington State University, via the Plateau People's Portal. And I think now we're starting to see the, the, the fruits of that work and those seeds that were planted long ago, in the instead of just the the base level consultation we receive, you know, from some institutions, we actually have a working relationship.

And that's what me and Trevor have been doing. And we have more work to do. And, so, you know, I think, you know, now the institutions are understanding that, that native people have have a connection and have a voice. And so now try to elevate that voice and to, to create those connections in those working relationships.

So we can we can work collaboratively and move these things forward. And, you know, I think, moreover, we have a lot to offer to institutions. And I think of institutions such as the Washington State University, recognize that and have reached out in a variety of ways to work with us. And so I think that's really where the path forward is for all institutions.

And, and really, what this really represents is that, that, transformation and that path that brought us to this point, just like the, the, collection went on this long journey, you know, down to the mouth of the Columbia, down to the West Coast, down to the, you know, southern tip of South America, back up to Boston, over with and with no intention of ever returning back to us.

Ultimately it did. You know, we're on the same journey as well. And, but at the same time looking for those opportunities to work with a partner, partner, you know, I think that's the the goal of the Nez Perce people in the tribe as, as I understand it from my leaders and the elders that have, put us on this path and hope that it will take us to a more places to come.

And so, you know, that's what I have today. And I'm glad for this opportunity to share, you know, some of the stories that we have, today and, you know, we've done a lot of these kind of presentations talking to these screens, which is not the most natural, you know, position, but, you know, hopefully, you know, some of this resonates with those that are joining us virtually today.

So ... thank you.

Doug Exton: Know, thank you, both of you, for all the insight and all the knowledge that you both contain that you shared today. Nakia I was wondering if you could talk about some of the individual items in the collection a little bit more, specifically some of the design motifs in the, you know, the cultural artwork that's part of the objects.

Nakia Williamson-Cloud: Yeah. So, the, the probably more larger, fair, they're all significant in their own way, but the items such as the buckskin clothing, the two dresses, those are similar dresses that are that still are currently passed down in our families, like, even our own family. My own family has some of those types of dresses that are actually very similar.

And so some of the values of esthetics, you see, you see that kind of undulating sort of form in the, the dress. That's not just a design and element. And so many of our elders, as it was explained to me that that part of our lore, in terms of the recognition of the animals that we relied upon and when they stepped forward and provided not only their flesh, some of them, like the deer, antelope, bighorn sheep, elk, they provided their their skin.

How we paid the maximum respect and honor to the animals was when we get a skin of an animal, we don't just cut it into square panels to make a leg in our square panels to fit into some sort of pattern that that we retain the natural elements of that of that animal. So where you see that undulating form on the woman's dress or on the bottom of that man's shirt, that's the natural outline and skin, of of the hindquarters.

And that that centerpiece is the tail with even the fur intact down to the fore legs. And and even now, I think it's, it takes as, as so many of these tan hides and work and and hunter that to skin all the way down to that point. Most people don't do that. They cut it further up above the knee.

But in order to get that shape, they had to skin all the way, basically to the dewclaw of the animal, basically to the wrist. The ankles of the deer use, utilize and and maximize and every, every square inch as much as possible of that of that animal. And so that, that fold back is the tail and behind quarters.

And then they beaded along that to create that kind of undulating, beautiful design. So in it, so in essence, the animal's creating its own design. It's not us creating this design. It's telling us that we're interpreting, you know, based on, on the actual shape of the animal that creates the design. And so that's the sort of thing you see kind of, you know, kind of represented over and over again, a lot of the different items, you know, the, the woven items, the those, cat those hats are very, associated with, not only the Nez Perce, but the Columbia River plateau.

Those are sacred hats to us. We call it ..., and they're worn only, you know. So you most people are familiar in, you know, broader society or culture of the we call it ... or the feathered headdress that represents leadership represents a certain rank in your community. And in times past, it was a very strict sort of thing of who who wore those things.

Now we wear them because they're passed down from our ancestors. So those were worn as a mark of leadership in our community, in our longhouse, especially where when we serve the sacred foods, those people that have earned that position, those women leaders, we have women leaders to not just men leaders are the ones that wear those, lead scout and, in other parts of the country, in the Plains, they don't have those sorts of things.

Those are only from here, the Columbia River plateau to the east. They don't have those sorts of items, but that's what they represent. And they're passed down generation at the generation. I have to that to my family. That was passed down from my great great grandparents, that is, kept in our family and brought out in ceremonial on time.

So, you know, there's you could I could probably speak all day on, on the collections, but that's just kind of be inside of, of, of of, some of the design elements. And I, you know, some of the esthetics and values and I think, you know, some people, may I think people see now when they see our modern, past, our powwows, ceremonies, they see the incorporation of modern, you know, sorts of, materials and things like that.

And you see that happening there with the brass thimbles, the glass trade beads. That's simply the human experience of them reflecting the world around them. And so, you know, as that world was changing, as manufactured items started to come, it was reflected in what they were doing, even though the, the core of the values were still held true in terms of esthetics and, and, and, you know, beyond this, that the reasons how those things are made, the form is still there, but sometimes the materials change and, you know, and this is something what are our ancestors part of that was not was not by choice either.

I think, you know, some of our people, when they had to adapt to the from buckskin, you know, because there was a time in the 1950s when our people were being cited for hunting, and they were being imprisoned, even my great grandfather, my grandfather, they were in prison, one time. And so, so it was sometimes difficult to get those materials.

And even now it's maybe sometimes easier because that period of time when our people were being subjugated by state laws, federal laws, and, and and so access to those sorts of things just wasn't there. And so our people, you know, tried to substitute the best that they could, given what they had at the time. But so, so, yeah, you, you see the some of that being reflected in people sometimes don't understand that.

They understand our people being like, were suspended in some idealized time in, you know, 1800s or 1700s. But we've had to adapt to changes that were forced upon us and utter, utter transformation of the landscape and and so, again, those impacts to the land and resources are impacts to us and our culture and how that gets, you know, turned around and represented, and that's I think that's just something that a lot of people don't quite, can't quite grasp.

And that's the things are why we advocate for the things that we do. Even today.

Doug Exton: Yeah, definitely kind of a reflection on how, you know, the changes in the materials are a reflection of the time that the people are going through.

And then can you also talk about the technical drawings in that preservation process that you were part of? You know, before the collection was repurchased? Unfortunately, it had to be repurchased at the time. But, you know, when there is that kind of fear that the collection was going to disappear forever and the preservation attempts there.

Nakia Williamson-Cloud: Yeah. I was, interning at the Nez Perce National Historical Park, and I think it was 19 years old when that had happened. And, you know, I think at the time, I guess, did it really quite, you know, when you're young, you don't understand about the implications of things, don't fully, quite understand, I guess. So I just, you know, it was just work that I was doing, and I had always had a connection and a knack for doing that type of work.

And. Yeah, that was we there were, there were fully documented photographs. But the curator at that time, Bob Chenowith, felt that technical drawings would have a, a more diagnostic way to represent the collection as well as an opportunity for, young people and people in a community to, to stay connected to those items. And so I spent a lot of time with, I think I did the saddle leggings and moccasins, I believe, and then a couple other piece of this in pink, did some of the women's items that Kevin Peters did, a few of the items as well.

So it was kind of a team effort. But yeah, it was with the idea that we wanted to get the ultimate documentation, thinking that we we might not ever have these items, you know, in, in our community. And I think that's so important. I think it's take home message for us. Even today, there are still other collections that continue to move out of our community and even have and important things because for for Nez Perce people, we're where one of the few parts of the country that still have these kind of items, most of them in other tribes and culture areas, all their stuff's all in museums, it's all in institutions.

It's all in collections. We still have these things, and unfortunately they have a market value. There's a monetary value in there. So there's tremendous pressures, upon tribal people to, you know, that maybe not have the economic means to sell those items. And there's, you know, that that's a whole thing unto itself. But, but yeah. So, I mean, there's a lot of these collections that are out there and, and, you know, so there's there's still a lot of, work to be done and to try and to keep a connection with our communities.

There's a shirt there that sold just a couple of years ago. That's very significant in a private collection that, you know, we've been talking about. There's other collections that were taken in 1877 that, most of our community have never seen. Some of people like myself, maybe have seen some of these items because they're back, back east or in private collections or whatever.

But I'm in a fairly unique position, but most of our community will never see these, you know, unless they're brought back. And so trying to reestablish these connections with these, these collections because of what they represent and how they're, still important to the community is really important. And and to reestablish those connections with the community is is very important because these items are, are not just, you know, like I said, art pieces are clothing.

They're a living part of our culture, and they're to to our ongoing culture and identity.

Trevor Bond: I just like to add that, Kevin Peters in, Nakia just mentioned, he talked about that, that value of really slowing down and examining the pieces he worked on. One of the men shirts and, and, did drawings of how this, you know, the sewing was done and then also counted every single fringe along the arms of the shirts, and there was a couple hundred fringes on each sleeve, but they were perfectly in balance.

And that gets at that design esthetic, too, because it's the natural form. But then there's this, this, you know, value of balance too as well. So, you know, I think that these drawings are still amazing to look at. If you go to the portal, you can see them today, but you I think an artist sees things differently than a photograph captures them.

And that sort of.

Doug Exton: And I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about the naming process as well. Especially with the new name and kind of how like and what does the name mean? And you know, how that was decided.

Nakia Williamson-Cloud: Yeah. So there was a committee that was put together and that was a part of that. There was a number of other individuals within the tribe. And, you know, we, our language department, myself and especially our elders, Bureau of Sonic, were consulted of, proper name that so that the process of naming is whether it's naming individuals places is a really important process for our people because those names really, you know, again, they kind of reflect those values in in a sense, when we name a person or place, like for instance, the the place names we have, we don't unlike the, the broader society, we don't name places after historical figures or

individuals we name places we interpret the name based on what the land is telling us. And so in essence, the land or in the case with the individual or an object in this case is naming itself based on its own attributes or characteristics. And so that name what we can mean, something that has been like taken away and return and after a long journey.

So that's where that name was felt to be appropriate. And and again, shedding the idea that, of the people that collected it and, disconnected it from the community and the land that it came from and, and, and as a way to formally welcome things back into our community, you know, we felt that that was important.

And so we did a naming, basically a naming ceremony. And that's what you see me standing there. And one of the pieces was was being held by a stasha, the lead star was being held as as we announce the name. And so we have a process of verifying with the community at large those people that were there.

And we state the name, we, announce the name three times, and then the name is repeated or repeated, and then things are being given out. And and in the process of naming people what my elders and my teachers have told me is you give to the people the furthest away that are there to, be give testimony and to, to observe and to say the name because in that way they have to repeat it.

And that name gets spread out over the land when those people return back to wherever they came from. That's how you make the name, you know, real and, and valid. And so that that kind of holds true with how our naming process unfolds. And so that's where why that name was, why and how that name was chosen.

What we did, was and so it's taken a little while to kind of get people accustomed to saying that word, and, but, but, but it's it'll be a process unto itself. But, you know, it's important for us that that we are no longer referred to in terms of the colonial past, but but what's coming now and in the future.

Doug Exton: You know, and I think that's such a beautiful process and all the, you know, the importance behind it, certainly in terms of, you know, healing and cultural identity. Unfortunately, we are out of time for the Q&A. So thank you to everyone who attended and thank you both Trevor and Nakia, for, again, all that information and insight that you were able to share today.

Trevor Bond: Thanks for hosting. It was really fun.

Nakia Williamson-Cloud: Yeah.

Trevor Bond: Thank you.