The Donald Crabtree Collection and the University of Idaho

by Tim Mace, MA (University of Idaho)

A lifetime of interest, passion for knowledge, and drive to create, lead to an extraordinary collection. Personal documents, photos, books, and thousands of lithic specimens are now housed at the University of Idaho in care of the Alfred W. Bowers Laboratory of Anthropology. How did this collection come to the University of Idaho? What kind of legacy does this provide for the lab and students at the university?

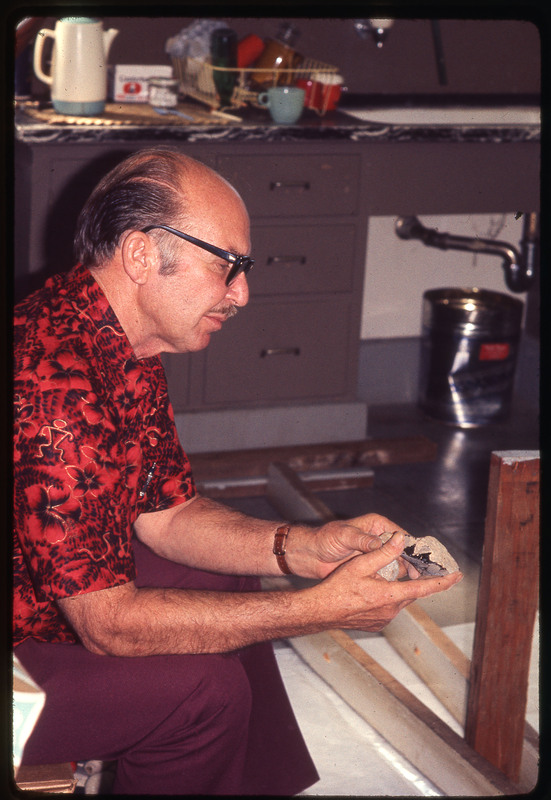

Donald “Don” Eugene Crabtree pursued a passion for lithic technology through his entire life. Born in Heyburn, Idaho, in 1912 Crabtree’s family moved to Twin Falls in 1917. Don spent much of his youth exploring south-central Idaho, including remains of prehistoric villages, contemporary Native communities, and obsidian quarries. He started experimenting with knapping during this time around the age of 10.

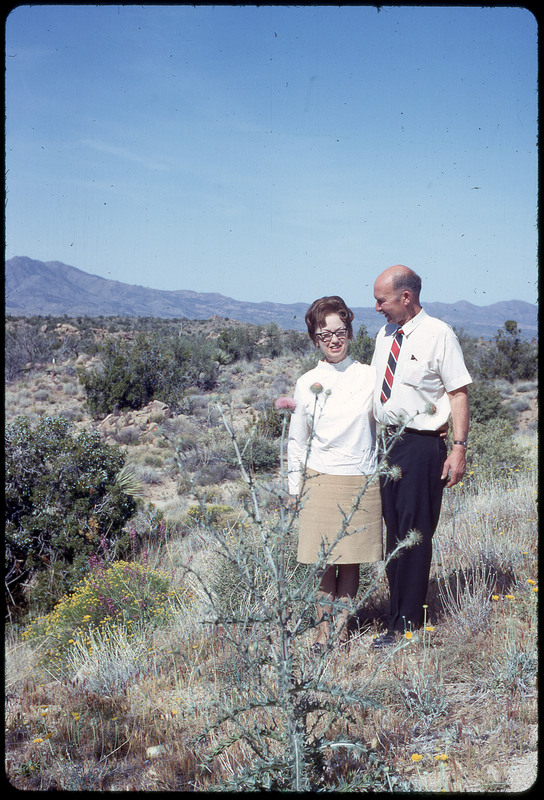

While Crabtree engaged in a wide variety of professional and personal activities, lithic technology was always something he was working on. Don did not find success in pursuing higher education. First, he found academic study at odds with his action oriented and “Thinking-while-doing” approaches (Knudson 1982). After working some time in various paleontological and anthropology labs in the 1930’s, Don was later thwarted in his pursuit of academic studies through a battle with cancer. After his cancer was in remission, he shortly found himself working for the war effort during World War Two. Despite his lack of a college degree, he is a highly regarded scholar. Throughout his life he continued to practice flintknapping techniques from all around the world as well as collect and share his insights into lithic tools and their manufacture. During his earlier life Crabtree lived in a variety of places but following World War II he moved back to Twin Falls, Idaho, with his wife Evelyn.

In 1958, Doctor Earl H. Swanson from Idaho State University (ISU) in Pocatello, Idaho contacted Crabtree after hearing about a skilled local flintknapper. The two men developed a close friendship that lasted until Swanson’s death in 1975. During this time Don worked with ISU and was able to publish much of his work and continue his lithic technology research. While Swanson received strong support for the prehistoric archaeology program he was building. Crabtree became a nationally known figure in 1962 when he gave a demonstration on flintkapping at the First Conference for Western Archaeologists on Problems of Point Typology. After a retirement on disability from his non-archaeological work, Don took an unpaid position as a research associate at ISU in 1964.

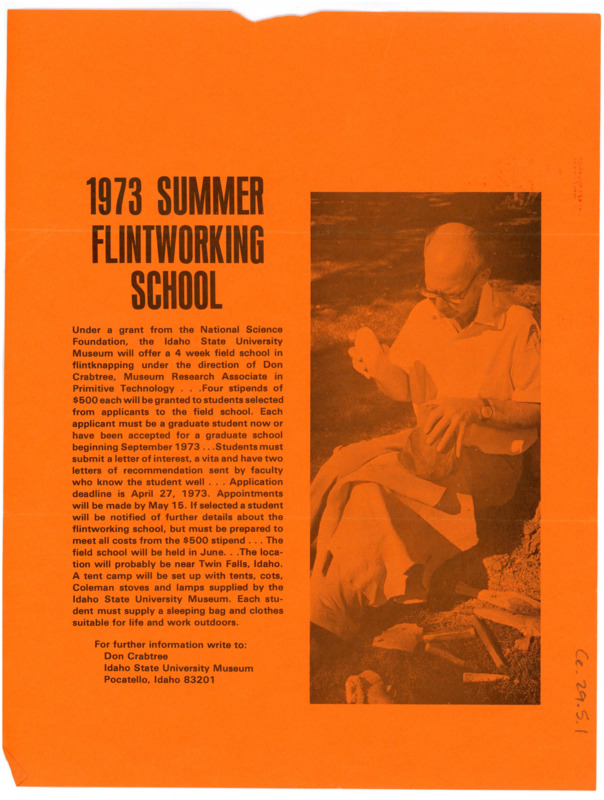

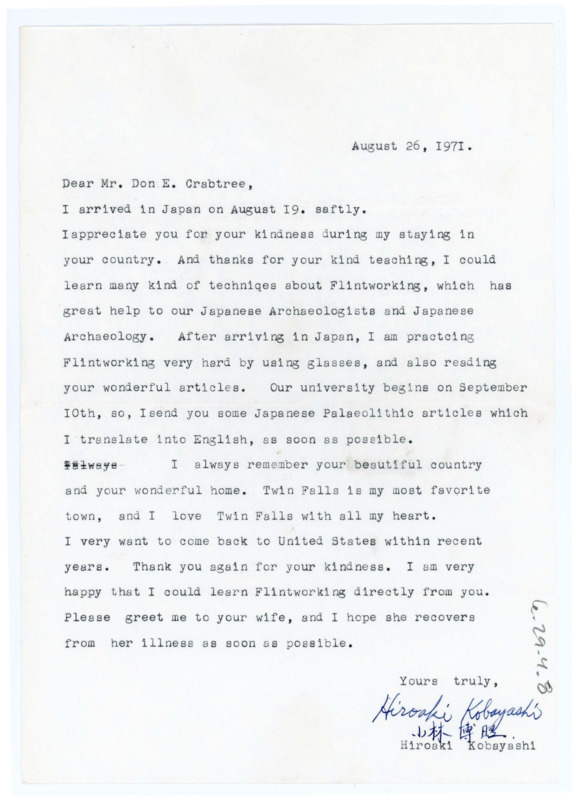

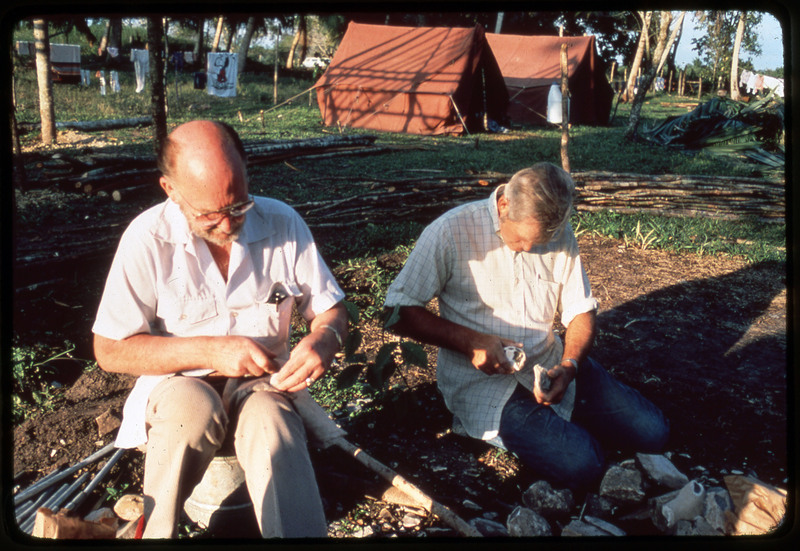

In 1969, the ISU National Science Foundation Flintworking School was established under the guidance of Swanson, with Crabtree directing. During the next six summers Don taught flintknapping techniques and ways of thinking about lithic tool production to 33 students, most of whom went on to continue work with lithic technology. Don established friendships and contacts with many of these students that lasted until his death in 1980. One of those friendships was with Ruthann Knudson; a lifelong friendship that impacted both of their careers. Much of what was taught during this period has become standard thinking regarding lithic tools and continues to be taught by students of Crabtree’s students.

After Swanson’s death in 1975, Crabtree lost his close connection to ISU. Ruthann Knudson, who was at this time teaching at the University of Idaho (U of I) in Moscow, Idaho, helped establish Crabtree as a non-salaried Research Associate with U of I in 1976. During the latter part of his life, Don moved from a more primary research position to an advisory one. U of I was physically quite distant, being around 400 miles away from his home, but provided him with institutional affiliation, telephone support, and secretarial assistance. During this time Crabtree started thinking about the disposition of his extensive collection of artifacts, papers, correspondence, and his library.

Evelyn Crabtree, Don’s wife, had kept the many papers, books, and other materials in careful order over the years until her death in 1976. Don wanted this wealth of information to be accessible to his native state of Idaho and future generations of lithic scholars. During this period Washington State University (WSU) in Pullman, Washington, had an extraordinarily strong lithics program established by Richard D. Daugherty. He decided that housing his collection at U of I would satisfy these wishes.

In a letter to Don from Ruthann dated January 26, 1978, Ruthann discusses establishing “The Crabtree Lithic Collection” a special collection at the U of I library. This was initially a collection based upon reading materials for Ruthann’s lithic course, not materials from Don’s collection. Ruthann worked with Warren Owens, the dean (unspecified who that was), and Charles Webbert, utilizing some annual library allocation and department of Sociology and Anthropology copy paper and machine.

Later in 1978, Ruthann wrote to Crabtree about thoughts regarding a scholarship he was planning to establish with part of his estate. Suggestions included expanding the potential focuses of students working with lithic technology and availability to WSU students. “…He was awarded an honorary Doctor of Sciences degree from the University of Idaho in 1980, and in celebration of the award was presented with a volume of laudatory letters from students and scholars around the world.” (Knudson 1982). This further solidified his connection with U of I and helped him fully accept the value of his academic contributions.

Working with Ruthann, Don was able to donate his collection of both artifacts and documents to the University of Idaho. Additionally, he utilized his estate to establish two annual scholarships available to students at U of I or WSU researching “stone artifacts, and diverse technologies involved, and human behavioral involvement of such artifacts, in anthropology, geology, physiology, or chemistry when related to lithic technology.”

Further and more detailed biographical information on Crabtree is accessible. The first suggested source is “Reflections in Stone Tools: A Life Story of Don E. Crabtree” by Yuumi Danner, a master’s thesis available through U of I. Secondly another great source of biographical information can be found in “Don Crabtree obituary (1982)” by Ruthann Knudson.

The Crabtree collection at U of I has 9,751 archives objects and 10,647 artifacts. The largest category of archival objects is Crabtree’s correspondence with 3,702 documents. These involve a vast variety of individuals including professional and personal contacts. Letters reveal that Don Crabtree was a warm individual that developed many genuine friendships with his students and colleagues. His archival material includes archaeological documents (1086), an extensive library (560), periodicals (638), personal documents (915), professional documents (764), and publications (163). There are several negatives (26), photographs (409) and slides (947) as well as a few other miscellaneous categories of objects in the archival materials. Many of the documents in Crabtree’s collection are rare and valuable sources for details on lithic technologies.

Don’s archive served as a rich resource for personal information both on himself and many of his friends and colleagues as discussed previously by Chloe Dame in “A Look at Donald Crabtree’s Influence on Archaeology Through his Correspondence.” There are also numerous resources for research on any aspect of lithic technology.

The artifacts in the collection are almost entirely lithic objects with only around 100 non-lithic objects, accounting for just under one percent of the artifacts. The non-lithic artifacts in this collection are mostly bone, shell, and ceramic objects. Of the total artifact collection there are 2,188 identified aboriginal objects with some artifacts of uncertain provenance. Most of the artifacts in the collection are the result of experimental archaeology and replication, by Crabtree and others. This collection showcases Don’s interest in a wide breadth of techniques and technologies related to lithic artifacts. Various pieces serve as great examples of certain production techniques. Others showcase Crabtree’s extraordinary skill and mastery with tools ranging from the minuscule (less than one centimeter) to the massive (more than 60 centimeters).

Between 1980 and 1998, rolling bookshelves, locking cabinets, and a file cabinet were purchased for use with the Crabtree Collection. The digital database that is still being modified and updated now, was created during this period. The next step was starting to think about building a website for the collection. Talks started with U of I Information Technology Services (ITS) and Center for Teaching Innovation, unfortunately it was clear that the budget required was unobtainable. These conversations did result in a list of things needed to create such a website, such as high-quality photographs. Initial work included double checking what was present and accounted for. Stabilization and photography work was the next step which lasted until about 2008.

Focus on the Crabtree collection was not forefront for AWBLA for a little while here. AWBLA was working on other projects and moving locations during this time.

In 2013, the Alfred W. Bowers Laboratory of Anthropology (AWBLA) at U of I, started reorganizing and rehousing the collection. At this time, the archival part of the collection was in disarray and unusable. The lithic specimens were in much better organization and had seen some use but were also in need of better facilities.

From 2013 through 2016 work focused on the archival piece of the collection. This work was done off and on as time permitted between other projects being done at AWBLA. Documents were sorted by type first then organized within type as made most sense for that category. For example, correspondence was sorted by names of the correspondent and dates. Documents were also prepared for archival storage by removing staples and other metal material and placing in acid-free folders and boxes. In addition to the reorganization and rehousing of materials, databases and finding aids were created to make the material more accessible and manageable. Scanning work was also done during this time of much of the archival material.

The next period of work on the collection occurred during 2016 and 2017. This was focused on the artifacts. The old database was updated, the artifacts moved buildings to a more secure and permanent home. Artifacts were also re-housed in new locked cabinets in their own locked room. Two dimensional photographs were also taken at this time.

Unfortunately, much of the scanning work and photography were not done to archival specifications. They were quite inconsistent in terms of quality and format. This has led to part of our current work as will be discussed in the next paper “Creating Digital Accessibility of the Donald Crabtree Collection” by Allison Fashing.

References

- Danner, Yuumi. 2017. Reflections in Stone Tools: A Life Story of Don E. Crabtree. Masters Thesis, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Idaho, Moscow. https://verso.uidaho.edu/esploro/outputs/996636642301851

- Knudson, Ruthann. 1982. Obituaries Don E. Crabtree, 1912-1980. American Antiquity 47(2):336-343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0002731600061229