Stanton Gilbert Fisher Collection

Writings and memorabilia of Stanton Gilbert Fisher, pioneer and Nez Perce War scout, 1840-1915

Contents: About the Collection | Brief History of the Nez Perce War of 1877 | About Stanton Gilbert Fisher | Sources | Tech

About the Collection

This collection contains writings and memorabilia of Stanton Gilbert Fisher during the time of the Nez Perce War in 1877, along with correspondence and other records from members of the Fisher family through 1988.

Materials in this collection, including images, language, or other content, may be offensive or disturbing to some viewers. Care has been taken to clearly document the sources of these records, so that viewers may consider the historical context in which they were produced. To maintain historical accuracy, the materials appear as they were originally created. They do not reflect the current views of the University of Idaho. For more information about how we treat materials with offensive or disturbing content, please see the University of Idaho Library, Special Collections and Archives Offensive Content Policy.

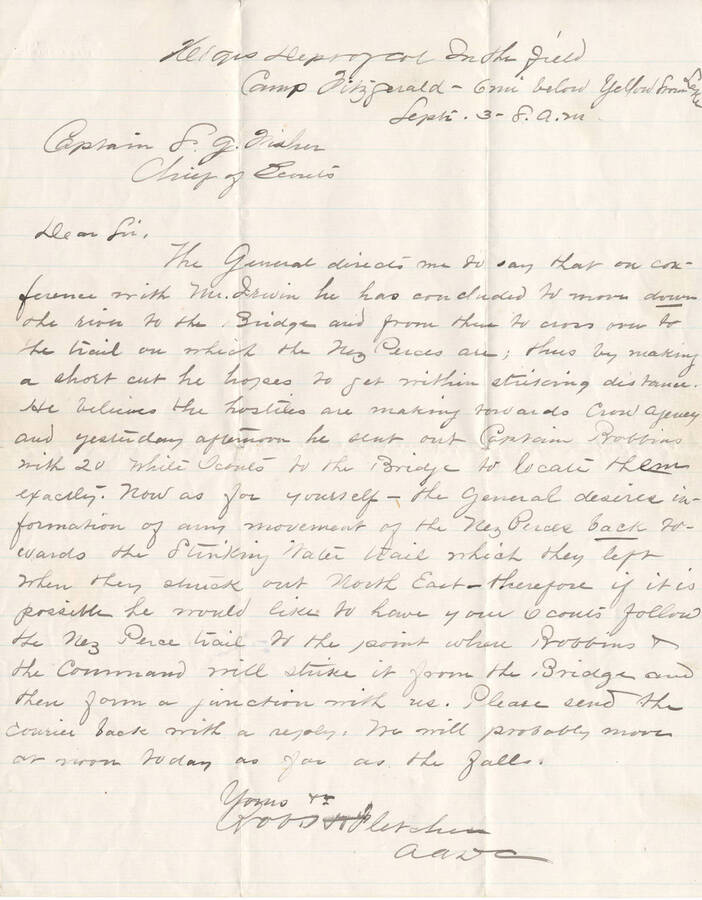

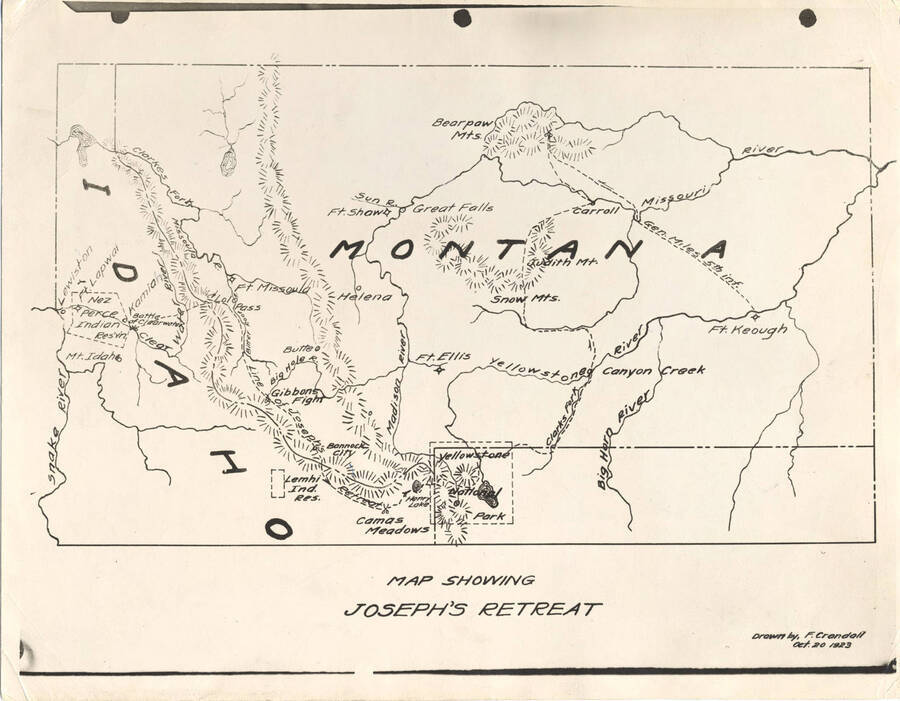

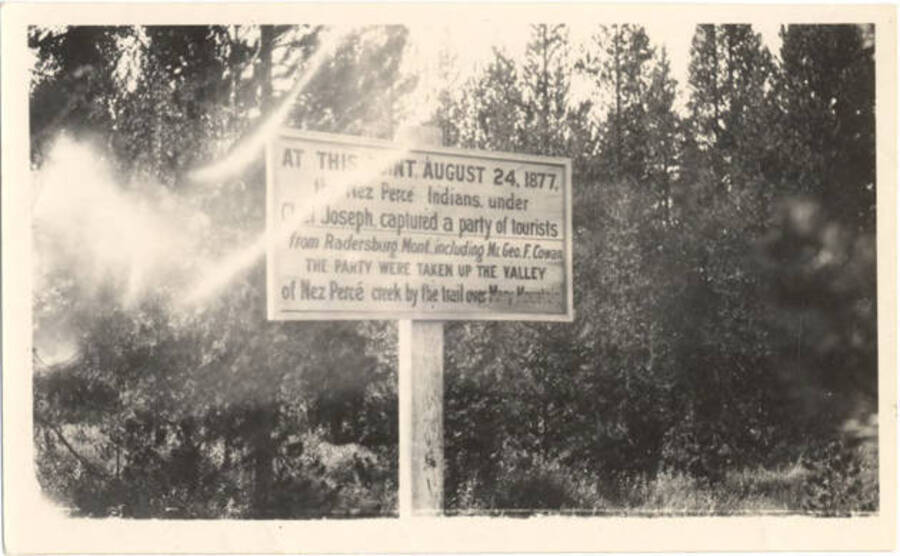

Most of the documents include maps, photographs, and written accounts of the war and its participants. There are handwritten letters from the war, maps of Idaho and troop movements, and photographs and drawings of people and places related to the war. Outside literature studying the war is also included, incorporating documents from various magazine clippings, a University of Idaho dramatic production, a small publication pieced together from firsthand accounts, a series of short stories written by one of the scouts, and newspaper articles referencing the war and its scouts.

The collection also includes personal documents related to Stanton G. Fisher and his youngest son, Don C. Fisher, such as: a trail diary kept by Stanton G. Fisher in 1888; several handwritten essays and a typed manuscript relating adventures he heard or experienced; correspondence between Don Fisher and friends of his father; an envelope from Don Fisher’s niece, Freda Terry; a receipt bearing Don Fisher’s initials; and census papers from 1880, 1910, and 1930 noting various members of the Fisher family.

Brief History of the Nez Perce War of 1877

In 1846, Great Britain and the United States settled their dispute over what they called “Oregon country.” As a result, U.S. settlers began traveling to Oregon country on the Oregon Trail and Oregon Territory was established in 1848 and Washington established in 1853.1 By that point, the Nez Perce, who refer to themselves as the Nimiipuu people, had lived in the areas now known as Idaho, Oregon, and Washington for upwards of twelve thousand years.2

In 1855, the territorial government and Nimiipuu leaders came to a treaty agreement: the Nimiipuu people would retain 7.5 million acres as an “exclusive reservation.”3 “The Nez Perce agreed to cede 7.5 million acres of tribal land while still retaining the right to hunt and fish in their ‘usual and accustomed places.’”4 In this way, the terms of the treaty “had given the Wallowa country in Oregon to the tribe, the area where Chief Joseph was raised” with the idea that the Nimiipuu people would be able to retain some of their ancestral lands.5 The treaty was later ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1859.6

However, “gold was discovered within the boundaries of the reservation” in 1860.7 “Rather than stop the squatters and trespassers onto reservation land, the U.S. government initiated another treaty council that would shrink the 1855 reservation by 90%, claiming over five million acres.”8 The Nimiipuu website describes this process as “mass trespass and theft” occurring “within the Tribe’s reservation.”9 In other words, when “gold was discovered, miners and settlers moved in, and another treaty was signed in 1863, which took the Wallowas away from the tribe.”10

Some Nimiipuu members signed the 1863 treaty and “moved to the Lapwai reservation in Idaho,” but others, such as “Old Joseph, Chief Joseph’s father, refused to sign.”11 A total of fifty-one Nimiipuu headmen “who lived inside of the proposed reservation, affixed their marks to the treaty” which was ratified in the U.S. Senate in 1867.12 “The 1863 Treaty became known as the ‘steal treaty’ and created the conditions that would eventually lead to the armed clash between the Nez Perce and the U.S. Army, now known as the Nez Perce Flight of 1877.”13 Tensions continued to mount as “a number of Indians were killed by settlers, but little was done about it.”14

“In the spring of 1877 Chief Joseph and his brother Ollokot met with General Howard on three occasions to try to avoid war and also asked that they be allowed to remain in the Wallowas. That request was denied. Several young warriors made retaliatory murderous raids against settlers along the Salmon River. Joseph and others knew that war was inevitable.”15

The war itself consisted of a series of battles and resulted in hundreds of Nimiipuu members leaving their ancestral homeland and traveling on foot and horseback over 1,170 miles through four different states.16 The war officially ended on October 5, 1877, “as Chief Joseph rode slowly up a hill at the Bear Paw battlefield to where General Howard and Colonel miles waited. The Bear Paw was only 40 miles from the Canadian border where the Nez Perce hoped to join with Chief Sitting Bull of the Sioux. Some did reach Canada, but the larger number laid down their guns with the promise they could return to their homeland, a promise that was never kept. It was where Joseph was credited with the famous speech: ‘From where the sun now sets I will fight no more forever.’”17

“The Nez Perce were promised by General Miles a safe return to the Wallowa Valley. General Miles was overruled, and the Nez Perce were instead sent to Kansas and Oklahoma, where the survivors of 1877 endured many more years of hardship. It was not until the mid-1880s that the Nez Perce were allowed to return to their homelands. Joseph and the other remaining tribal leaders spent their remaining years on the Colville Indian Reservation.”18

Despite these tensions, the Nimiipuu website says that “throughout the treaty-making process, the Nez Perce Tribe retained the inherent right to fish as usual and accustomed fishing stations, and to hunt, gather and graze livestock on open and unclaimed lands, all outside of the reservation boundary. These off-reservation rights have been upheld on numerous occasions in state court cases, citing treaty rights as the supreme law of the land.”19

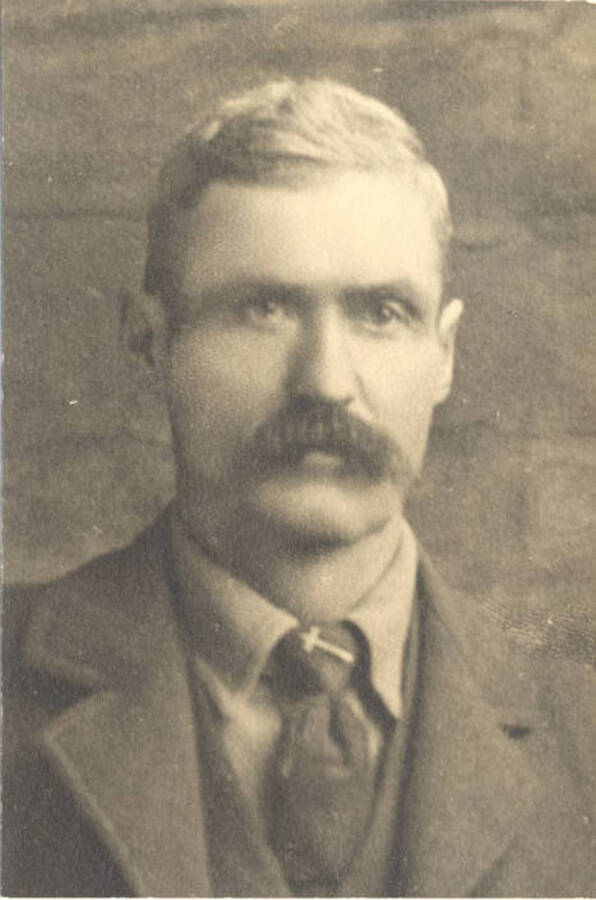

About Stanton Gilbert Fisher

Stanton Gilbert Fisher (b. 1840 - d. 1915) was a civilian scout for the United States Army during the Nez Perce War of 1877. Born in Jefferson County, New York, Fisher and his family moved to a farm in Dodge County, Wisconsin in 1850. By 1860, Fisher moved to California to try his hand at his first career, mining.

Fisher’s relationship with Idaho began in 1867 when he bought part of a trading station in Ross Fork, Idaho, which was later absorbed by the Fort Hall reservation the following year. Fisher worked as a trader and postmaster for two years before selling the outpost and traveling to Montana to participate in an annual buffalo hunt at the Yellowstone River.

When Fisher returned to Idaho, he was hired by the U.S. Army as a civilian scout to pursue a band of Native Americans that had attacked several white miners who had stolen their land as part of the 1863 Treaty, known as the “steal treaty” (see above for more information). Fisher, thirty-seven years old at the time and eventually known as “Howard’s chief scout,” organized a company of “civilian scouts,” of which he was appointed their leader.20 He led them across Idaho and Montana in pursuit of the Nez Perce. His objective, if he had found the Nez Perce, was not made explicitly clear in our sources. The U.S. Army relied heavily upon him and his men to track down the Nez Perce as they fled violence and were forced to leave their ancestral homeland, mostly because Fisher, while a “post trader for the Bannacks, operating out of Fort Hall, Idaho” became “well acquainted with the Bannacks and spoke their tongue fluently. His knowledge of both the Bannacks and Nez Perce and the region itself made him an obvious choice for Howard as a chief scout.”21

Fisher’s role in the end of the Nez Perce War of 1877 is unclear. In 1882, Fisher returned to Fort Hall, Idaho and the following year, purchased his old trading post and moved his family back to Ross Fork. He retained a trading post he had founded in Pocatello, Idaho for some time and was once again appointed postmaster of the Ross Fork trading post. However, despite these investments, he continued to travel in pursuit of mining work. In 1888, he kept a journal of his journey to a mining camp in Custer County, Idaho.

In 1889, Fisher was appointed Indian Agent for the Fort Hall reservation while also serving as Deputy Sheriff for Bingham County until 1895, when he was appointed Indian Agent for the Nez Perce Tribe at Fort Lapwai. In 1899, he departed again to pursue work as a miner in Grangeville, where he lived for the remainder of his life until his death on July 29, 1915.

The effects of the treaties, war of 1877, and Fisher’s involvement in the war are still felt today.

Sources

“Indian Country Today” is a daily digital news platform that covers the Indigenous world, including American Indians and Alaska Natives. Many people who work for the non-profit are tribal members. This source, along with the Nez Perce Tribe website, were heavily relied upon for the history of the Nez Perce War of 1877 in an effort to ensure Native voices contribute to how Native history is shaped and told.

-

“The Treaty Era,” National Park Service, December 27, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/nepe/learn/historyculture/the-treaty-era.htm. (Archived: https://perma.cc/VCJ3-LU7T) ↩

-

“Nez Perce Tribe History,” Nez Perce Tribe, https://nezperce.org/about/history/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/57CC-2BGQ); Jack McNeel, “10 Things You Should Know About the Nez Perce Tribe,” Indian Country Today, April 12, 2017, https://ictnews.org/archive/10-things-you-should-know-about-the-nez-perce-tribe/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/L5QX-5BSK); Elizabeth M. Smith, “History of the Boise National Forest, 1905-1976,” Idaho State Historical Society, 1983, 3-4, https://npshistory.com/publications/usfs/region/4/boise/history.pdf. (Archived: https://perma.cc/53LK-MNUV) ↩

-

“Nez Perce Tribe History,” Nez Perce Tribe, https://nezperce.org/about/history/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/57CC-2BGQ) ↩

-

“The Treaty Era,” National Park Service, December 27, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/nepe/learn/historyculture/the-treaty-era.htm. (Archived: https://perma.cc/VCJ3-LU7T) ↩

-

Jack McNeel, “Native History: ‘I Will Fight No More,’ Nez Perce War Ends,” Indian Country Today, last modified September 13, 2018, https://ictnews.org/archive/native-history-i-will-fight-no-more-nez-perce-war-ends/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/EEB9-XLZ8) ↩

-

“The Flight of 1877,” National Park Service, February 15, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/nepe/learn/historyculture/1877.htm. (Archived: https://perma.cc/EP6M-VQYC) ↩

-

“The Treaty Era,” National Park Service, December 27, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/nepe/learn/historyculture/the-treaty-era.htm. (Archived: https://perma.cc/VCJ3-LU7T) ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“Nez Perce Tribe History,” Nez Perce Tribe, https://nezperce.org/about/history/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/57CC-2BGQ) ↩

-

Jack McNeel, “Native History: ‘I Will Fight No More,’ Nez Perce War Ends,” Indian Country Today, last modified September 13, 2018, https://ictnews.org/archive/native-history-i-will-fight-no-more-nez-perce-war-ends/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/EEB9-XLZ8) ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“The Treaty Era,” National Park Service, December 27, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/nepe/learn/historyculture/the-treaty-era.htm. (Archived: https://perma.cc/VCJ3-LU7T) ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Jack McNeel, “Native History: ‘I Will Fight No More,’ Nez Perce War Ends,” Indian Country Today, last modified September 13, 2018, https://ictnews.org/archive/native-history-i-will-fight-no-more-nez-perce-war-ends/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/EEB9-XLZ8) ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Jack McNeel, “Native History: ‘I Will Fight No More,’ Nez Perce War Ends,” Indian Country Today, last modified September 13, 2018, https://ictnews.org/archive/native-history-i-will-fight-no-more-nez-perce-war-ends/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/EEB9-XLZ8) ↩

-

Jack McNeel, “Native History: ‘I Will Fight No More,’ Nez Perce War Ends,” Indian Country Today, last modified September 13, 2018, https://ictnews.org/archive/native-history-i-will-fight-no-more-nez-perce-war-ends/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/EEB9-XLZ8) ↩

-

David Kennaly, “The Nez Perce War of 1877,” U.S. Army, October 1, 2009, https://www.army.mil/article/28124/the_nez_perce_war_of_1877. (Archived: https://perma.cc/ZNR8-VS7V) ↩

-

“Nez Perce Tribe History,” Nez Perce Tribe, https://nezperce.org/about/history/. (Archived: https://perma.cc/57CC-2BGQ) ↩

-

Jerry Keenan, The Terrible Indian Wars of the West: A History from the Whitman Massacre to Wounded Knee, 1846-1890 (McFarland & Company, 2016), 358, https://books.google.com/books?id=AUH8CwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=fisher&f=false. (Archived: https://perma.cc/VY2F-ZW34) ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

Technical Credits - CollectionBuilder

This digital collection is built with CollectionBuilder, an open source framework for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that is developed by faculty librarians at the University of Idaho Library following the Lib-Static methodology.

Using the CollectionBuilder-CSV template and the static website generator Jekyll, this project creates an engaging interface to explore driven by metadata.