Transcript

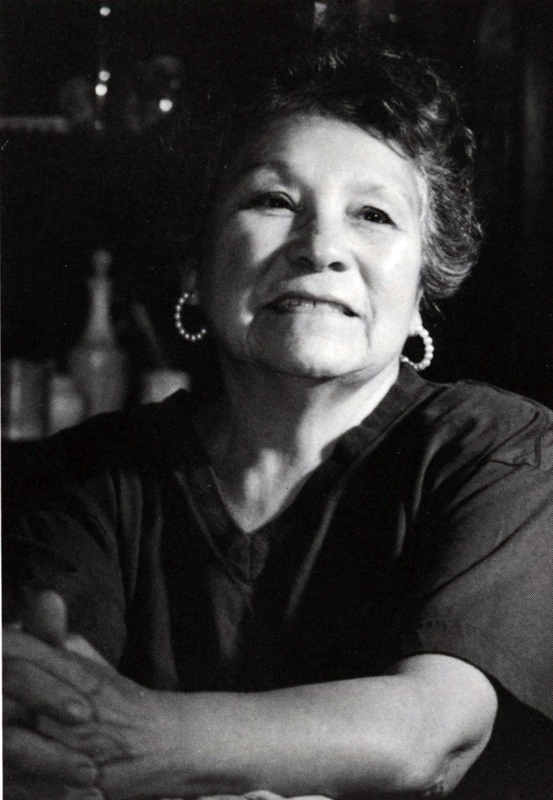

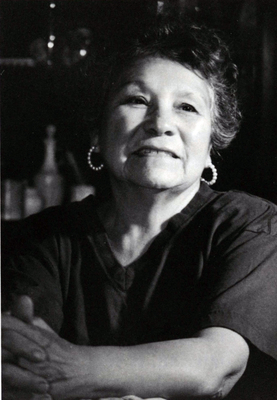

This is an interview with Victoria Archuleta Sierra by Angela Luckey for the oral history project of the Idaho Commission on Hispanic Affairs. The interview took place on January 10, 1991 in Mrs. Cierra's home, 317 South 3rd Pocatello, Idaho. Mrs. Cierra talks about her family and their experiences as they began living in Idaho. Do you know when your family came to this country?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, my family already lived here in the States. My father was born in a little town called Chaparito in the state of New Mexico. And my mother was born in a little town named Higby in the state of Colorado. And as far as I know, their people were born in the States. So I don't really know anything more about where they came from to here, except they were already there in New Mexico and Colorado.

Angela Luckey: Do you know about your grandparents?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: No, they, I think that my great-great-grandmother on my mother's side was Indian, American Indian. But I don't really know what tribe or I don't know anything about her. My mother's mother died when she was six years old, when my mother was six years old. And then so they lost track of everything. They never, she had to go live in a cattle ranch with her dad. So they lost track of everything. Nobody had ever explained anything to them. And my dad, well, his parents died when he was six years old also. So he never had any family history of any kind, except that they were all born in New

Angela Luckey: So how did your family then come to Idaho?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well my dad traveled a lot in his young days and then he finally settled down in La Junta, Colorado, and that is where he met my mother. My dad's niece married my mother's brother and that's how they came to know each other. And so they married and started having a family. I have an older brother that was born in New Mexico, because they traveled back. And then I was born in La Junta six years later. And then we moved to Grand Junction, Colorado, where he was working as a ranch man. He milked cows for this man. And we lived there until I was about six years old, six or seven years old.

And then we moved into Grand Junction, the town of Grand Junction. So from there, my dad was a field worker because he had no transportation of any kind there for a while until he bought himself a little Model T car. And then we used to, they used to take us kids to pick green beans. It was quite far out of town.

So my brother and I took care of my tiny little brother that was born in 1930. And we stayed in the car all day long waiting for them. They would come to eat lunch and we'd see them for a little while. And then they'd go back and pick more green beans until the late evening. Many a time the car wouldn't start, and so we had to be there until it was dark. So we had a few times of panic when the car wouldn't start. And it was getting dark and everybody left except us. So it was kind of, there's happy memories now. At that time it was just kind of, I would say, oh, there was lots of sad things that would happen at that time. And I can remember when we'd eat lunch my mother would boil potatoes and corn on the cob and boiled eggs. That was fun to eat lunch at that far out. It was kind of like a picnic every day. We had fun then. And we really had lots of good times.

I think about it now and it seems kind of sad that we grew up like that, but it didn't damage us any. It was just a lot of fun at that time. But we had no other means of a livelihood except my dad working out in the fields, my mother. And I learned to cook when I was ten years old because sometimes I had to stay home and take care of my two brothers while they went out. My mother and dad went out and worked in the fields. And that wasn't very easy and I wasn't too crazy about it. My dad taught me how to make tortillas and the beans were already cooked from the day before. So all I had to do was make the tortillas for when my mother and dad would come home.

Angela Luckey: It was a lot of burnt ones. Did you make the tortillas with flour or corn? Yeah, flour tortillas.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Being from New Mexico, I guess my dad wasn't too crazy about corn. They ate atole, which is corn with milk. And my mother didn't especially care to cook Mexican things, so she did a lot of, oh, we ate a lot of macaroni and stuff like that that wasn't Mexican. But she liked to, she grew up on this farm, on this cattle ranch where you didn't eat a lot of Mexican food, you know. The cooks learned how to cook, oh, they cooked biscuits and gravies and stuff like that. Puddings, my mother being a teenager at that time tried to learn how to cook all that. And she was better at cooking things like that than Mexican food. So we didn't eat much of that until we came to Idaho. And we came to Idaho in 1942 after we had been to Nyssa, Oregon. We came from Grand Junction to Nyssa, Oregon in what is called a Renganche, where they send out kind of scouts and ask if the people want to come and work in the farm work. And they pay your way. So my dad really thought that was a neat opportunity. So we went to Oregon, we went to Nyssa, and my brothers and my dad and some friends that came with us, they worked. And so my mother and I didn't have to work in the field at that time.

And we had a little sister, so my little brother enjoyed working with them, but he didn't have to work all the time. Anyway, that I mostly helped my mother. We lived in this, it was kind of a half of a house that the farmer provided us with. And there was some little other little buildings where the boys slept.

Angela Luckey: Separate from the house?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Yeah, separate from the house. And we went to the store about once a month, I guess, when the landlord and his wife went to the stores. And we went with them and bought our groceries. And we didn't have any refrigerator or anything, so we had to buy things that didn't have any chance of spoiling. So we ate a lot of canned meats and a lot of potatoes, and of course we had a huge garden at that time, so it was nice. But the weather was beautiful over there.

And then my dad had been in Pocatello, Idaho, when he was a young man. And there was only the railroad station, and the rest was really not much of anything. The Indian Reservation was where it is now, I think, or Fort Hall, because he remembers seeing Indians and even talked to some while he was waiting for his freight train so he could hop it and go back to New Mexico. He liked the weather, and he liked the way the people treated them, because in Colorado there was quite a lot of prejudice. And so we grew up kind of, I grew up kind of timid anyway because of that. But my dad always remembered that when he was here that one time, the people really treated him well. And then of course this town was just booming with people at that time, with the war and the airfield out here, and it was just lots of people. And anyway that we came here, my dad and my brothers came first, and they all got jobs on the railroad. And then my mother and my little sister and my little brother, we got here about the day after Thanksgiving in 1942.

And the people here were so nice, the Huertas, the Sazuera, the Gonzalez, that really treated us nice, took us under their wing and helped us to get settled. And they were all people from Mexico that had come from Mexico. But we just got along really beautifully, and there didn't seem to be any prejudice with the white people. The Indians came and went, and I was really surprised to see that they wore moccasins, and they wore their babies in their back on a blanket, the ladies. The men all had long braids.

They'd tuck them inside their shirts. And they spoke a lot of Indian at the time, Indian language. And it was really something for us to see because we had never been around Indians like that. Anyway, we settled down, and about a year or two later, my brother married a girl that was half Indian and half Irish. And so my dad decided that we would just stay here. He had planned for us to go back to New Mexico as soon as the war was over, and he had gathered up enough money, and he even bought a place in New Mexico. But when my brother got married, he decided that we didn't need to go clear down there anymore. We'd just stay here in Pocatello.

Angela Luckey: Was that Jose Miguel? No.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: My brother, Jose Luis, married here at that time. And then my brother had gone into the service and came back in 1946, 1947. So that's why they decided to just stay here. And we had met lots of nice people and made friends, so we just didn't feel like we wanted to move anywhere anymore.

Angela Luckey: Excuse me. Go ahead. How did your family do all the traveling when you came from Colorado and Oregon?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, when we went to Oregon from Grand Junction, Colorado, the farmer that my dad went to work for paid our way. That was a Rengancia. They pay your way to go to wherever you're going to work for these people. So that's how we got there. They paid our way. We traveled by bus, the trail way bus.

And it was kind of slow, but we finally got there. And then when we came to Idaho from Mesa, Oregon, we came to the trains. The trains were just noted at that time. It was really hard to get a seat. It was really crowded with lots of people. And when we decided to stay here, so being that Pocatella wasn't extremely large, we walked everywhere we went. And there was lots of taxis. I don't remember a bus at that time. There could have been.

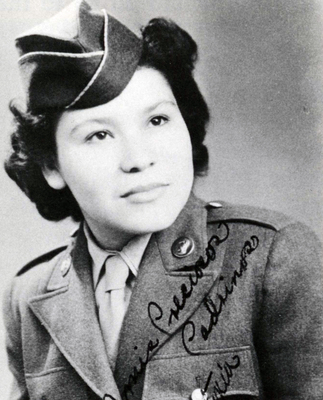

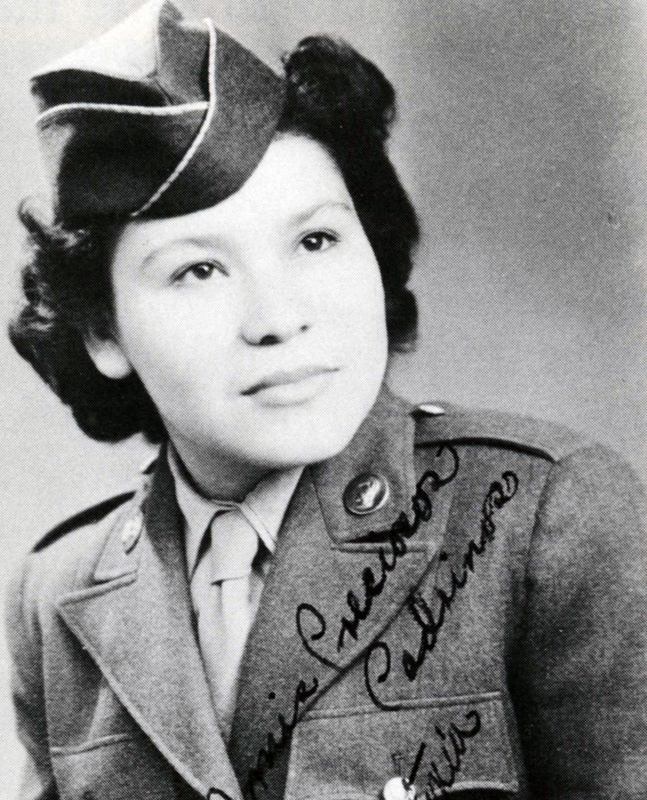

But pretty soon, my brother came back from the service, and my second brother was married and settled down. And, well, I went to the service, too, in 1945. I enlisted in the WAX and took training for hospital aid. They called us medical technicians. So we did the cleanup work, and we gave some shots, and we weren't allowed to give pills. Only the head nurse did that. And I took my basic training in Fort Des Moines, Iowa. That was really something my girlfriend and I enlisted from here. And then from Fort Des Moines, Iowa, we spent six weeks in Fort Sam Houston, Texas, learning to be medics. And once we were there and graduated from our training, myself and five other girls were sent to Hamilton Air Force Base in San Francisco, California. I was in only eighteen months the war was over by then, and they were replacing us with young men that were coming in on the draft. So I was kind of happy to come home.

Angela Luckey: How did your parents feel when you enlisted?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, I think that they were not real, real happy because none of us had ever been too far away from home. My oldest brother did a lot of traveling, too, before he went into the service. But I think that me being the only girl at that time, well, my little sister, but I was grown up. And I think they kind of worried a little bit, especially because the women that entered into the service weren't too popular for the very simple reason. The men didn't like it because they said, women's place is in the home. They don't need to be in the Army. And the people around here, of course, weren't used to things like that happening, and there were only two of us in the Mexican community that went. There were others, quite a few others. But as far as the Mexican community, we were slightly frowned on, I think. But we came back, and they accepted us all right.

And my parents were kind of glad that we had different experiences and learned how to get along with other people other than just here. And I liked it myself. When I came back, I enrolled in the, at that time, we had a Ricks, no, Links School of Business. And I attended that for a year and went to work as a waitress. I worked as a waitress for the railroad, Beanery, what they called it. It was a nice restaurant that was right there at the railroad depot. And I really enjoyed it because there were so many people coming back and forth in the trains. I worked midnight shift at one time, and really, really liked it. When the place was full of people, I enjoyed it more. But it was fun.

Angela Luckey: Where did you go shopping for groceries or clothes or whatever? Here in town?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: There used to be a store. It was home owned by these people. And they were white people. I can't remember their names. But we used to trade there all the time. My dad and the man got along pretty good, I guess. I don't know how come they knew each other. But we went there. And we used to trade a lot with credit at the time since the railroad only got paid twice a month, I think. And we used to shop there quite a lot.

Angela Luckey: So did your dad work for the railroad then by this time? Yes.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: When they first came from Oregon, he got a job right away in the roundhouse, what they called a roundhouse. And my brothers worked in different places in the railroad. I worked in the railroad too for a while before I went into the service. I worked in a place called the scrap docks. We used to pick up pieces of metal that were for the railroad cars, pick them up from one pile and put them in another pile, the good ones. The bad ones we put on another pile. So it was kind of fun. We worked outside and it was in the summer. We had fun. My girlfriend and I worked there.

And there was a little store on 4th Street run by Bill and Annie Angelos. And that was the teenage spot where everybody came together. We drank more Coke and ate more chocolate cupcakes than anybody else, I think. We'd get through working in the railroad. We'd run and take a bath and get cleaned up and come to the store to see who was there. And almost everybody was there all the time, the Morelos, the Diaz, and Joe and Dolores Diaz. John was in the service at the time, I think. And all the other kids that were around, I can't even remember their names anymore. And then when the Braceros had come into town, well, most of them worked for the railroad too. And rather than in the fields, that's really funny, they needed them mostly for the ice plant.

So that's where they worked a lot. So they were all young kids too, you know, in their 18's, 20's, 25's. That's where I met Ernie Flores and Arnaud Foil-Varez and several others, but they're the only two that I know stayed. And we all had lots of fun. Everybody was at the stores just like the corner drug store in other towns. And that's where we talked and giggled and laughed. And then from there sometimes we'd all go to a movie. And it was a lot of fun.

And down the street there was another little store run by a little Greek couple, a little man named Goth and his wife. They were always trying to teach me the Greek alphabet and how to speak Greek. And their little store was really going downhill. But they were so sweet and I don't know, I guess they died, I didn't really hear any more about them. I don't even know if they had people here or not. But they were really sweet. And they were real, real Greek, you know what I mean? They didn't speak much English at all. And it was kind of fun to listen to them.

And then later on, of course, the bigger stores, there was the big store called The People's Market. And it was, I guess it was the next forerunner of the supermarket. Because everybody went there. Of course there was a safe way and I can't remember what other store there was. There were several others, but that's where we traded the most. It was also a home-owned store.

Angela Luckey: You said the Mexicans were treated really well here. Yes.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: If there was any prejudice, it wasn't out like it used to be where I came from, from Grand Junction. In Grand Junction they even had signs up on the windows, no Mexican trade. And it was really something, you know? When we came here, that's the first thing we noticed. They didn't have signs up on the windows in the restaurants, no Mexican trade in the hotels like they did over there. And that's why my dad liked it better here. He said people were treated better here. The Indians didn't seem to be prejudiced against, you know, that the people had any prejudice against them. They walked all over in town, like I said, their babies in their backs, on their backs. And they congregated in the different corners and nobody said anything. They were always there. And that's the reason why my dad liked it here so well.

Nobody was discriminated against going to find a job at that time. While in Colorado, the only job that the Mexicans could have would be on the, what they call the extra gangs, fixing the railroad tracks. And the Italians worked like the jobs that my dad and my brothers had here, what they called hustlers and wipers. I can't remember what they were, what they were called. Anyway, they took care of the engines when they came in. They cleaned them inside and out, washed them, and helped in that turntable in the roundhouse to turn the cars around and the engines. And those jobs here were all held by mostly Mexicans. And while in Grand Junction, a Mexican couldn't get a job like that. In the Coleshoot and all those other places, mostly the Italians worked in those places. And there was, like I said, lots of prejudice. And the Mexican people from here didn't like the Mexican people from Mexico. The Mexican people from Mexico didn't like the people from here. And actually the ones that got the jobs on the railroad gang were the Mexicans from the other side because they only used to pay a quarter an hour as far as wages. And so the Mexicans from this side said absolutely not.

They wouldn't work there if that's all they were going to get. So that's why mostly the Mexicans from here, we were called manitos because we were mostly from Colorado and New Mexico. And that's where they worked mostly in the fields. Picking peaches, topping onions, picking green beans, topping beets, thinning beets, and picking apples. Things like that. If a Mexican was lucky enough to be employed by the same employer all the time, that would really be great. I remember my dad walking 11 miles to pick peaches. And like I said, we really were real poor at the time. We had no transportation. And so when this chance came along to going to Oregon, my dad really liked that. So that way we got out of town, better jobs, well better wages anyway. So that's why we came.

Angela Luckey: Did you attend school here?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, only when we first came here, I was only 18 in 1943. And so I went to ISU and took a course in electricity because I wanted to be an electrician's helper. See, they had the gun plant out here, and they used a lot of electricians and lots of electrician's helpers. I only knew very few people that worked there. So I took the course, it was six weeks I think, during the winter. I used to walk up there. My dad would walk me halfway up to the park, and then from there I'd have to walk by myself up the hill to the Votec. He'd walk you to Caldwell Park? No, not the park, well the ISU part, the ISU grounds. And then from there it would be getting lighter. So he'd just leave me there and I'd walk all the way up the hill to the Votec. There were only the three big buildings for the Votec. And there were lots of women taking courses as the electrician's helper in electricity and welding and having to do with radio, electronics, I guess it was.

Angela Luckey: He'd walk you to Caldwell Park?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: No, not the park, well the ISU part, the ISU grounds. And then from there it would be getting lighter. So he'd just leave me there and I'd walk all the way up the hill to the Votec. There were only the three big buildings for the Votec. And there were lots of women taking courses as the electrician's helper in electricity and welding and having to do with radio, electronics, I guess it was.

Angela Luckey: How did the women teach you how to work for the gun plant?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Instead I went to work for the railroad. And then I was 19, and that's when I went to work for the Beanery. And then shortly after that in 1945 I joined the service. And from there, then I went to Links School of Business where I attended a whole year and then like I said went to work as a waitress again. So I worked in a little Chinese restaurant over here on center. And then I got married. And since in those days when you got married you didn't work, you stayed home, that's what I did. Stayed home and had children.

Angela Luckey: So your earliest memories of school though, your grade school days?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, they were back in Grand Junction, yes. I went to school. I remember that my brother and I couldn't go to school until after the beet harvest because we didn't have money to buy us clothes and stuff to start school. So we started in October. I remember that because when my mother sent me with a lunch and a tablet I think. And we walked, it was a little town called Appleton from where we lived in the farm in Grand Junction. We lived five miles out of town. And the next community was called Appleton and that's where the school was. So we walked that way. Oh, it must have been a mile or so that we walked. And so they took me and all the kids that were in school, since I was the new kid, they all crowded around me and I didn't know how to speak English. So they thought I was some kind of a novelty or something.

And they talked about me in front of me, but I couldn't understand too much. But when we went in and the teacher said, sit around in the little chairs in a circle and they handed me a book. And I opened it and I couldn't imagine what that little bird was doing hanging upside down on that thing. Until the kids came around and said, no, you have to hold it this way. Then the bird was sitting right on the spout. But it was really cute because all those little kids tried to help me. And where I couldn't speak English, I would just smile, you know, and they all thought that was really neat that I couldn't speak. There was one or two more Mexican kids that I knew that were there, but they had been in school before, you know. Anyway, I had a beautiful day in school, but the teacher wrote a note to my mother and said, please not to send me to school until I learned English. So I never went back to school. Nobody taught me and my brother could speak English. He was already in the fifth or in the sixth grade. So nobody ever taught me and I never, I guess I just never asked.

So when we moved into town during the bad part of the Depression, I guess it was 1936 or something like that, 1937. Something like that. I was already about seven years old, eight years old. And I taught myself to read anyway. My dad had taught me how to read and write in Spanish, but for some reason I did not connect the Spanish with the English. Of course I didn't have much exposure either, but when we moved into the town of Grand Junction, my mother, we had a, there was this man that let his houses, his little houses out, free of rent to the real poor people. And we only had to gather up a little money to help him pay the water. And he was really nice.

And so that's where we moved because my sister's parents lived there and grandparents and they're the ones that got us the house. Well, we went into this tiny little two room house and my mother said, oh, it was terribly dirty. It was full of smoke inside. You could tell just probably bums had lived there and cooked in the middle of the floor and the walls were just full of smoke. But behind the door, there was a great big old stack of Saturday evening posts and Collier's magazines. So my mother made some paste out of some flour and water and and papered the walls with these magazine pages. That's where I learned how to read and write English because I would dope out the letters. And finally, at that age, I was already seven and eight years old. I was able to dope out the meanings with the letters that in Spanish that I had learned. It took me that long.

Anyway, I learned how to speak English and how to read. It was really wonderful because to me it opened a great big new world to me. And so that that that fall I went to school and we went to a little school called the Riverside School. It was right next to the river in a nice little there was a park and there was the railroad went right by. And this little schoolhouse only had the four grades first, second, third and fourth and the library in one room. Well, one little building was in one little building. And it was really nice. The teachers were really good.

And that's where I learned how to read better. And oh, there for a while I was the smartest kid in the first grade. You were eight years old? I was eight years old. I was smarter than all of them. I could read and write Spanish and read and write English. So that made me the interpreter for the teachers also. So it was really neat.

I really enjoyed those four years there. I was such a smart kid, except math was the thing that I wasn't too good at. But the teachers would always tell me if you would if you would get to know your math better, we would put you a grade higher. But it was too comfortable, I guess, for me. It didn't really matter. But I really enjoyed that. And then, excuse me, and then from there we had to go to school across town, which was the fifth and the sixth grade. And that's where I learned that I wasn't as smart as I thought I was because the work got harder and the children were not very friendly.

And I was the only Mexican kid in the two classes. We had fifth and sixth grade in the same room. And every time the teacher asked me what my name was, all the kids turned around and stared at me. And that made me feel kind of bad. She would say, what is your name? Victoria Archuleta. And they'd all turn around and look at me. What a funny name. And then one day we had to get up and say what nationality we all were. So of course she started with the first row and the second and third. When it got to be to me, I said I was Spanish American, Mexican Indian. And that caused a commotion. The teacher said, that's right. That's what she is. Because Mexicans have Indian blood and Spanish. And she is American. So I was the center of attention for a minute or so.

But I didn't really appreciate it because I was really shy. It was a good experience, although I was kind of timid and I did feel kind of put down every once in a while, especially when we had to walk to school with those signs everywhere. But it was all together, it was nice. And then I was in the tenth grade when we moved to Oregon. So I very slyly dropped out of school. And we were in Oregon. My dad said, you have to go to school. And I made all kinds of excuses and reasons why I couldn't go. So I didn't.

So after we came here, I went and took that course in electricity. I got really good grades. And I used to make up some of the neatest connections at home with the lights and the lamps and the radio. It's a wonder I didn't electrocute myself. But I did used to really like it. And then I went to Links School of Business after I came out of the service. And I got good grades there too, only I didn't do anything with them. I just went to work as a waitress.

Angela Luckey: But years later then you took the course in child?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Years later, when my, let me see, I had already had eight children. I had always said that when I send my last child to school, I was going to go to school. Because I wanted to be a teacher. Well, in the meantime, after my, let me see, I had six children. And then four years, yeah, four years later I had another little boy. And the reason I didn't go to school after that was because I went to work in the hospital.

I worked in what was called the central service supply. And where we worked with autoclaves and we sterilized water and instruments and stuff like that. And since I had been in the service, they asked me to go and work there. I had a friend that asked me to go to work there. So I didn't pay much attention to going to school anymore. But in the meantime, I had had my seventh child, and that maybe died. He was two years old and he died. And I was still working in the hospital at that time.

So I immediately thought I had to have more children, so I had two more. And so the others had all gone to parochial school. So when I had these other two, I didn't send them to parochial school. We started out in Head Start. I sent my first little girl the Head Start, and everybody had to put in ten days in Head Start, the parents, to help their children and help whatever. So I went and I really liked it. I thought, wow, this is the closest to a teacher I'll ever get. So after I put in my ten days, I asked the director if I could keep going back.

Angela Luckey: And she said, yes. So I did. I kept going back.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: And when Elisa, my next to the last child, went into the elementary school, I had the lorry at home. So I went with her. And they finally decided to employ me. They started paying me for going, so. But I really enjoyed it. And there I took lots of training for, even, was able to get a, what was it, a CBA certified children's, what? Child Development? Yeah, it had to do with child development. And it was in accreditation, what do they call that? What is that? Associate degree. Associate degree, yeah. And I got that. And like I said, I really enjoyed it. I think I worked fifteen years that I got paid for fifteen years working there. But, oh, it was about a year before I retired that I started working just part time.

But they used to call me a lot. They used to call me, even after I retired, I went back several times when they needed me. I had asked them that if they needed me, you know, I could go. So I did. I would make my time, work my time around so that I could go and help them. And like I said, I really enjoyed it. But when my husband retired, I retired also. So now I'm just a grandmother and a great-grandmother.

Angela Luckey: I'm going to back up a little bit. When you were talking about living in that housing place where the man was realizing he gave him some money to help you with the water. You mentioned that your sister's parents and grandparents got you in there.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, my sister's grandparents had three children, two girls and a boy. And the reason we met them was because they were thinning beets across the road from where we lived in the little farm in Grand Junction where my dad took care of the cows and milked them and all that. They had to help process the milk. And they were working their topping beets. The boy was the same age as my brother. So he kept going back and forth taking them water and sandwiches. And then in the evening he invited them to come over. They had two girls and one boy. So he was just about 14 or 15. So something like that. Anyway, that he brought them over to meet my mother and my dad. And so they became really good friends. So we used to go visit them. Oh, every other Sunday we would go into town and visit them. Every other Sunday they'd come out to visit us at the farm. So we got to be real good friends.

And so, well, the oldest daughter got married and the youngest daughter got married. And then they all, at this time, we went to live in Grand Junction in the town because the farmer had lost all his farm and everything. During the Depression he couldn't pay my dad anymore. So we moved into this little place where my sister's grandparents asked him if we could live there. So we went there. We lived about three yards away from each other. And so we were always constant friends. And when the girls got married, of course they started having children. And each time that the one, her name, the oldest girl's name was Patsy. The second one was Ramona. And the boy was Gilbert. And the grandmother was Pomocena. And the grandfather was Marcial. He was part Navajo Indian. Anyway, the girls got married and started having children. So Ramona, the second daughter, would ask my mother and my dad to baptize the babies. Well, they had one and it died. And they had another one and it died. And the third one lived to be four years old. But then he died.

So they had another little boy. And he was two years old when my sister was born. When they had the baby girl, the mother, Ramona, was suffering of tuberculosis. And she was very, very sick. And the doctor had told her not to have any more children. Well, she wanted a little girl. All those others that had died were little boys. And the one that was living was also a little boy. So it's funny that they were such good friends. And one day my mother said, oh, I would like to have one more baby girl. Because all they had was me. And I was a tomboy. So she said, I would like to have one more baby girl. And of course, at that time, Ramona said, well, don't worry, Florencia. I'll have a baby girl and give it to you. Everybody was healthy and well and happy. And they just laughed about it. Sure.

She used to play paper dolls with me, and she used to teach me how to bake. She sewed beautifully, and she embroidered. Oh, she was really talented. And I really was attached to her quite a bit. So I always said that if I ever had a little girl, I was going to name her Ramona, so I did, my oldest daughter. Anyway, that they would not adopt the baby legally to my mother and dad. But when we went to Nyssa, Oregon, my dad and mom, of course, asked permission to take her with them. And then, of course, eventually he got married and had family, and he had kept the boy with her brother. And so that's how come we got a baby sister. I was 14 years old, and my two brothers were younger, and we just doted on that baby. We just spoiled a rotten, that was all there was to it. She's 50-some-odd years old, and she's still spoiled. So it was really wonderful for us, because we really thought that was neat.

Well, it seemed like after all this time when she did have that baby girl, Ramona was very, very ill. And she was not supposed to have any more children. But since she did have that baby girl, the doctor said that she was not going to make it. And so the baby was 15 days old when she and her deathbed told her husband that she wanted my mother and dad to have that baby. And she said, anyway, it's not going to live very long, the doctor said. And see, her mother and dad were too old to take care of a tiny baby. Her sister had about six of her own already. And her husband's family weren't able to take care of her. So she wanted my mother and dad to have that baby. So we see, and they named her Eleanor Vivian. And of course, their last name was Carvajal. Anyway, my mother and dad baptized her and brought her home with them about three yards away, brought her home. And then three months later, well, three months from the time the baby was born, the mama died, Ramona. I always used to say that when I had kids, if I had a girl, I was going to name her Ramona too, because I really liked that lady.

Angela Luckey: You've done a lot of kinds of work. Were you always paid in money, or were you paid otherwise?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Oh, you mean for when I worked for the railroad? For all the different jobs you've had? Yeah, we got paid. Well, I was on the railroad payroll twice, because I worked for them out in the scrap docks, and in the roundhouse at times. I swept the roundhouse, and then I worked as a waitress in their beanery. And it was at different times that I did, and I was on their payroll. And your parents got paid? Oh, yeah. So there was no kind of trade? No. No, and we traded in the stores. Like I said, we had credit in the stores. We didn't pay money right away. But in Grand Junction also, when my dad worked out in the fields, yeah, they got paid money. They could take some of the produce if they wanted to, but I remember those great big beautiful peaches my dad used to bring home. Gorgeous. They were so good. And apples that they bring. Yeah, it was really, there wasn't much money, but they did get paid.

Angela Luckey: Were there any differences in the way that the men were treated and the women were treated in your jobs, in the different jobs you did?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: When we first started working in the railroad, there were lots of women working in the railroad already because of the war. But they weren't treated differently at that time because they were needed, I guess. And actually, it was kind of a have to kind of thing because there were sending so many able-bodied men out to the services. And there were lots of older men working. You know, my dad was in his 50s and 60s at that time. And there were quite a lot of older men and women also, like there were lots of young ones too. But this railroad here was such a big place and such a central point out here. There was lots and lots of people, lots of workers, three shifts at night. So it was quite crowded, like I said. There was the braceros that came in from Mexico and the airfield out here. And that was it.

In Nyssa, Oregon was where they had a camp for the Japanese people. You know, they gathered all the Japanese Americans and put them in a camp. They weren't very well treated. But here in Pocatello, I didn't notice any of that. I understand they had a German camp somewhere, but I didn't, of German prisoners, but I didn't, don't know where.

Angela Luckey: It was just your family that lived in the household, or was there anybody else, your grandparents?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: No, my grandparents on both sides died when my parents were real young. But there were about three boys that came with us from Grand Junction in the same, oh there was lots of people that came from Grand Junction, but three boys that wanted to work with my dad because my dad only had the two boys, and they wanted to work with him. So they lived with us. That was Felix Gonzalez and his brother, Pifi Gonzalez, and another boy, oh there were two others, but I can't remember their names. But the ones that stayed with us, yeah, there were Pifi and Felix, which stayed with us all the time even when we came to Pocatello. So they're kind of, we regard each other as family, you know. They stayed with us all the time.

Angela Luckey: And did your dad own his house where he lived in Pocatello? Not at first. This house he bought.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Oh yeah, he had a house up on North Third. Yeah. They bought that house right after I went into the service. They bought that house, and they lived there until 1955. And then they bought this house. And that was quite something because my dad had bought some property up in New Mexico, and we were going to go back to New Mexico and build a house there. He was going to make it out of Vadobis like everybody else had a house like that. And it was really neat to think about, but then we never did go. He sold the property, and so he bought, that's when he bought the house here, up on North Third by the flour mill.

Angela Luckey: So what would you say is the most important thing about Pocatello to you?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, everybody has an opportunity to do what they want. You know, there's education, there's ISU. My brother graduated from ISU, and I took classes there a lot. And like I said, some of my grandchildren will be there. My children attended one year each, I think. But the opportunities in Pocatello are, I would say, pretty good because I always felt that we were pretty well accepted here. And we're not real, real poor, but maybe we're not completely middle class either, but it makes for a pretty comfortable life that we've had here. And in case there is any prejudice, we have learned to kind of defend ourselves. We aren't timid like we used to be, and I brought my children up that way. When anybody called them names, I would tell them, you tell them, well, that's all right. I might be a Mexican, but I'm not dirty, and you might even be dirtier than me. But in good words, I never let my children fight. My brother used to get mad at me because he'd tell me, you're teaching these kids to be nothing but sissies and not fight. I said, no, that's not my way, and I don't want them to fight. If they're going to come up against prejudice because somebody doesn't like them because they're Mexican, well, that's those people's problem, not my kids. Because they have been taught to respect other people. And of course, they never lived among that kind of stuff like we did. We used to have people calling us all kinds of names. Of course, we weren't very nice sometimes either. We'd call them back. So we lived around a lot of Italians, and of course, what we called gringos. But the prejudice was never anything here like it was back there. So this is why I have always liked Pocatello, and I'm planning to stay here.

Angela Luckey: And you've lived in this, your mother lived in this house?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Yeah, my mother and dad bought this house and the property in the back, which was my house, I raised six children over there. And of course, they had the run of grandma and grandpa's house. And then when my dad died, my husband and I and my last two little girls came to live in the basement apartment of this house. And we didn't stay much in the basement department. We stayed up here most because my mother was alone. And then eventually all the kids were there. Well, my children all kind of moved out and got their own jobs and had their own places to live in. So there was only the two last ones. There were six big ones and two little ones. And Elise and Lori were the little ones, and they were just going to grade school when all the others were grown up already. And eventually some got married, like I said, and some are still single. And we lived back and forth with my mother, and my sister finally decided she wanted to live in the house in the back where I had lived. So when my mother died, the house was mine, you know, and the little house back there is my sister's. So we've gotten along pretty good and never lacked for anything.

Angela Luckey: Do you recall any special scenes or expressions that were used in your family? Oh, yes.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, my mother used to, when she would get really irritated at something, she'd say, I don't know what it means, but she would always say that. And the kids always remember her saying, which was really funny to them. They didn't understand what it meant, but they still remember it now, and they always tell each other that. But, oh, yeah, my dad had lots of sayings. I can't remember right now what they were, but he was always a real mellow type of man. However, he had a pretty bad temper. Remember that model T Ford I was telling you about? One night it wouldn't start when we were clear out among the hills where they had been working. And the car wouldn't start. And he was so mad, he told my mother, bring me the axe. And she went over, she thought he wanted to make a hole underneath the car or something, so she went and got the axe and he took it from her and was starting to beat the car up with it. And she took it away from him. No, no. She'd break the car. How are we going to get home? So he had a bad temper, and he was funny. My children always remember how funny Grandpa was. He was always making faces and always aggravating my mother because he acted young. He played with the kids. And he really enjoyed the children. And my mother was always too businesslike. She just couldn't tolerate. If a kid would make a mark on the wall, she would really get uptight, you know, like riding on the wall like the kids do and crayons. She would really get aggravated, but my dad didn't. He thought that was cute. And that's the way I am. I think it's really cute that the kids leave their handprints on the mirror and all that.

Angela Luckey: Do they still live nearby, or where do they live?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, my oldest brother died when he was about 56 years old. He died of cancer of the liver. But he had been in the service, and he had worked quite a bit. His name was Jose Miguel. He used to call himself Joseph Mitchell. But he had kind of a colorful life. When he was 20, he enlisted in the Air Force. And then just a little bit before the war, he went AWOL. And we were always told not to say where he was, although we knew where he was. And we knew that he had changed his name. So he used to write to us all the time and let us know where he was. But since he deserted before the war, you know, they didn't really make too much out of it. I imagine they looked for him, but he was in a town in Idaho named Council when we were living in Nyssa. So one day we went and picked him up and took him to Nyssa with us. And then when we came to Pocatello, he enlisted in the service under that same name that he was using, which was Richard Madrid. And he enlisted in the service, and he went clear to India. And the war wasn't over yet, and he was in that district. Well, I can't remember what they called it, but it was in the Mid-Eastern places. And we have a picture of him there. And he used to send us pictures and lots of little things from India. But the day, oh, he'd been out a month. He'd been out of the service a month when the FBI came looking for him. And things got straightened out. There was a little bit written in the paper about it, and that was it. He put in his time anyway in the service.

So they, I guess they pardoned him. And my youngest brother, yeah, he was two years younger than myself, and that's Jose Luis. He died in an industrial accident in Boise in 1967. He already had five children. He had divorced once and married again. So he has five children that he left. And his oldest son, Luis, worked down in Florida and in California with the NASA program. And the second one lives in Fort Hall. And I don't know what he does. He was a fireman there for a while. And the third son works as a reporter and radio announcer. And right now I think he's working in construction, I'm not sure. I don't see them very often. And the other two from the second wife live in Nampa. My niece is an inhalation therapist, and she works in Payette, I believe. And the brother, I don't know what he does. I think he works for a trader company. He saws wood, kind of like a carpenter, I guess. I really don't know. But that's his family. My oldest brother never married, so he never... And then my youngest brother went to ISU, graduated as a teacher. And he taught from the first grade up, I think, up to the sixth grade, and then he went to work for the University of Utah. To tell you the truth, I don't really know what it is he did, but now he's retired and he's counseling. He's doing a lot of counseling to the... Especially the Mexican people, the Mexican students that are having a hard time in school. He helps them. And then for the longest time, he worked in that Guadalupe Center, teaching English to the people that came in from Mexico, Puerto Rico, and even Chinese and Laotian people, teaching them English. And he's had a very full life in education, and he's still enjoying it. And my sister, since she was very sickly when she was born, she has always been kind of sickly. And recently she had been quite ill. But she lived, they said she wouldn't, but she's 51 years old. So like I said, everything's been pretty good for us. Our children are all working. And I just love my grandchildren.

Angela Luckey: Do you have some customs and traditions that your ancestors had?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: I mean, cultural kinds of things? Well, whenever we have too many green chilies, we string them up in a ristra, like they did in New Mexico. My dad taught us how to do that. And you see, I have one my brother brought me. And we use a lot of chile colorado, and we eat a lot of tortillas, only we make them out of flour. We don't use the corn an awful lot. But I remember when we were younger, my mother and my dad used to make pies out of prunes and raisins. Everybody around, when I tried to make one for my children, no way do they like them. But we loved them. Of course, down in New Mexico, that's about the only fruit they could preserve during the winter. They'd dry apples and dry plums and raisins and stuff. I know they had that kind of fruit during the winter, and they made quesos from milk. And they drank a tole, which is the dried corn, and then they grind it into a fine powder, and they mix it with milk and boil it. And put cinnamon in it, and it's delicious. I tried to feed that to my kids, and they don't like it. But we did, and we won custom from New Mexico that my dad always used to do, is cook the beans with dried corn. He would soak the corn and clean the beans and put them all together in a bucket, and then dig a hole outside in the dirt, and set a fire in it, and then take out all the cinders and put the bucket of beans and cover it with a moist sack, and then put dirt over it. And all those beans would be delicious by the evening.

And if he had a little salt pork he'd put in them, those beans were so good. And of course, here, and he would cook corn that same way, corn on the cob, leave the husks on it, and build a hole, and take out the fire afterwards, and just put them in the hole and cover them up with lots of wet gunny sacks, and then put a top on it and put dirt on it. We tried that once. We burned it all. It was awful. We had bought a whole gunny sack full of corn, and we were going to do what Grandpa did with it. All the corn husks were burnt to a crisp, and the corn tasted awful. But those were cooking customs that they had. And then, of course, the Christmas holidays, when we were young, weren't celebrated anywhere near like people celebrate now. The way they used to talk, they would make plays and posadas, and they had a play that they'd make called Los Matachines. And according to the way they said, it was quite a pageant, and very colorful. They would oust Satan out of heaven and throw him to the ground, and then they would have skits that would talk about why. My dad used to remember all those lines, and he used to recite them to us. It was really fun to listen to him, but we never saw it. We never saw it when we lived in Grand Junction. Nobody did anything like that. The only thing we did that they taught us was that we'd go from house to house and say, Merry Christmas, and they would give us all kinds of goodies at each door. They'd be prepared. This was mostly the people from Colorado, because the people from Mexico didn't know that. You were like posadas? No. It might have been a splinter from

that, because, see, we'd go from house to house, but we didn't say anything other than, Merry Christmas. And the people would open the door for us, and they'd either feed us there or give us goodies to take home. I remember they used to give us little empanaditas and bunuelos and atole, if we would come in and give us atole, and candy, Christmas candy. So it was fun for us then. However, it didn't last very long because we got too big and we didn't do that anymore. But it was kind of like trick or treat here. But, oh, they're nice memories, you know. And another thing that my parents did a lot, it was done in Grand Junction a lot, was to have velodrios. And they would rig up an altar in the corner of the room. And this is where my sister's mother, when she was young, she just used to love to decorate that altar. My dad would make the altar and her dad would help, and they would put linen scarves on it and then decorate it with crepe paper. And then they would bring all their images that they had, you know, their statues of the Virgin Mary and all the others. Lots of them had different ones, big ones and little ones, and from the neighborhood they'd bring all their statues. And then they would spend the night, the evening and the night, praying the rosary and singing alavados, they called them. I just used to love to hear them. And then they would take a break and then they'd come back and say another rosary and more songs.

And then at midnight we'd feed the people, and there was always chile and, what else did they feed them? Oh, beef, roast, I guess, roast beef, and chile colorado and tortillas and buñuelos. And lots of the people would get together and bring in food. And the one thing we never had was tamales or enchiladas because we didn't know anything about them, you know. The people from Colorado at that time didn't have that influence from Mexico, I guess. Mostly because we never got along. The people from Mexico didn't like the people from Colorado and New Mexico at that time. Didn't get along at all. So I remember that, and then at midnight everybody would go home after they'd eaten. And it was always really nice. I really enjoyed it. I was just a kid, you know, and I really enjoyed that. I really liked to hear the singing. And lots of people knew those songs. I never heard them in church. These velodios, were they for a week? A week? Yeah. Did they get a person? No, no. They were just celebrating the saints, celebrating the fact that they were kind of, Catholic, I guess. I don't know. That was a very old-fashioned tradition because after I was about, well, when we came to Oregon, I was 17, like I said. They hadn't had them for a couple of years or so then. Maybe five years. Nobody had them anymore. When did they have them? Oh, along the time when I was about seven, eight, nine, ten. But I mean, what time of the year? Was it any season? I don't remember that. I don't remember if it was anything probably. Well, All Saints Day is in October, isn't it? November. November. November. Maybe it was then. I don't remember. I've never heard of that before. Yeah, and like I said, they made those probably once a year. The community of the people that were from Colorado, you know, the manitos, they would come from all over to come to those advientos.

Angela Luckey: So religion was pretty important in your family?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, I imagine so. They made us go to church and dotrina and all that. Yeah, my dad, well, being that they were raised out in the farms, out in the ranches, away from the churches, they didn't get mass but once a month. And so I think they were kind of used to that. Because my mother and my dad, I don't remember. They attended church in the holidays. And whenever we had what they called a mision, they would send a priest that spoke Spanish. And we'd have the whole church to ourselves. And they'd even teach us Spanish hymns. And I really liked that. I really enjoyed it. I learned a lot more of the Catholic religion during those times than I did in English. For when I was young, you know. And of course we always went to catechism. And my brother, Jose Miguel, went to a parochial school until he was about 15.

But I never got to go because we were too poor. By that time they couldn't afford to send me and my brother Louis. So that's when we went to the local public schools, yeah. But religion did play quite a bit. My mother used to say her novena pretty often. La novena del Santo Nino. And her, oh, and I can remember when we lived out in that farm, my brother's padrino of baptism, he was an old sheep herder. And he'd come to stay with us in the winters. And he would have us. Every night we kneeled and prayed the rosary and said the stations of the cross no matter what. And me and my brother Louis would be. And my dad would go like that. There we are. And my mother had a rug on that front room where we all kneeled that was made out of straw. It was real pretty, but oh, that was hard on the knees. It was so hard we'd get up and we had all these ridges on our knees. And his name was Sanovio. And he had us praying and praying and praying and we'd get so sleepy. It was just me and my little brother. My oldest brother prayed only if he felt like it half of the time he was goofing off. But me and Louis had to sit, kneel and pray right next to my dad. And if we looked like we were even going to whisper to each other, he'd have us. But when he came, and he was there every winter. Every winter. Until we moved up town. He left my dad a big book called La Historia Sagrada. And he had taken some deer skin and put a cover to it. And just until this spring when my brother Robert was here, I gave it to him. It's been here all along. And well, my little brother was born in 1926, so we've had it since then. So I took it to him. I thought he might like to read it, but I doubt it. Maybe I'll just ask him for it back. Because it's our own move. Yeah, it is.

Angela Luckey: So tell me a little bit about what you did to socialize at Pass Your Free Time.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Oh, when we were little, we used to go to the different farms where they would celebrate birthdays. And they'd give Las Mananitas as a serenade. And we'd go. My dad would borrow the wagon from his employer. It was a huge, about as big as this, maybe bigger, as the table. And my mother would put blankets and pillows in it. And my dad and her would ride in the seat, you know, those seats that bounce up and down. And they'd hitch two horses to it. And me and my brother would be laying in the back looking at the stars. Oh, it was nice. And they'd take us to the next house. They'd pick up neighbors. And there was this one lady, her name was Seva Estiana, La Selya, and her husband, Zon Pancho. And he played the guitar, and she sang beautifully. You could hear that woman singing all over the whole valley, I think.

And to sing Las Mananitas in that beautiful voice, that just used to fascinate me. And her husband had a great big old white mustache. It was huge. And he would pay the guitar like this. He'd put the guitar up like this, and he'd play. And she'd sing, oh, I just love to hear them. We must have been about eight, nine, oh no, not even that old yet. Six, what I, six years old, five. And she was the one that made tamales. And that's how we got acquainted with tamales, although my mother never made them, never made them. So in our teenage years when we lived in town, we didn't eat tamales. But that lady was the one that made them. And she'd make sweet tamales with raisins in them. Oh, they were delicious. And this one time we went to celebrate somebody's birthday that lived in a town called Loma. And we stayed there, I think, three days. Oh, that was fun. The ladies made cakes, they made, what's that called? With the bread and the raisins. Capitota. Oh, that was good. And they made all kinds of meat, all kinds of vegetables.

And one of the daughters, which was younger, made beautiful cakes with chocolate frosting. Oh, we had never had such a wonderful time. And we, like I said, we stayed there three days. They had a violin and a guitar, and they danced until the wee hours of the morning. Everything was so nice, you know, there weren't any discrepancies in anything. Really, everybody. And some of the people were from Mexico because when we lived in the farm, I told you across the road from us, these people that came from Mexico lived there, and we got acquainted with them. And my mom and dad got acquainted with them, and they used to have these fiestas in their house. And eventually, when my little brother was born, they baptized him and had the great big fiesta for that. And I remember that's the first time I had ever eaten pineapple. And I guess since they came from Mexico, they were used to having that type of fruit. I had never seen it. You see, I was born in 24, Robert was born in 30. That meant I was four years old.

That's when he was baptized. I was just four, and my brother was two. And they had, for dessert, they had pineapple in little plates. Oh, I thought that was the most delicious stuff I had ever eaten. They didn't fix it up in any way, just out of the can. And that was just wonderful. Oh, we had eaten all kinds of canned fruit. My dad and my mother used to, you know, since they were more or less ate more gringo style than Mexican. We ate beans and potatoes and macaroni, like I told you. We ate a lot of macaroni and meat, chicken. My mother always made chicken soup and stuff like that. But when it came to making... If mama cooked anything that looked for her and we didn't like it, because we were so used to eating, oh, she made pudding, what they call natias. She used to make a lot of that, tapioca. And so we never got used to eating tamales. As a matter of fact, the sweet ones, I remember we ate when that lady used to make them. And when we moved to Grand Junction, we didn't cook like that either, because the neighborhood didn't. Everybody was from New Mexico or from Colorado. But my little sister's mother married a man from Mexico. And that's when we started to eat sopadillaros and enchiladas. And that was it, I guess, because I don't remember eating caperotada until much, much later. And I don't know if my mother already knew how to make it and never had, or if she learned to make it. But it was really good. And then another thing my dad used to make was bunuelos. He used to make those huge bunuelos and then make a sauce out of water, sugar. I think he burnt the sugar and then put raisins in it and cinnamon. And then he put the bunuelos in there and it would soak up all that. Oh, that was good. I made some a few years back when I worked for Head Start, and everybody liked it. I haven't made any since then. That reminds me.

Angela Luckey: Go in and make some now. Tell me about your singing.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Oh, well, when I was about, well like I said, I always enjoyed singing, and this lady, I think, was an incentive to me. Because I can remember I used to pick up every little tune that I would hear and I could sing it. My dad and my mother used to think that was really strange because they thought I was really smart because I could pick up all kinds of tunes like that from different people. This lady used to sing, Las Mananaitas del Rey Davil, and I could sing that tune. And of course, like I said, I was only about four around that time. Well, anyway, I think that she was sort of an incentive for me because I loved music. And my mother and dad had an old phonograph and they had an old Bing Crosby record or somebody that sang Bye Bye Blackbird. And I knew it. I couldn't read, but I knew exactly where that record was all the time. I could bring it out and play it. And then when we moved into town, of course, like I said, there was always people that played a guitar. Anywhere you looked, there was somebody that played a guitar. Anyway, I was already about twelve when these people lived across the alley from us, right there in the same little community where we lived. And he played a saxophone and the guitar and a banjo. And I just used to love the hearing. Well, anyway, I started to learn how to play the guitar with my old Lydia Mendoza records.

And I messed around with the little guitar my dad bought me until I learned how to make it sound like it did in the record. So I thought I invented it, you know. Anyway, I could sing El Noviero the way she played it. And I sang, oh, we had, that's one I remember the most. And I could make it sound just like she did. And then of course when they did Las Mananitas, I could play that on the guitar too, chord it, you know. And so I went on to experimenting with my fingers and watching people. This man used to come and he just used to love to sing. Any occasion he would sing, he'd bring his guitar. So I learned a lot from him. I used to really watch him. And then there was the little house dances and parties that they'd have people play guitars and sang mostly. And so I learned how to sing a toto nilco from this man and he showed me how to use my fingers and the chords. And so then this man that lived across the alley, they used to ask him to go play at different dances, house dances, you know.

And so he needed somebody to play the guitar so he asked me. Of course I thought I was really neat. I was about thirteen or so. And he used to teach me with his feet he'd keep the time so I could keep the time with the guitar. And he played the saxophone and other men played the violin and other men played, sometimes we had a mandolin and sometimes an accordion I think. I'm not sure, but I was the only one that played the guitar so I had to really keep that beat going. And he'd teach me, he'd play his saxophone and beat with his feet on the floor and I could keep up with him pretty good. So I did that quite a big pay us two dollars a night each when we went. And I played at several dances and lots of times we used to make our own out in El Patio. We'd put water on the ground and we'd sweep it up and it would get hard. And boy you should see the dances we'd held outside. We were about fourteen, fifteen years old. By that time everybody in the neighborhood knew how to play the guitar and sing. There was a couple of girls farther away from us that used to just sing beautifully and they played the guitar too. So while we'd play, two of us would play and the others would dance and then two others would come and play and we could go and dance. It was really funny. We had a lot of fun and then sometimes even the Italian people that lived around the sides there would come out and listen to us play.

Angela Luckey: This was in Pocatello?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: No, no, no, in Grand Junction. Because I didn't come to Pocatello until I was eighteen. At that time we used to gather and play and sing. There was my sister's cousins, of course she was a tiny baby, but those cousins that would come in from New Mexico and from, I can't remember, San Luis. And we'd have so much fun just singing and playing the guitars. And that was our teenage hangout at the time, just outside. And I remember my dad and my mother used to let me have all kinds of kids over at the house while there were some of the other girls, which were only about two other girls that lived in the neighborhood. Their dads wouldn't let them invite boys over. But since I played the guitar and I was such a tomboy, I had all kinds of boys at my house and we'd all have really good time just dancing and singing. Just like this one girl used to say, she was from another community they called La Colonia. They were mostly people from Mexico and she used to say. They were jealous of us. And then, like I said, I played for them. And then when we came to Pocatello, I think we had been invited to a birthday dinner to the sasuetas. And then from there we went to a dance, because they invited us to go to a dance.

And that's where they asked me to sing in that dance. And I didn't know anybody but the sasuetas. And of course Mike played the guitar, and so he's the one that said we would sing. And so I can't remember what it was I sang, but... And everybody thought I was Indian, you know. And they wondered how come Indian sang in Spanish. That's when they decided I wasn't Indian, I guess. But it was really funny because the expression on people's faces, you know, it seemed like they, you know, it seemed like it was strange to see a girl singing and playing the guitar, I guess. I don't know. It just made me feel kind of timid about it, you know. And anyway, that was the same dance where I met Manuel, my husband-to-be. But he was 19 and I was 18. And I never got to see him again until we were in our twenties, because that very next day he went into the service. And I think I got to see him once during that time. He came home on furlough over to the garcias. And I was gone to New Mexico at that time because my dad and I went right around the spring of 1944, I think we went to New Mexico. That's when I told you where he showed me the little place where he had been born and raised called Chaparito. The houses were all lined in caradas, like they say, with red dirt. And it made all the houses look pink. And the trees outside were in bloom and they were pink. They had pink flowers. Oh, it was pretty. I really, really liked that. And he showed me where all the little stores were and where he was young. And anyway, at that dance here in Pocatello is where I met Manuel. And we got married six years later. So we didn't hardly ever see each other before that.

Angela Luckey: How was your wedding?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, it was a typical Mexican wedding. And we had a big fiesta. Got married in the church. And we didn't have a honeymoon because he worked. And I think I was working then, too. I was working in that little restaurant. And it was a little Chinese restaurant right there on south, on center, west center. And then this girlfriend of mine that worked in the same restaurant, her name was Julia. And she and her husband were moving out from the apartment up above the little restaurant. And so she let me and Manuel have that apartment and they moved to a house. And so we lived there for a while. And I worked. Well, I think I worked for about a month after we got married. And then we moved. But it was a typical Mexican wedding. Did it go all day? All day and all night? Yeah, we had a big dance over here at the Black People. We had a USO building over here on Pocatello Avenue. And that's where the Mexican people used to hold their dances. And yeah, dances. And so we had a big dance there. But it was like I said, all day people ate and drank. All night people danced and drank.

Angela Luckey: Did you have all of that party at that USO place?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: No. Did you have it at home? We had the food at home. We lived on North 4th, the house up there where it isn't there anymore. But my dad and my mother and some of Mama's friends helped her cook. And I don't remember what the food was, but they had lots of it. Lots of people would come in and coming in and out. And then at night we had the dance. What did you wear? I wore a typical veil and long dress, white dress. Was it satin? Yeah, satin. And my maid of honor had a beautiful yellow dress, long, long dress. Did you choose colors? No. We had thought that if she could buy a blue dress, but we went over here, we tried all the stores, and we couldn't find anything that she liked or fit her well enough. So she was real dark. Her name was Rosita Bernal. She's married now. She lives in Louisiana somewhere. She and I went to this Linc School of Business together. She was able to fit this beautiful yellow dress that fit her just beautifully. So that's what she wore. And it was gorgeous, and I was thinking about that dress the other day. I don't remember who I gave it to.

Angela Luckey: What did Manuel wear?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Oh, he wore a nice suit. We have a picture in there that if you want to see it, you want to see it right now or later. He wore a suit, and Felix wore a suit. It was all really nice. We didn't have a mask. We just had an afternoon wedding. And there was lots of people who went. Well, all our friends, which were lots of them at that time, all the marillos, all the yzalgozos. I can remember. The girls gave me a shower before I got married. My friends married. I don't remember if Dolores wasn't here. She had already gotten married and lived in California. But it was really typical Mexican wedding.

Well, I shouldn't say typical because down in Grand Junction, when people got married, they went from the place where they ate to the place where they were going to hold the dance, and they played a march. The violin and the guitar first, and then the wedding couple, and then the matron of honor in the back, and then all the people that were eating there would come. And everybody would be all dressed up, and they would go into the place where they usually held the wedding dances. That's why I remember just the one where my sister's uncle got married. And they held the dance in my house because we had a big front room. And they came with the violin and guitar playing the march, but I don't remember what it was. Anyway, they would all come in, and the bride and groom would dance, and then the rest of the people would come in and dance. That was really neat.

Angela Luckey: So you made like a little procession?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Yeah, a little procession. But ours wasn't that way because we were more modern already by that time. And besides that, it was about five blocks up. In those days, there was a lot of spirit of nationalism. Yeah, yeah. There was. And the people, another thing that they did back in Colorado was la entrega de los novios. The father, la entregava, la novia, al novio, il reguel papa del novio, the father of the groom would sing the entrega to the father of the bride. And that was made of honor in one of those. I can't remember any of the words nor the tune, but he would sing this offering, offering his daughter to their family. And then the groom's father would accept the offering of their family to theirs and offer their family so that they would all become a united family. It was really pretty, but I cannot remember it.

Angela Luckey: So the father had to be good singers?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Oh, yeah. They were. They were. I remember my girlfriend got married when she was 15 and I was her maid of honor, and that's how they did it. And they did the same thing. They had the dinner at her house and then the dance at my house because my house was, they had the bigger front room and so everybody could dance there. But it was really neat. Like I say, I never did learn the entrega. That sounds interesting.

Angela Luckey: One last thing I would like you to tell us a little bit about the organization that was here for the Mexican.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Oh, what was it? The organization of Latin American Spanish-speaking friends, I think it was. Oh, Spanish American-speaking people. That's what it was. And it was the organization of it. Latin American-Spanish speaking people. That's what it was. And it was the organization of it. Frank Rodriguez, Mike Huerta, I believe, and Mike Rivera, Arnulfo. What's his name? Juanita's husband's name? Arnulfo. No. Madri. No, no, no, no, no. Juanita's husband? Yeah, Juanita Arnulfo Alvarez. And let me see, and there was myself and Mary Marillo. Well, she was Samaro at that time, I believe. And Julia, Frank's wife, and Juanita Alvarez, and I think Daisy and Guero were in it. Sanchez, Sam and Isabelle, and Penagos. Well, they weren't Penagos yet. Did Bill be loved? Oh, Edgar and Olga, Penagos. And I can't remember Tony Rojas's family. And I can't remember. Oh, Mike Huerta's brother, Johnny, and Vicki Huerta.

Angela Luckey: Arnulfo.

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Yeah, Juanita Arnulfo Alvarez. And let me see, and there was myself and Mary Marillo. Well, she was Samaro at that time, I believe. And Julia, Frank's wife, and Juanita Alvarez, and I think Daisy and Guero were in it. Sanchez, Sam and Isabelle, and Penagos. Well, they weren't Penagos yet. Did Bill be loved? Oh, Edgar and Olga, Penagos. And I can't remember Tony Rojas's family. And I can't remember. Oh, Mike Huerta's brother, Johnny, and Vicki Huerta.

Angela Luckey: What was the purpose of this organization?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, actually, we got together so that we could be a united Mexican community, a Spanish-speaking community anyway. And our goals were to be united and have our own place and gather up money. We had thought about a scholarship for ISU and a social club, mostly social, because we didn't have too many social things here in Pocatello. And we celebrated the holidays in the 16th of September and the 5th of May. And, well, it kind of geared mostly toward a social club. And we held lots of neat things there. It was really a wonderful thing. And I think we lasted six years. It was really nice, though, when we did have it. Actually, we wanted to make it bigger and, like I said, have our own scholarship for ISU. That was our biggest goal. And to be able to help our kids get jobs. Even the teenagers had their own little --

It was called Latins, and Lewis and Ramona, and all the Rodriguez girls. Oh, it was cute. I don't know what they did much, but right around that time, though, it was, I think they lasted a year right around that time and just kind of started falling apart, all of it. And we didn't put on programs or anything like that except on the 16th of September and the 5th of May. We'd organize all the little kids to sing, the Mexican anthem. And Tony and Johnny and somebody else made a skit one time. Oh, it was the funniest thing you ever didn't see. Tony played this drunken old lady he had on a dress and a hat. I really don't remember, but at the time it was so funny. And the dialogue was really funny. Do you ever remember that cartoon that used to come out in La Prensa, Don Cacabuate, and Don Ceferino, and I don't know. I remember that we could have used, you know, if we had stuck with it. I was one of the die hards. I was one of the last ones that gave up.

Angela Luckey: Do you want to tell me what happened to it?

Victoria Archuleta Sierra: Well, I think that Mexican people don't organize very well because of a lot of reasons. Some could be, oh, I hate to say jealousy, but there's a lot of discord. For several different reasons. Some people pull this way, some people pull the other, and it's actually never united for a long time, for any length of time. I don't know, we're all too, probably too eager, and then there are the people that are lackadaisical about it, and some are kind of think that we can't do anything anyway, so why try it? So a lot of people hang back until it's going good, and then they'll come in. But I don't know, we really thought we had it together when we had that, and then it just started falling apart. But just people, just not getting along together, and not liking other people's ideas, and people not liking other people's background, and prejudice. That's why I say it could have been a really good thing, and it could have still been going now, but for these little nitpicking things that happen, and after that everything else that the kids had started hasn't lasted long.