Moving Forward While Looking Back

World War II, Japan, and the University of Idaho

Contents: About the Exhibit | World War II and Japanese Incarceration | The End of the War and Japan's Reconstruction | Tech

About the Exhibit

December 7, 1941 the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor thus pulling the United States into World War II. Entering the war had drastic and unforeseen consequences on many living in the country. Not only were many people now preparing for war, but a sector of the population saw their rights infringed upon and were forced to relocate from their homes. Deemed a potential threat to the security of the United States, Italian and German immigrants, as well as those of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast were forcefully relocated to incarceration and internment camps further inland, two of which were located in Idaho. Though Italian and German immigrants were also targeted, those of Japanese ancestry, including many American citizens, faced forced removal in larger numbers.

This initial act of war not only had a direct impact on those of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast, but would lead to the use of the atomic bomb on two Japanese cities, ultimately ending the war with Japan. After the war those who were forced from their homes in the United States had to readjust to life, many had lost their homes and possessions do to their incarceration and were concerned about returning home. Those hurt by the atomic bomb in Japan also had to rebuild and move on from the atrocities of war.

This exhibit explores the impact that World War II had not only on those of Japanese ancestry in the United States, but also those in Japan who survived and rebuilt after the use of the atomic bomb and the role Idaho played through it all. It looks at the atrocities of war and the resilience and hope of those who live through it.

The exhibit was put together by Courtney Berge, Archives and Exhibits Assistant in Special Collections & Archives. The creation of the exhibit was prompted by the University’s receipt of roof tiles from Hiroshima University. In researching for the exhibit, Berge could not ignore the materials she found regarding the treatment of those of Japanese descent in Idaho and the University during World War II. She broadened the initial scope of this exhibit to include Japanese forced removal and the University of Idaho’s policy regarding Japanese students during the war.

World War II and Japanese Incarceration

Executive Order 9066

After some investigation, it had been reported to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in November 1941 that the majority of those with Japanese ancestry along the West Coast were loyal to the United States. Even with this report on February 19, 1942 President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order allowed military commanders to exclude civilians from military zones, and ultimately resulted in the creation of “relocation” centers for those of Japanese descent, both foreign born (Issei) and American citizens (Nisei).1

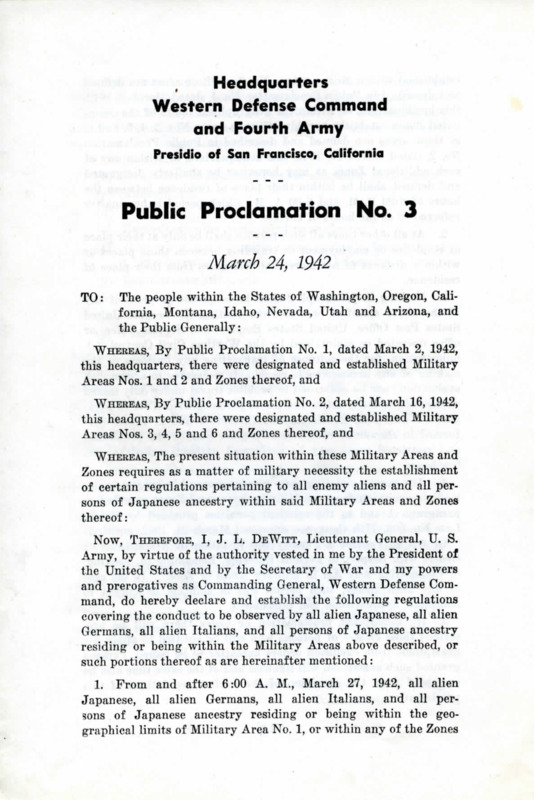

Executive Order 9066 was followed by several public proclamations made by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command. The first two proclamations established six military areas along the West Coast. The third established a curfew for German and Italian immigrants, as well as anyone of Japanese ancestry. DeWitt then encouraged the voluntary evacuation of those with Japanese ancestry along the West Coast. This encouraged evacuation was soon followed, on March 29, 1942 by Public Proclamation No. 4, which began the forced removal of those who were of Japanese descent.2

Japanese Relocation to Idaho

Approximately 120,000 Issei and Nisei were affected by the forced relocation set into action by General DeWitt. Those forced to relocate were ordered to report to temporary detention centers, called assembly centers. There were 15 of these centers total spread throughout Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona. Operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) these temporary detention centers were located on fairgrounds, horse tracks, and other makeshift facilities. While living in the detention centers, evacuees often faced food shortages and unsanitary conditions. For months, evacuees lived in these conditions until more permanent detention centers, called relocation centers, were finished being constructed further inland. These more permanent camps began receiving evacuees in May 1942, with the final transfer to relocation centers occurring in October 1942. 3

Minidoka

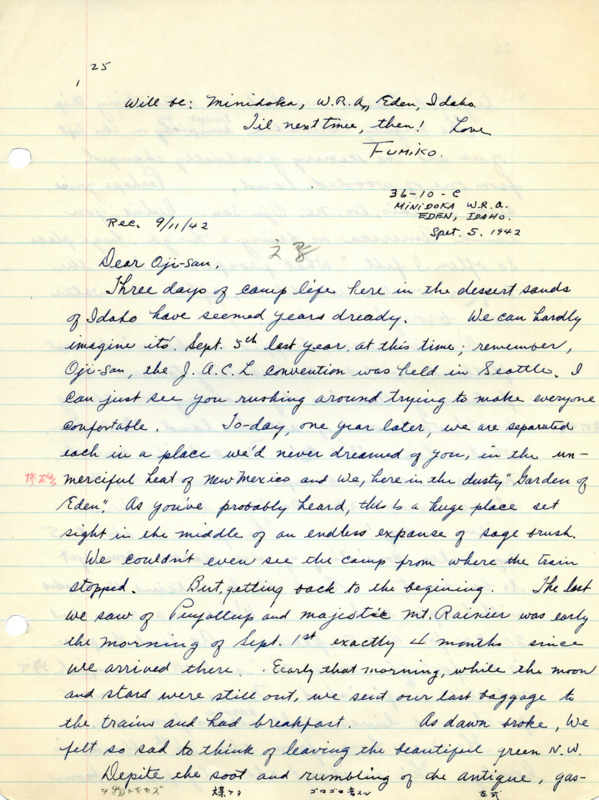

Idaho was home to one WRA relocation center in southern Idaho, near Hunt. The Minidoka War Relocation Center extended over 33,000 acres with 900 of those acres used to house, at it’s peak approximately 9400 individuals incarcerated there. The remaining land was used either for administrative work or agriculture. 4

When the first incarcerees arrived at Minidoka in August 1942, the construction of the camp was not finished, there was no running water and a sewage system had not been installed. Those who arrived were discouraged and unhappy with their living conditions. Families faced cramped living quarters with it being common for a family of 8 or 9 people living in a one bedroom apartment. Beyond that, the camp was situated in a high-desert climate. The majority of the incarcerees were from the Pacific Northwest and were not prepared for the harsh winters and summers of southern Idaho. Even with these conditions, incarcerees worked to improve the camp conditions by planting trees, flowers, and shrubs to beautify the camp, as well as keeping gardens for fresh produce.

The camp closed in October 1945 and the land was later offered for homesteading to veterans. Today, much of the former site is occupied by farmhouses and irrigated fields, but in 2001 72-acres of the site was established as the Minidoka National Historic Site. It’s purpose today is to educate the public about the experiences of incarcerees to ensure a similar experience doesn’t happen again.5

Kooskia

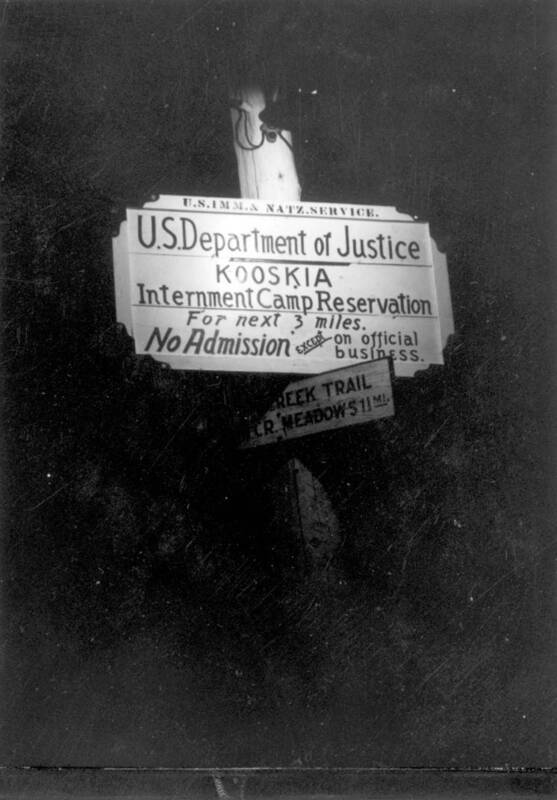

While the WRA operated several incarceration camps throughout the country, the Immigration and Nationalization Service (INS) operated several internment camps, including one near Kooskia, Idaho. Unlike the the incarceration camps, these internment camps were used to detain “enemy aliens.” These “enemy aliens” had been identified as potentially dangerous to national security, though many of the individuals were detained with little evidence to suggest they posed a threat to the United States.6

The Kooskia Internment Camp was located at the confluence of Canyon Creek and the Lochsa River in northern Idaho. Detainees at the camp were made up of volunteers from other detention camps and most worked construction on a portion of the Lewis and Clark Highway between Lewiston, Idaho and Missoula, Montana. The Kooskia Camp operated from May 1943 to May 1945 and saw 265 Japanese internees make their way through.7 Learn more about the Kooskia Interment Camp from our Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook digital collection.

Japanese Students and the University of Idaho

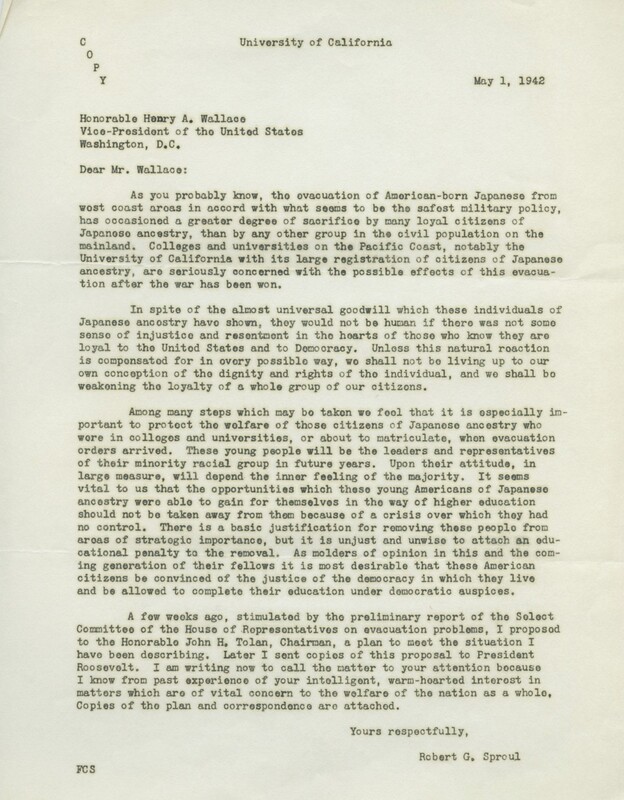

In March 1942, a month after Executive Order 9066 was enacted, and as Lieutenant General Dewitt began releasing public proclamations limiting the rights of the Issei and Nisei in militarized zones, students and educators alike questioned whether Nisei students would be able to finish their education. Several universities within the militarized zones had a large number of Nisei students. Both Lee Paul Sieg, president of the University of Washington, and Robert Gordon Sproul, president of the University of California, Berkley, spoke out against the forced removal of students and worked to find ways to allow students to finish their studies 8

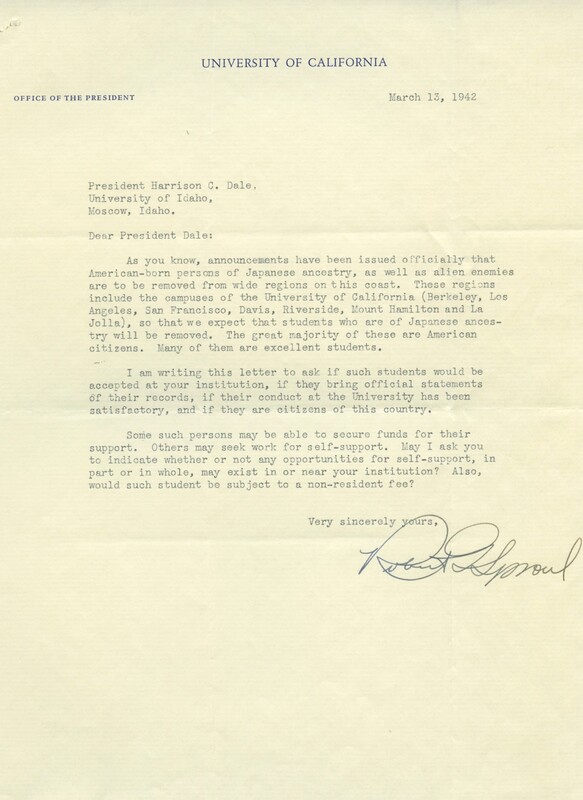

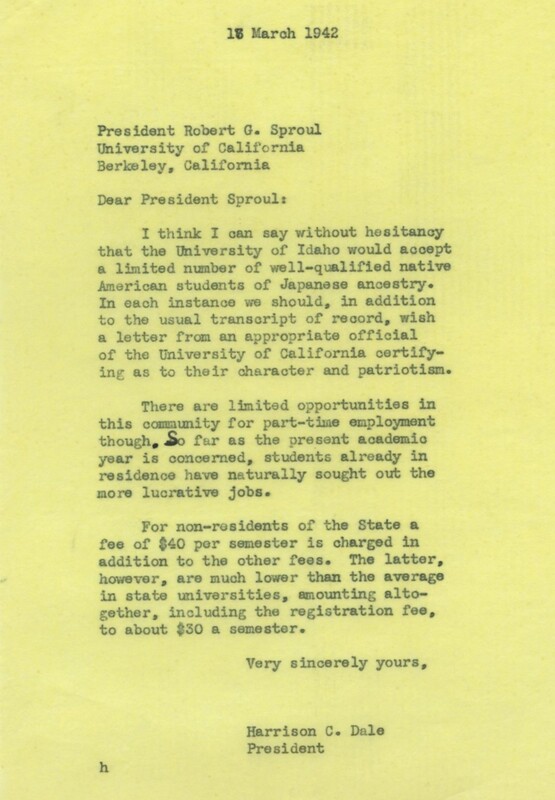

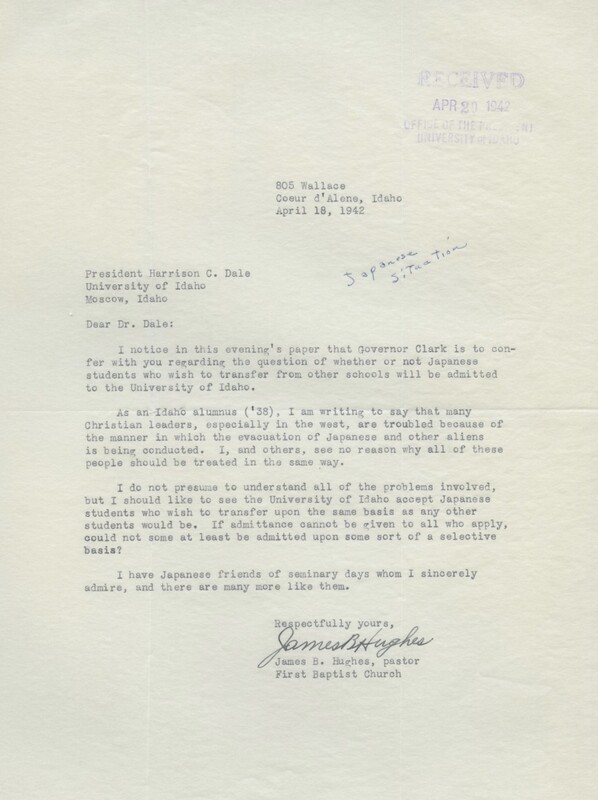

Sieg and Sproul, along with other educators, students, and churchgoers along the West Coast held a conference in March 1942 to discuss the issue and began efforts to coordinate student relocation. In March, 1942, Sproul sent letters to several universities further inland inquiring to their willingness to accept Nisei students from the University of California. The University of Idaho received one of these letters and President Harrison C. Dale responded that they would gladly accept a “limited number of well-qualified native American students of Japanese ancestry.” They would be required to pay out-of-state fees and he couldn’t guarantee them work in town, but foresaw no issues.

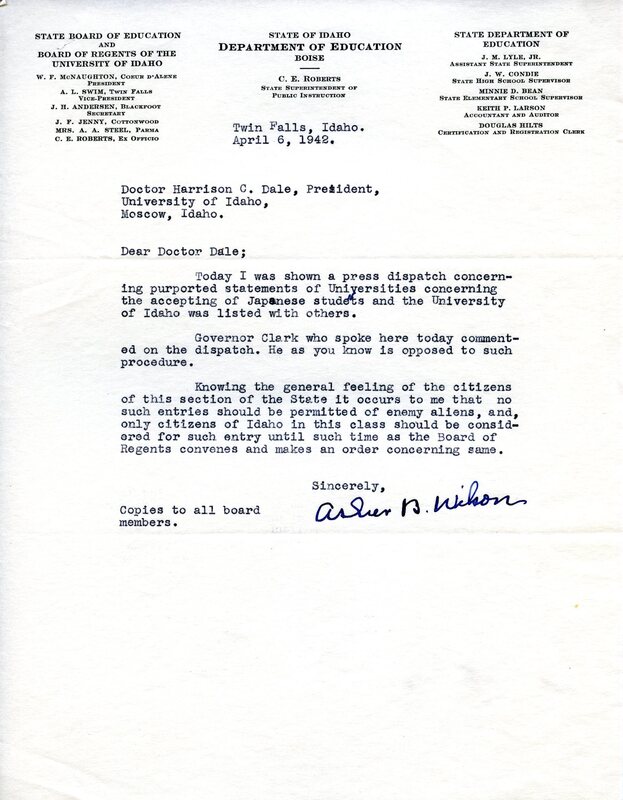

A few days after President Dale sent this response, a newspaper reported that the University of Idaho would accept non-resident Japanese Americans and waive tuition for them. This false report brought President Dale under much scrutiny. The State Board of Education quickly responded to Dale stating that the State Board and Governor Chase A. Clark were opposed to permitting “enemy aliens” to come and study in Idaho.

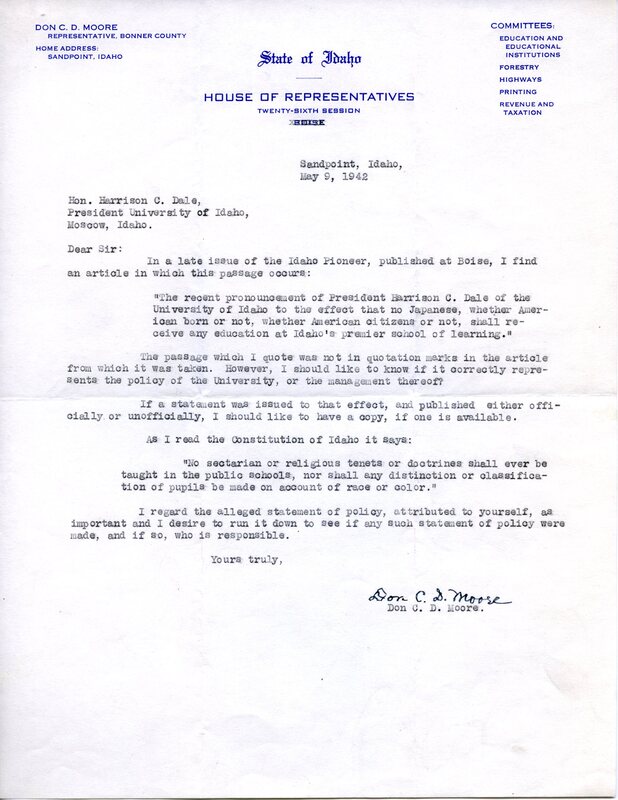

Due to the controversy that arose from the newspaper’s false claims and the censure from the governor and State Board of Education, President Dale contacted President Sproul rescinding his previous agreement. The University of Idaho would only accept Japanese students if they were Idaho residents and had graduated from an Idaho high school. Later the State Board would vote on this making it official. This, however, did not come without it’s own controversies. Residents of Moscow, and Idaho were opposed to these actions and were concerned with the treatment of these American citizens. President Dale received letters from local clergy, organizations, and government concerned with the decision and the impact it would have on Japanese students.

The End of the War and Japan’s Reconstruction

The Atomic Bomb and End of the War

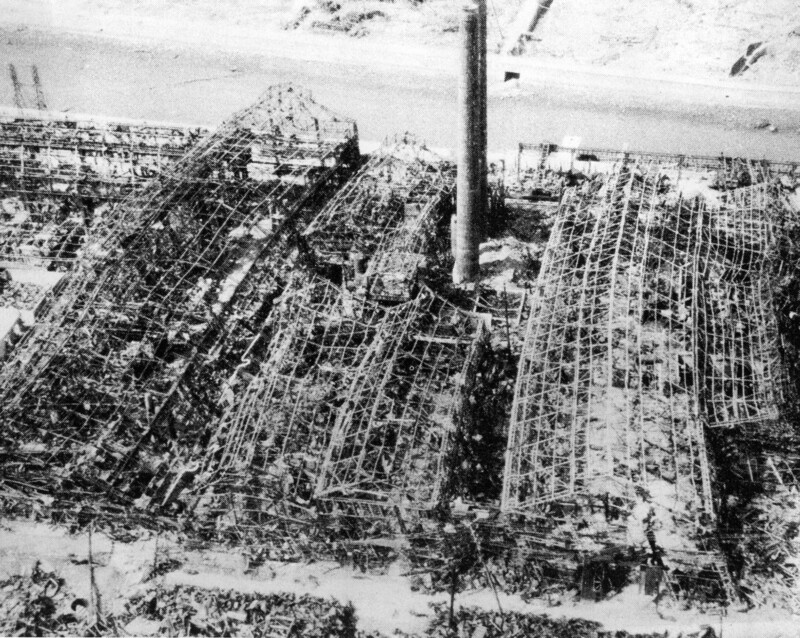

On July 26, 1945 after nearly 3 years of war with Japan, President Harry S. Truman and the other leaders of the Allied forces gave a final warning to Japan in the Potsdam Declaration, calling for unconditional surrender or Japan would face “prompt and utter destruction.”9 When Japan had not surrendered a week later the United States took action. On August 6, 1945 the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. With an estimated population of 280,000 people, the initial explosion killed approximately 80,000 in a matter of minutes, leveling the city.10 Three days later, the United States made another attack, this time on Nagasaki, where approximately 75,000 people died immediately. In the following months, the two cities saw between 95,000 and 171,000 more deaths due to the bomb. The city of Hiroshima estimates that nearly 240,000 people were ultimately killed by the bombing of their city, either directly or indirectly.11 On August 14, Japan accepted the terms set forth in the Potsdam Declaration, officially signing the instrument of surrender on September 2, 1945, ending the war with Japan.12

A Hope for Peace

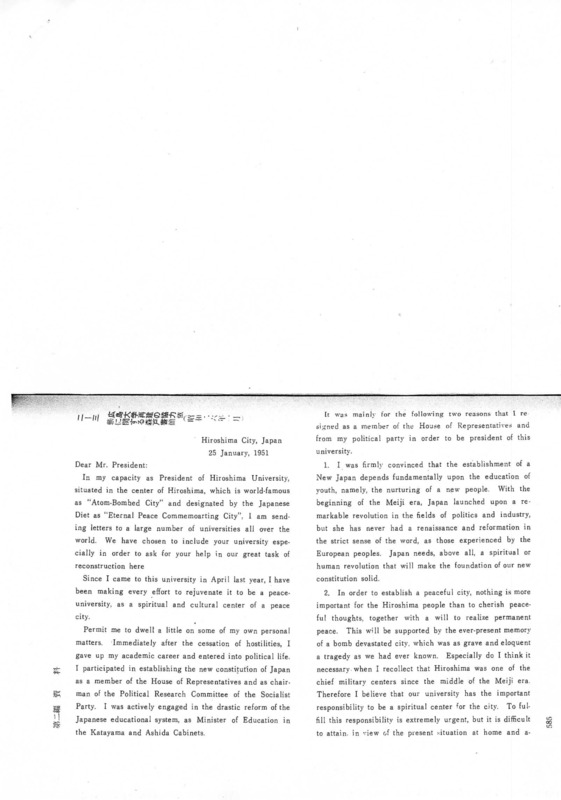

Years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the University of Idaho received a letter from the president of Hiroshima University, Tatsuo Morito. In his letter, he described the city of Hiroshima’s desire to be designated an “Eternal Peace Commemoarting[sic] City” and he asked the university to help during their reconstruction.

Morito requested two things from the university, a book to be added to their library and a tree to be planted on the university’s campus. The book was requested to help build the university’s library because all it’s contents had been lost in the bombing, and the tree was requested because Hiroshima University existed in that moment as “standing on bare, desolate ground destitute of a single tree with green leaves.” Morito wished to turn the campus from “…a burnt, red-rusty hue to a fresh green color. Not red, symbolizing struggle and blood-shed, but green which is the color of growth and home….”

Though, as Morito pointed out, his request would not have a large economic impact, it would “be of deep significance, from the spiritual point of view, in contributing to international understanding and the permanent peace of the world.” The University of Idaho responded to his request by sending, not only a book for Hiroshima University’s library, but also seeds to be planted on their campus. In case the seeds would not thrive in Hiroshima’s climate, the university also sent $3 for Hiroshima University to buy and plant a tree on their campus. In his letters, President Morito imparted the importance of education in the hopes for a lasting peace in the world. In the creation of a Peace Library at Hiroshima University he hoped to establish an institute for research into international peace problems, and the donations to the library would serve to “promote an atmosphere of universal friendship.”

Advocating for Peace at the University of Idaho

Even before receiving President Morito’s letter, the University of Idaho has had a similar view in how to promote peace. Now called the Borah Foundation, in 1929 the William Borah Outlawry of War Foundation was established to honor and continue the work of Idaho Senator William Borah on behalf of peace. Nearly since it’s inception, the Borah Foundation has regularly held programs to educate and advocate for peace in the world. The first program brought peace and human rights advocate Eleanor Roosevelt to campus which culminated with the planting of a tree on the university campus, one that still stands today. Over the years, the Foundation has continued to hold programs devoted to understanding the causes of war and how to establish a lasting peace through the annual Borah Symposium. This has often culminated in the planting of trees in the University of Idaho Arboretum which now make up the Borah International Peace Grove. 13

References

-

The Incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II, The Atomic Heritage Foundation, https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/incarceration-japanese-americans-during-world-war-ii. Accessed 15 September 2020. ↩

-

Japanese-American Internment During World War II, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation. Accessed 22 September 2020. ↩

-

Assembly Centers, Densho Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Assembly_centers. Accessed 19 January 2021. ↩

-

Life at Minidoka National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/miin/learn/historyculture/life-at-minidoka.htm. Accessed 19 January 2021. ↩

-

Japanese American Incarceration during World War II Friends of Minidoka, http://www.minidoka.org/history-world-war-two-internment. Accessed 27 January 2021. ↩

-

Wegars, Priscilla., et al. Imprisoned in Paradise : Japanese Internee Road Workers at the World War II Kooskia Internment Camp. Asian American Comparative Collection, University of Idaho, 2010. ↩

-

Kooskia Internment Scrapbook About the Camp, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/kooskia/about.html. Accessed 20 January 2021. ↩

-

Okihiro, Gary Y., and Ito, Leslie A. Storied Lives : Japanese American Students and World War II. University of Washington Press, 1999. ↩

-

Potsdam Declaration, Atomic Heritage Foundation, https://www.atomicheritage.org/key-documents/potsdam-declaration. Accessed 1 October 2020. ↩

-

Fact File : Hiroshima and Nagasaki, WW2 People’s War, https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/timeline/factfiles/nonflash/a6652262.shtml. Accessed 1 October 2020. ↩

-

Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - 1945, Atomic Heritage Foundation, https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/bombings-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-1945. Accessed 1 October 2020. ↩

-

Hall, M. (2013, September 02). By the Numbers: End of World War II, CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2013/09/02/world/btn-end-of-wwii/index.html. Accessed 1 October 2020 ↩

-

About the Borah Foundation, University of Idaho Borah Foundation & Symposium, https://www.uidaho.edu/class/borah/about. Accessed 22 October 2020. ↩

Technical Credits - CollectionBuilder

This digital collection is built with CollectionBuilder, an open source framework for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that is developed by faculty librarians at the University of Idaho Library following the Lib-Static methodology.

Using the CollectionBuilder-CSV template and the static website generator Jekyll, this project creates an engaging interface to explore driven by metadata.