Episode 42 : Nineteen-nineteen Item Info

In this episode, titled “Nineteen-nineteen” we hear an excerpt from “USFS1919: A Ranger, A Cook and a Hole in the Sky”, which makes up part of Norman MacLean’s best-known work: A River Runs Through It.

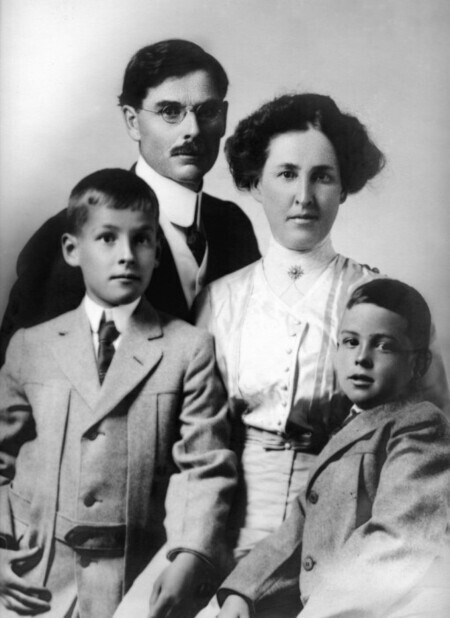

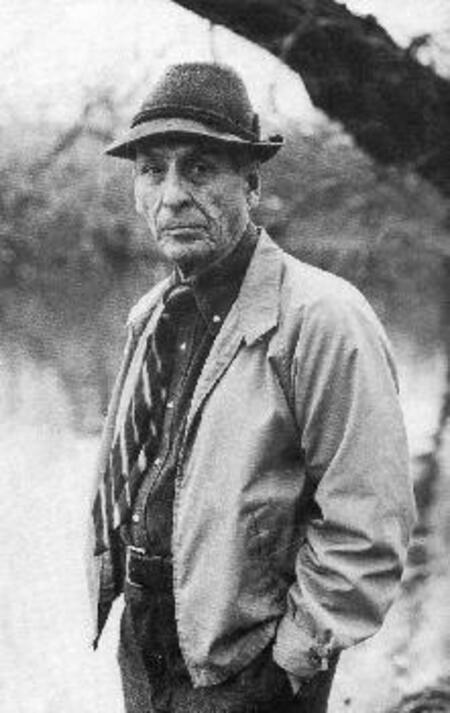

Born in Clarinda, Iowa, on December 23, 1902, Norman was the son of Clara and the Reverend John Norman Maclean, a Presbyterian minister, who managed much of the education of Norman and his brother Paul. In 1909, the family relocated to Missoula, Montana, where the landscape made a considerable impression on the young Norman. Because he was too young to enlist in the military during World War I, Norman worked in logging camps and for the United States Forest Service in what is now the Bitterroot National Forest of northwestern Montana. The novella USFS 1919: The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky is a semi-fictionalized accounts of these experiences.

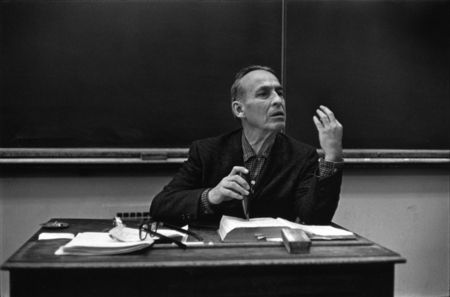

In 1931, Norman married Jessie Burns, and in 1940, he earned his doctorate from the University of Chicago where he declined a commission in Naval intelligence to serve as Dean of Students during World War II. At the University of Chicago, Maclean taught Shakespeare and the Romantic poets, and during his last decade on the Chicago faculty, Maclean held an endowed chair as William Rainey Harper Professor of English.

After his retirement in 1973, he began to write down the stories he liked to tell to his children, John and Jean. A River Runs Through It and Other Stories was published in 1976, the first work of original fiction published by the University of Chicago Press and was nominated by a selection committee to receive the Pulitzer Prize in Letters in 1977, but the full committee ignored the nomination and did not award a Pulitzer in that category for the year.

Norman Maclean died on August 2, 1990, in Chicago, at the age of 87 of natural causes.

This excerpt gives a poet’s view of the landscape now known as the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, and highlights some of the differences and similarities to the area today.

Audio Excerpt

I was young and I thought I was tough and I knew it was beautiful and I was a little bit crazy but hadn't noticed it yet. Outside the ranger station there were more mountains in all directions than I was ever to see again - oceans of mountains - and inside the station at this particular moment I was ahead in a game of cribbage with the ranger of the Elk Summit District of the Selway Forest of the United States Forest Service (USFS), which was even younger than I was and enjoyed many of the same characteristics.

It was mid-August of 1919, so I was seventeen and the Forest Service was only fourteen, since, of several possible birthdays for the Forest Service, I pick 1905, when the Forest Division of the Department of the Interior was transferred to the Department of Agriculture and named the United States Forest Service.

In 1919 it was twenty-eight miles from the Elk Summit Ranger Station of the Selway Forest to the nearest road, fourteen miles to the top of the Bitterroot Divide and fourteen straight down Blodgett Canyon to the Bitterroot Valley only a few miles from Hamilton, Montana. The fourteen miles going down were as cruel as the fourteen going up, and far more dangerous, since Blodgett Canyon was medically famous for the tick that gave Rocky Mountain Fever, with one chance out of five for recovery. The twenty-eight-mile trail from Elk Summit to the mouth of Blodgett Canyon was a Forest Service trail and therefore marked by a blaze with a notch on top; only a few other trails in the vast Elk Summit district were so marked. Otherwise, there were only game trails and old trappers' trails that gave out on open ridges and meadows with no signs of where the game or trappers had vanished. It was a world of strings of pack horses or men who walked alone - a world of hoof and foot and the rest done by hand. Nineteen nineteen across the Bitterroot Divide in northern Idaho was just before the end of most of history that had had no fourwheel drives, no bulldozers, no power saws and nothing pneumatic to take the place of jackhammers and nothing chemical or airborne to put out forest fires.

Nowadays you can scarcely be a lookout without a uniform and a college degree, but in 1919 not a man in our outfit, least of all the ranger himself, had been to college. They still picked rangers for the Forest Service by picking the toughest guy in town. Ours, Bill Bell, was the toughest in the Bitterroot Valley, and we thought he was the best ranger in the Forest Service. We were strengthened in this belief by the rumor that Bill had killed a sheepherder. We were a little disappointed that he had been acquitted of the charges, but nobody held it against him, for we all knew that being acquitted of killing a sheepherder in Montana isn't the same as being innocent.

As for a uniform, our ranger always wore his .45 and most of our regular crew also packed revolvers, including me. Bill was built to fit his hands. He was big all over. Primarily he was a horseman, and he needed an extra large horse. He was not the slender cowboy of the movies and the plains. He was a horseman of the mountains. He could swing an ax or pull a saw, run a transit and build trail, walk all day if he had to, put on climbing spurs and string number nine telephone wire, and he wasn't a bad cook. In the mountains you work to live, and in the mountains you don't care much whether your horse can run fast. Where's he going to run? Bill's horse was big and long-striding, and could walk all day over mountain trails at five miles an hour. He was a mountain horse carrying a mountain man. Bill called him Big Moose. He was brown and walked with his head thrown back as if he wore horns.

Every profession has a pinnacle to its art. In the hospital it is the brain or heart surgeon, and in the sawmill it is the sawyer who with squinting eyes makes the first major cut that turns a log into boards. In the early Forest Service, our major artist was the packer, as it usually has been in worlds where there are no roads. Packing is an art as old as the first time man moved and had an animal to help him carry his belongings. As such, it came ultimately from Asia and from there across Northern Africa and Spain and then up from Mexico and to us probably from Indian squaws. With the coming of roads, this ancient art has become almost a lost art, but in the early part of this century there were still few roads across the mountains and none across the "Bitterroot Wall." From the mouth of Blodgett Canyon, near Hamilton, Montana, to our ranger station at Elk Summit in Idaho nothing moved except on foot. When there was a big fire crew to be supplied, there could be as many as half a hundred mules and short-backed horses heaving and grunting up the narrow switchbacks and dropping extra large amounts of manure at the sharp turns. The ropes tying the animals together would jerk taut and stretch their connected necks into a straight line until they looked like dark gigantic swans circling and finally disappearing into a higher medium.

Bill was our head packer, and the Forest Service never had a better one. As head packer, [he] rode in front of the string, a study in angles. With black Stetson hat at a slant, he rode with his head turned almost backward from his body so he could watch to see if any of the packs were working loose. Later in life I was to see Egyptian bas-reliefs where the heads of men are looking one way and their bodies are going another, and so it is with good packers. After all, packing is the art of balancing packs and then seeing that they ride evenly - otherwise the animals will have saddle sores in a day or two and be out of business for all or most of the summer.

Up there in front with Bill, you could see just about anything happen. A horse might slip or get kicked out of the string and roll frightened downhill until he got tangled around a tree trunk. You might even have to shoot him, collect the saddle, and forget the rest of what was scattered over the landscape. But mostly what you were watching for took Bill's trained eye to see - a saddle that had slipped back so far the animal couldn't breathe, or a saddle that had slipped sideways. In an outfit that large, there are always a few "shad bellies" that no cinch can hang on to and quite a few "bloaters" that blow up in the morning when the cinch touches them and then slowly deflate.

The Bitterroot Divide, with its many switchbacks, granite boulders, and bog holes, brought out every weakness in a packer, his equipment, and his animals. To take a pack string of nearly half a hundred across the Bitterroot Divide was to perform a masterpiece in that now almost lost art, and in 1919 I rode with Bill Bell and saw it done.

The divide was just as beautiful as the way up. In August it was blue with June lupine. Froth dropped off the jaws of the horses and mules, and, snorting through enlarged red nostrils, the animals shook their saddles, trying without hands to rearrange their loads. Not far to the south was El Capitan, always in snow and always living up to its name. Ahead and to the west was our ranger station - and the mountains of Idaho, poems of geology stretching beyond any boundaries and seemingly even beyond the world.

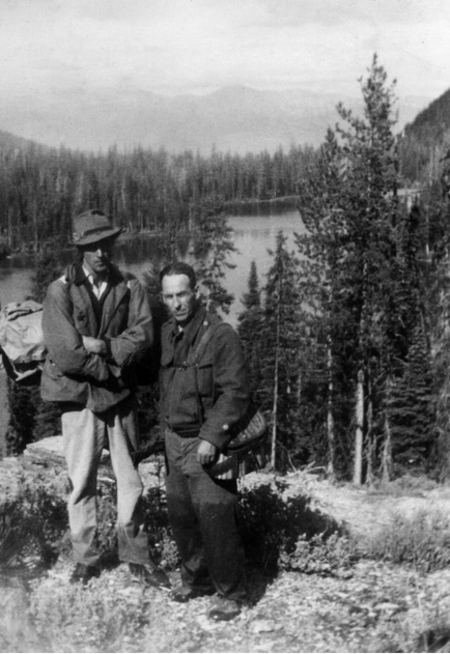

Six miles or so west of the divide is a lake, roughly two-thirds of the way between Hamilton and Elk Summit, that is the only place where there is water and enough grass to hold a big bunch of horses overnight. K. D. Swan, the fine photographer of the early Forest Service, should have been there to record the design of the divide - ascending in triangles to the sky and descending in ovals and circles to an oval meadow and an oval lake with a moose knee-deep beside lily pads. It was triangles going up and ovals coming down, and on the divide it was springtime in August.

The unpacking was just as beautiful - one wet satin back after another without saddle or saddle sore, and not a spot of white wet flesh where hair and hide had rubbed off. Perhaps one has to know something about keeping packs balanced on the backs of animals to think this beautiful, or to notice it at all, but to all those who work come moments of beauty unseen by the rest of the world.

[Once, while] working with the packs [Bill] said, "Why don't you go up on the lookout for a couple of weeks and find out [if there are rattlers up there]?"

I didn't ask him when; I knew he meant now. I lifted the two packs until I thought they were balanced, and then started for the door. He added, "If you spot any fires, call them in. And, if there's a big rain or snow, close up camp and come back to the station."

I knew it would be dark before I got to Grave Peak, so I asked the cook to make me a sandwich. I had a big blue bandanna handkerchief, and I put the sandwich in the handkerchief and tied the handkerchief to my belt in the middle of my back. I picked up my razor, toothbrush, and comb, and my favorite ax and Carborundum stone. Then I strapped on my .32-20 and started up the high trail.

It was twelve miles and all up, but I never stopped to rest or eat the sandwich. Bill seemed to be watching all the time. By walking hard I kept even with daylight until near the end. Then darkness passed over me from below - just the dazzling peak above told me where I was going.

Modern lookouts live on top of their peaks in what are called "birdcages"; - glass houses on towers with lightning rods twisted around them so that the lookouts are not afraid of lightning striking them, and for twenty-four hours a day can remain on the towers to watch for lightning to strike and smoke to appear. This, of course, is the way it should be, but in 1919 birdcages, as far as we knew, were only for birds. We watched from the open peak and lived in a tent in a basin close to the peak where usually there was a spring of water. From my camp to the lookout was a good half-hour climb, and I spent about twelve hours a day watching mountains.

Near the top there were few trees and nearly all of them had been struck by lightning. It had gone around them, like a snake of fire. But I was to discover that, on a high mountain, lightning does not seem to strike from the sky. On a high mountain, lightning seems to start somewhat below you and very close by, seemingly striking upward and outward. Once it was to knock me down, toss branches over me and leave me sick.

The basin where my tent was pitched was covered with chunks of cliff that had toppled from above. I did not see a rattlesnake, but I shared the basin with a grizzly bear who occasionally came along flipping over fallen pieces of disintegrated cliff as he looked for disproportionately small grubs. When I saw him coming, I climbed the highest rock and tried to figure out how many hundreds of grubs he had to eat for a square meal. When he saw me, he made noises in his mouth as if he were shifting his false teeth. In a thicket on top of a jack pine, I found the skeleton of a deer. Your guess is as good as mine. Mine is that the snow in the high basin was deep enough to cover the trees, and the deer was crossing the crust and broke through or was killed and eventually the snow melted. There was a tear in my tent so when it rained I could keep either my food or my bed dry, but not both.

It doesn't take much in the way of body and mind to be a lookout. It's mostly soul. It is surprising how much our souls are alike, at least in the presence of mountains. For all of us, mountains turn into images after a short time and the images turn true. Gold-tossed waves change into the purple backs of monsters, and so forth. Always something out of the moving deep, and nearly always oceanic. Never a lake, never the sky. But no matter what images I began with, when I watched long enough the mountains turned into dreams, and still do, and it works the other way around - often, waking from dreams, I know I have been in the mountains, and I know they have been moving - sometimes advancing threateningly, sometimes creeping hesitantly, sometimes receding endlessly. Both mountains and dreams.

While I was making breakfast [on my last day on the Graves Peak Lookout], I heard the ticktock of a clock repeating, "It's time to quit; it's time to quit." I heard it almost as soon as it began, and almost that soon I agreed. I said to myself, "You fought a big fire and packed a big gun," and I said, "You slit waxy sticks of dynamite and stuck detonation caps in them and jumped back to watch them sizzle," and then I said, "You helped Bill pack and you watched mountains by yourself. That's a summer's work. Get your time and quit." I said these things several times to impress them on myself. I knew, in addition, that the fire season was over; in fact, the last thing the ranger had told me was to come in if it snowed [and it had]. So I rang two longs for the ranger station; I rang two longs until I almost pulled the crank off the telephone, but in my heart I knew that the storm had probably blown twenty trees across the line between the peak and the station. Finally, I told myself to stay there until tomorrow when most of the snow would be gone and then to walk to the station and get my time and start over the hill to Hamilton.

What I neglected to tell myself is that it is almost impossible to quit a ranger who is sore because you do not like his cook, or to quit a story once you have become a character in it.

[When I got down,] Bill said, "Why do you go back with the trail crew? They've been doing without you, and I need somebody around camp to help me straighten out the stuff now that the season is over." Then he said, as if he had put the two things together in his mind, "How about a game of cribbage at the station tonight?" I said I would if he needed me and to myself I said I'd put off for a day or two telling him that I was going to quit. More and more, I sensed I was slipping out of life and being drawn into a story. I couldn't quit even when it was time to quit.

Ever since the ranger had realized that the cook was fancy with the cards and so had taken my place as his favorite, I'd felt a growing need to set a record. I wished that it could be in packing and that I could become known overnight as one of the Decker brothers, who had designed the latest packsaddle, but I couldn't live long in that pipe dream, and powder work made me sick, so it had to be walking. I knew I could outwalk anyone in our district, and at the moment I needed a little local fame, and I needed it bad.

Twenty-eight miles from Elk Summit to the mouth of Blodgett Canyon plus a few more miles to Hamilton is not outstanding distance, just as distance, but still it is a damn tough walk. For one thing, those were Forest Service miles, and, in case you aren't familiar with a "Forest Service mile," I'll give you a modern well-marked example. Our family cabin is near the Mission Glaciers and naturally one of the many nearby lakes is named Glacier Lake, which is at the end of the Kraft Creek Road, except that the final pitch is so steep you have to make it on foot. Where the trail starts there is a Forest Service sign reading: "Glacier Lake - 1 Mi." Then you climb quite a way on the trail toward Glacier Lake and you come to another Forest Service sign reading: "Glacier Lake - 1.2 Mi." So a good working definition of a "Forest Service mile" is quite a way plus a mile and two-tenths, and I was going to walk over thirty Forest Service miles to Hamilton, about half of them up until I was above mountain goats and the other half down and down until my legs would beg to start climbing again and I wouldn't be able to comply. The trail was full of granite boulders, and I would manage somehow so that Bill would hear that I had walked it in a day.

Long before daylight I was using my feet like beetle feelers to find my way across Horse Heaven Meadow. Don't look at me, look at the map, because I don't have the kind of a mind that could make up a name like that. Even if you want to drop the Horse Heaven business, you still have a high mountain meadow just before daybreak, full of snorts and spooks. There are lots of horses out there but also a lot of other big animals. Elk and deer for sure. Maybe bear. They wake in darkness and come down from the hills to drink, and then slowly feed toward higher ground until it gets hot and is time for them to lie down again. A clank in the darkness is the scariest of all sounds, but you know a second afterwards it has to be a hobbled horse. If you are listening for dainty sounds to signify deer, there is nothing daintier than a snort - but there are deer there. They snort, and then bound. Elk snort, and then crash. Bear bolt straight uphill in a landslide - no animal has such pistons for hindquarters.

I still walked in wonderland after daylight. Far ahead on gray cliffs I could see the white specks that were not spots in my eyes. The trail was already getting steep and I knew before noon I would be higher than the mountain goats and from experience I knew that there is nothing much higher on earth.

When I finally made the divide, I carefully studied the center of it, traced in my mind what I designated as the state line between Idaho and Montana and then made a small section of it real by pissing on it - a very short dehydrated state line. I always did this on big divides, especially on the Continental Divide where one is left wondering whether he is going to drain into the Atlantic or the Pacific. The divide here is not the Continental Divide, but it stirs the imagination.

Then I sat down and rested above the white goats. I looked back where I had worked three summers, and it looked strange. When you look back at where you have been, it often seems as if you have never been there or even as if there were no such place. Of the peaks in the sky, my old lookout, Grave Peak, of course, was the one I knew best. When I lived on it, it was a hard climb out of a basin full of big rocks and small grubs, a tent with a finally-mended hole, trees decapitated by lightning, no soft place to sit and one grizzly and one rattlesnake. But here from the divide, it was another reality. It was sculpture in the sky, devoid of any detail of life. There is a peak near my home town we call Squaw's Teat. It is not a great mountain but it has the right name for Grave Peak when viewed from the distance of the divide. From the divide the mountain I had lived on was bronze sculpture. It was all shape with nothing on it, just nothing. It was just color and shape and sky. It was as if some Indian beauty before falling asleep forever had decided to leave exposed what she thought was not quite her most beautiful part. So perhaps at a certain perspective what we leave behind is often wonderland, always different from what it was and generally more beautiful.

Gallery

- Title:

- Episode 42 : Nineteen-nineteen

- Date Created (ISO Standard):

- 2013-08-09

- Description:

- In this episode, titled "Nineteen-nineteen" we hear an excerpt from "USFS1919: A Ranger, A Cook and a Hole in the Sky", which makes up part of Norman MacLean's best-known work: A River Runs Through It. Born in Clarinda, Iowa, on December 23, 1902, Norman was the son of Clara and the Reverend John Norman Maclean, a Presbyterian minister, who managed much of the education of Norman and his brother Paul. In 1909, the family relocated to Missoula, Montana, where the landscape made a considerable impression on the young Norman. Because he was too young to enlist in the military during World War I, Norman worked in logging camps and for the United States Forest Service in what is now the Bitterroot National Forest of northwestern Montana. The novella USFS 1919: The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky is a semi-fictionalized accounts of these experiences. In 1931, Norman married Jessie Burns, and in 1940, he earned his doctorate from the University of Chicago where he declined a commission in Naval intelligence to serve as Dean of Students during World War II. At the University of Chicago, Maclean taught Shakespeare and the Romantic poets, and during his last decade on the Chicago faculty, Maclean held an endowed chair as William Rainey Harper Professor of English. After his retirement in 1973, he began to write down the stories he liked to tell to his children, John and Jean. A River Runs Through It and Other Stories was published in 1976, the first work of original fiction published by the University of Chicago Press and was nominated by a selection committee to receive the Pulitzer Prize in Letters in 1977, but the full committee ignored the nomination and did not award a Pulitzer in that category for the year. Norman Maclean died on August 2, 1990, in Chicago, at the age of 87 of natural causes. This excerpt gives a poet's view of the landscape now known as the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, and highlights some of the differences and similarities to the area today.

- Duration:

- 22:07

- Subjects:

- authors fiction forest service members

- Section:

- Wilderness Voices

- Location:

- Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (Idaho and Mont.)

- Publisher:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Source:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Original URL:

- https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/2013/08/09/nineteen-nineteen/

- Source Identifier:

- Selway-Podcast-ep42

- Type:

- Sound

- Format:

- audio/mp3

- Language:

- eng

- Preferred Citation:

- "Episode 42 : Nineteen-nineteen", The Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/sbw/items/sbw321.html

- Rights:

- Copyright: The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project. In Copyright - Educational Use Permitted. For more information, please contact University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives Department at libspec@uidaho.edu.

- Standardized Rights:

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/