Episode 43 : Ancient Communities of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Item Info

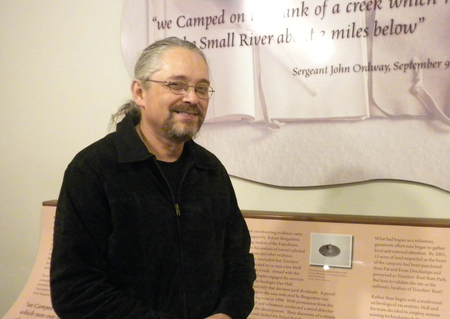

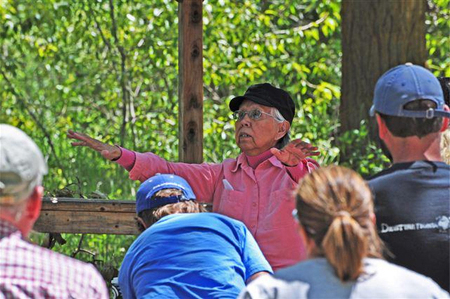

In this episode, titled “Ancient Communities of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness,” we hear from Vernon Carroll, whose job it is to interpret history for visitors to the Bitterroot Valley at Traveler’s Rest. From showcasing a museum dedicated to Lewis and Clark, to cultivating interest in the Native tradition of educational storytelling, Vern brings the past of this important area to life.

Vernon Carroll, a member of the Blackfeet Tribe, was born in Cut Bank, Montana, and worked as a cattle rancher there alongside his father, maintaining a lifelong interest in the history and culture of the native peoples who lived in Montana. His ranch itself boasted three buffalo jumps and numerous tipi rings, among other native sites and artifacts. His love of history led him to work for a year as the interim manager of the Glacier County Museum in Cut Bank. In 2002, he retired from ranching when he was hired as the pioneer Interpretative Specialist at the Traveler’s Rest State Park in Lolo, Montana.

Audio Excerpt

Interviewee: Vernon Carroll

Interviewer: Debbie Lee

Location: Traveler's Rest, Lolo, Montana

Date: October 29, 2012

VC: So that's also what sets us apart in a sense as far as the Lewis and Clark story. But again that's just, you know, such really such a small part of the history here but it's what, you know, it's what has got, it's what's given us the opportunity to talk about those other stories.

DL: Yah. So how do you, what are some of the, I mean there's one sort of revisionary history, wait, I mean there's like the, you know, the master narrative where they came out and conquered the land and explored and discovered and then there's the revisionary history where Lewis and Clark brought the wave of White settlers that then, you know, put Native Peoples on reservations and killed them and chased them to Canada and stuff, that massacred. So are there some other nuance ways of looking at that meeting of these different kinds of people, people from the East or of European ancestry with people who have been camping and living and working and harvesting here, you know, forever?

VC: Uh-huh. I think the one thing that probably strikes me the most about the particular part of the story that is represented, at least in part here in the Bitterroot Valley, is the need or the reliance that the Corps had on the Native People. The fact that they were treated well. The fact that they were in many ways welcomed, not understood, and I'm absolutely certain that particularly in the encounter here with the Salish up the river here a bit that there was a lot of skepticism and it would have been just about as easy to say, you know, this is a problem, you know, and we don't need to deal with this or.

DL: You mean on the part of the Salish or?

VC: Uh-huh.

DL: Okay, yah.

VC: Yah, yah. In a sense I think that's, and there are stories within the Salish tradition that it was a, they had the opportunity or they did consider at least not helping and possibly even, you know, eliminating. So there were decisions made. I think that was particularly important. I do think that also that, this is kind of getting back to the master narrative and I don't think we want to get away too much farther from that part in a sense that realizing that there was a, you know, they were carrying the banner of manifest destiny. It was, it was, this country was destined to be coast to coast and realizing that the moment they crossed the Bitterroot or they crossed the Continental Divide they were in a foreign territory. This land was claimed primarily by the British and yet, you know, they were, you know, the term, they proceeded on. They continued and knowing full well or believing full well that this country was destined to control and they really began a process. I think that one thing that's really, really interesting about the Lewis, is they attempted to, you know, designate or, they tried to figure out who the people were and then categorize them, not fully understand how complex, you know, the Native social structures were and, you know, wanting very much in a very kind of linear European way is to put people in boxes. And only follow that that basically from their experience in the East it was going to be a lot easier when the time came to create reservations or move people. We wanted to know that and, you know, they were essentially the first ones to kind of begin that process which continued and continued and continued, you know, right through the establishment of reservations and, you know, their failure to really understand the complexity of. And I think that, as far as implications that's one of the most significant ones. And, yah, it was the beginning of opening up the West and, you know, the missionaries followed soon after the trappers and traders, the agriculture, the railroad, those things happened soon but, you know, Lewis and Clark in many ways kind of established that template for how this country was going to really deal with Native People and, you know, it has struck me that how little they understood and the assumptions they made and the assumptions themselves became part of the National narrative and National policy. So it was a really, really significant part of that too.

DL: Uh-huh. So what were some of the assumptions that kind of are important to you?

VC: Well, I think going back to this idea of trying to categorize people and establish some kind of order and when you don't really have the skills or you know the understanding of the people to do that I think inevitably you're going to mess it up and I think, you know, throughout the whole Expedition Lewis and/or Clark or whoever else made references to specific tribal groups and in many ways that sort of became the, you know, how we continue to associate. We label the people in some ways kind of based on what, you know, they, and I don't know the story particularly well but even the understanding of who the people were here and, you know, Flathead was a term that kind of came out of that and we all wonder where that comes from. They had very creative use of some Native, of Salish language to describe the area which Salish people now kind of scratch their head and say that's not even a word, we don't even know what that means but yet it became, you know, it became part of through their journals and through their maps, you know, how when we start writing things down they tend to become, yah.

DL: So their journals and words and maps went back East and, you know, over the Atlantic and then people read those and when they came out they had those because I've read Thompson's journals and he actually not too long after Lewis and Clark is referring to Lewis and Clark saying oh, now I see what they were.

VC: Yah, exactly.

DL: What they saw but if they wouldn't have had that they might have seen something very different.

VC: They would have seen something different or interpreted it differently.

DL: Yes.

VC: So I think, you know, that that's I think one of the things that's probably to me one of the most interesting and yet kind of one of the most troubling things about that was, you know, was that particular part and how they interpreted what they saw. And then we can just sort of add on the consequences of that. You know, from that point forward that was kind of the beginning. So, yah, that was, that's one thing that was always, is interesting to me and I've been doing a little research on some of the folks over along the Columbia River and how they essentially did the same thing and how that became again sort of the road map for Government policy at that point. Assumptions that Lewis and Clark made people just kind of carried forward. And, you know.

DL: Like what, they were friendly or they are warrior?

VC: Or a part of it was even just assuming because of where people were located, assuming that, assuming a much greater relationship between those peoples because of, you know, when you encounter a couple of groups in a certain area your assumption might be maybe this is sort of, you know, based on their experience in the eastern part of this country was that these people must be related. Linguistically there may be some similarities but you're not recognizing that things were probably a lot more complicated.

DL: Uh-huh.

VC: There's a, you know, even issues, legal issues with regards to treaty rights that tend to pop up all the time in how people were kind of arbitrarily thrown together. The Flathead Reservation here in Montana is a great example. We have the Salish, the Kootenai, and the Pend Oreille. People who lived in the same area but through the wisdom of Isaac Stevens he kind of tossed them all together without really considering how that was going to work and it was particularly devastating to the Salish people because they were asked to leave the Bitterroot Valley and to move to an area that they had had some association with and live with people they'd had some association with but it wasn't home and so I think we, you know, kind of see those kinds of things that, you know. I can see, you can almost see the seeds of that in the Lewis and Clark Expedition how that all came to pass.

DL: Uh-huh. Do you know much about how the different, the Salish and the Nez Perce or the Nimipoo used the Bitterroots themselves, the mountains?

VC: Uh-huh. Well, I think to me and I don't know probably enough about it to speak with much authority but at least my experience and my understanding was that as far as sort of a traditional homeland and, you know, I realize that tribes are very mobile but the Bitterroot, at least this part of the Bitterroot Valley, probably represented more of the homeland to the Salish people. It was an area that was utilized to travel through by the Nez Perce and other tribes too. So I think within the context of the Bitterroot Valley, at least this portion of the valley. I think the relationship, the home relationship was probably, you know, that was how the Salish thought of it. Of course, it was an area where, you know, again we have all this travel and trade and it's, I think it's really, really hard to separate, well, I guess, it's hard to, you know, I guess this kind of goes back to a tendency we like to do when we study things is we like to sort of compartmentalize activities like these are social activities and these are hunting activities and these are ceremonial activities. And I think within the Native culture those weren't separated. So, again the how, well again I think there was a significance, a lot of social mixing here. I think the Salish and the Nez Perce in particular had a lot of kinship ties that were a part of this particular place. I think the traveling through, there's significant evidence that the Salish and the Nez Perce traveled together to hunt the bison and that again represented, it wasn't this neat little hunting thing, it was much more than that. So I think that, but my understanding and I may not be right about this is that the valley itself kind of represented as the traditional homeland of the Salish but yet again it was utilized and appreciated by the Nez Perce and some other tribes too.

Gallery

- Title:

- Episode 43 : Ancient Communities of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness

- Date Created (ISO Standard):

- 2013-08-13

- Description:

- In this episode, titled "Ancient Communities of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness," we hear from Vernon Carroll, whose job it is to interpret history for visitors to the Bitterroot Valley at Traveler's Rest. From showcasing a museum dedicated to Lewis and Clark, to cultivating interest in the Native tradition of educational storytelling, Vern brings the past of this important area to life. Vernon Carroll, a member of the Blackfeet Tribe, was born in Cut Bank, Montana, and worked as a cattle rancher there alongside his father, maintaining a lifelong interest in the history and culture of the native peoples who lived in Montana. His ranch itself boasted three buffalo jumps and numerous tipi rings, among other native sites and artifacts. His love of history led him to work for a year as the interim manager of the Glacier County Museum in Cut Bank. In 2002, he retired from ranching when he was hired as the pioneer Interpretative Specialist at the Traveler's Rest State Park in Lolo, Montana.

- Duration:

- 15:00

- Subjects:

- community lewis and clark nimiipuu tribe blackfeet tribe

- Section:

- Wilderness Voices

- Location:

- Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (Idaho and Mont.)

- Publisher:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Source:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Original URL:

- https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/2013/08/13/ancient-communities-of-the-selway-bitterroot-wilderness/

- Source Identifier:

- Selway-Podcast-ep43

- Type:

- Sound

- Format:

- audio/mp3

- Language:

- eng

- Preferred Citation:

- "Episode 43 : Ancient Communities of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness", The Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/sbw/items/sbw320.html

- Rights:

- Copyright: The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project. In Copyright - Educational Use Permitted. For more information, please contact University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives Department at libspec@uidaho.edu.

- Standardized Rights:

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/