Episode 38 : Impact Item Info

In this episode, titled “Impact,” we hear from Emil Keck, who had an enormous impact on the policies and people of wilderness in the Selway-Bitterroot area.

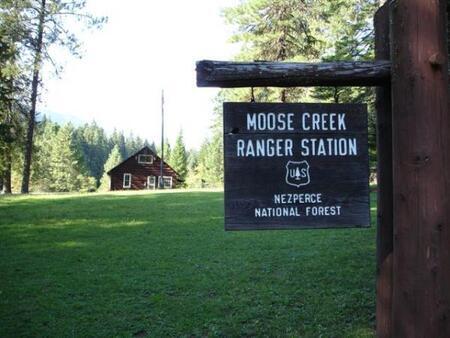

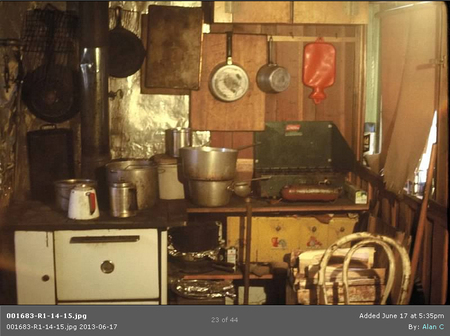

Emil Keck worked as a Forest Service employee beginning in 1962. He was in charge of construction and maintenance of some 400 miles of trails, a half-dozen suspension bridges, another dozen span bridges, the small collection of buildings around the district, and the four remaining fire lookout towers on the 550,000-plus acres that comprise the Moose Creek district in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness.

Emil, the oldest of nine children born to Russian immigrants, spent his first seven years in a sod hut in North Dakota. He began work as a logger and - before his future wife Penny was hired - had strongly objected to having women employees on the district. Following their marriage, Emil and Penny began living at the Moose Creek Ranger Station year-round. When Emil was forced to retire in 1979, Penny became the paid employee, and he stayed on as a volunteer. They continued to live and work at Moose Creek until 1988, when Emil was asked to leave. He died shortly afterward in 1990.

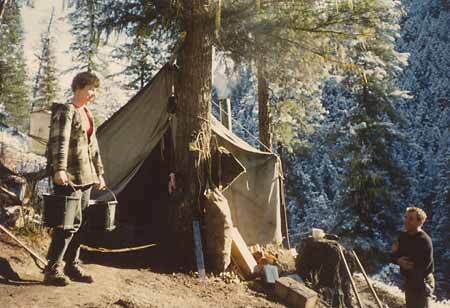

This excerpt is taken from an interview conducted by Don Biddison on November 4, 1988. Emil discusses the work he did in re-wilding the Selway-Bitterroot area in the early years of wilderness, and the work he and Penny undertook to educate campers, hunters, hikers, outfitters and rafters in care and maintenance of the beautiful natural resource by packing out garbage, not creating shortcuts that cause erosion in trails and using ideas that would eventually lead to “Leave No Trace” education in wilderness use.

Audio Clip

Interviewer: Don Biddison

Interviewee: Emil Keck

Location: Lolo, Idaho

Date: November 4, 1988

DB: Well, let's back up and take it chronologically. You went to work at Moose Creek in '62 if my recollection is correct.

EK: No, I was down here in '62.

DB: You were down here.

EK: I was at Fenn.

DB: When did you go to work at Moose Creek?

EK: Well, I went to work at Moose Creek the following year.

DB: In '63.

EK: Yeah. You see, Milo wasn't there. I was up there in the office at Fenn, and the telephone rang. I remember the number 9 rang, and it was Hess on the other end, up there at Moose Creek.

DB: It was John Hossick?

EK: Hess. His boss. Hossick was boss. Hossick was his foreman, was the ranger. Hess was an alternate ranger, a fire control officer. He said, I'm going to leave here. I said, what's the matter with you? Well, he said, my wife's gonna have a child, or had a child or something and he said I've got a chance to go over to Elk City and be a fire control officer over there. Because they sell timber year-round and I didn't think it'd be very good to be in here, you know. In Moose Creek. So that's fine. He said, Hossick wants you to come up here. He said he thinks the sun rises and sets for you. I said that's a bunch of baloney, but anyway, why would you want to leave a beautiful district like that? Then he said, he told me, so I says there's nothing to that. And then this room over here, that's Blake. Clyde Blake Junior. I had tangled with old Clyde Blake Senior on a pickup deal over at the Cedars, and so I wasn't very happy with the name Blake at all. I wasn't taking any crap from him either. So, I knocked at the door, and Blake says Come in, and he said what can I do for you? I said hey, listen I'm going to go to Moose Creek. He said, you are? When? I said just as quick as I can get the hell out of here. He said when are you coming back? I said never. Milo told me, see, I'll tell you one thing. When Milo came here, he told me, or I came to see Milo, he told me, he said this country is overrun with junk. There's junk laying from stem to stern. And the Moose Creek District is the worst of all of them.

DB: Are you talking about Number 9 phone wire?

EK: Oh, I'm talking about camp outfits and garbage and everything. All of it, you know, all of the shuckers that they had. They had piles of junk all over hell.

DB: This the outfitters or Forest Service or?

EK: Everything! Don, when you got right down to it, you couldn't draw the line. And that's why I say the study that you're making here; I don't know which was good buildings or not, because all Milo told me was clean the son of a bitch up. That's all. He didn't give a damn whose junk it was. He didn't want it around. He wanted it to get the hell out of here. And so, that's what I did. I got into real, real trouble with the crew, because I was burning up the old cabins. But Milo said don't you save one of them. As a matter of fact, you know the shack down at Three Links? And I was dragging my feet...

DB: The trappers cabin?

EK: Yeah.

DB: the trappers cabin or the old guard station?

EK: The old guard station and the trapper's cabin.

DB: There were two of them.

EK: There were three.

DB: Three of them?

EK: Yeah. See, I was up there and I looked at the tower on the south side, and the cable had gone down through the top cabin; there was a top cabin you know.

DB: On Three Links Bridge.

EK: On Three Links Bridge. And so I climbed up there and it was buried in there about that far. When they built it, they didn't. The plans called for a plate here and the plate up here on top of the cabin, but they didn't do that they just had an old 8 x 10 It was buried. They had a snag broke down off the lower side and hit that and drove her down. I knew we were going to have to have that, So I drug my feet I'm not coming. And then Milo finally sent word on, he so he said tell Keck that if he hasn't got guts enough to burn that cabin up, God dammit, he said, I'll do it. Well, I wouldn't want the supervisor to tell me that! Especially when he wanted it cleaned up! But, I didn't want to impeach on anybody either, so I went down and burned the son of a bitch up, but that was the reason that I held back on that holding, the whole establishment there. And the corral over here, there was a hay barn. And the river went down that way, and behind that was another barn they kept the stock in. They kept the saddle horse and an old shorty, the one that they had in there for pulling stuff around in, you know, in the woods. They had it in there. And this was a big thing, right here. This was right here, and here was this thing up here and on the other side of the river was another shack. So, Don, I don't know what was good shacks and what was not. I don't know how much help I can be with... Now, look, you can crucify me, because I... Milo told me to clean the son of a bitch up, period. And so I didn't pay any attention to the quality or anything about it.

DB: The only important thing now is just getting in the record that there was a cabin here, and this is what it was used for.

EK: Yeah, but I don't know for sure what it was used for. Don, I destroyed an awful lot of stuff. I don't even know what the hell it was for. But I know the stuff was out there. And there was tin cans laying around and I was told to clean her up. And that was all there was to it. So, when you got one supervisor, you and Rayfield and Sanderson and one right after the other. I wouldn't impeach on the other supervisor and you wouldn't do it either. You would say hey, now, don't you think that you could do away with the chainsaw and kind of do that by hand, and I'd agree with them, you know. But I also had a lot wider and broader assignments from the guy that got me the job to start with, and that was Milo. So, that was the reason. That was the reason. She was cleaned up, and I didn't pay any attention to who owned what. See, on the way up here, starting right out here at Fenn, you end up there, you didn't go half a mile past, see what the hell is the name of that creek? There was a cabin up in there and we burnt that Goddamn thing up, and I know... I don't know.

DB: It wasn't just in the wilderness that a cabin was burned. They were burned all over the forest.

EK: All over the forest, yeah. That's true.

DB: So it wasn't a wilderness issue. I mean I don't think the cabins were removed because they were in the wilderness; they were removed because they were...

EK: Unattractive nuisances. Here's the thing. People don't respect the Forest Service and they don't respect themselves, because they brought a lot of crap in here. And then they went and hunted, and threw the cans over the side and went back out and left it there. And what we wanted to do was just to pick it all up. Clean the thing up and get it, hell, moving out. And we had a hell of a time. A hell of a time. And Rayfield was up there and he said, you know I get the feeling that it's pretty glum around here. And you know, that poor bastard, he thought that we should make stations all the way up and down the Goddamn river and have the guys dump that stuff there. Why, that's crazy, because what you're doing is, you're leading people into a sin. They're not supposed to do that. They're not supposed to treat that beautiful land that way. They're supposed to come in, have a good time, and take the crap out.

DB: Well, which kind of leads us around to the subject of the Light Impact Camping.

EK: Yeah.

DB: Tell me about that. Its origin on the District and so forth.

EK: Oh, well, as far as I know, it started in Moose Creek. The old lady and I were responsible for it, because we were cleaning up too many outfitters' camps and so we decided that the best thing to do would be to organize our own crew. And get them on our side. And that was where she started Low Impact Camping. Right there.

DB: Now it's spread all the way across the United States, I guess.

EK: Of course it is! It is! Wait until you see Low Impact Camping... you have to do it.

Gallery

- Title:

- Episode 38 : Impact

- Date Created (ISO Standard):

- 2013-07-18

- Description:

- In this episode, titled "Impact," we hear from Emil Keck, who had an enormous impact on the policies and people of wilderness in the Selway-Bitterroot area. Emil Keck worked as a Forest Service employee beginning in 1962. He was in charge of construction and maintenance of some 400 miles of trails, a half-dozen suspension bridges, another dozen span bridges, the small collection of buildings around the district, and the four remaining fire lookout towers on the 550,000-plus acres that comprise the Moose Creek district in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. Emil, the oldest of nine children born to Russian immigrants, spent his first seven years in a sod hut in North Dakota. He began work as a logger and - before his future wife Penny was hired - had strongly objected to having women employees on the district. Following their marriage, Emil and Penny began living at the Moose Creek Ranger Station year-round. When Emil was forced to retire in 1979, Penny became the paid employee, and he stayed on as a volunteer. They continued to live and work at Moose Creek until 1988, when Emil was asked to leave. He died shortly afterward in 1990. This excerpt is taken from an interview conducted by Don Biddison on November 4, 1988. Emil discusses the work he did in re-wilding the Selway-Bitterroot area in the early years of wilderness, and the work he and Penny undertook to educate campers, hunters, hikers, outfitters and rafters in care and maintenance of the beautiful natural resource by packing out garbage, not creating shortcuts that cause erosion in trails and using ideas that would eventually lead to "Leave No Trace" education in wilderness use.

- Duration:

- 13:07

- Subjects:

- community forest service members women rangers

- Section:

- Wilderness Voices

- Location:

- Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (Idaho and Mont.)

- Publisher:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Source:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Original URL:

- https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/2013/07/18/impact/

- Source Identifier:

- Selway-Podcast-ep38

- Type:

- Sound

- Format:

- audio/mp3

- Language:

- eng

- Preferred Citation:

- "Episode 38 : Impact", The Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/sbw/items/sbw325.html

- Rights:

- Copyright: The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project. In Copyright - Educational Use Permitted. For more information, please contact University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives Department at libspec@uidaho.edu.

- Standardized Rights:

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/