ORIGINAL FOREWORD

by Sam Schrager

"There's a story out there the likes of which has never been told."

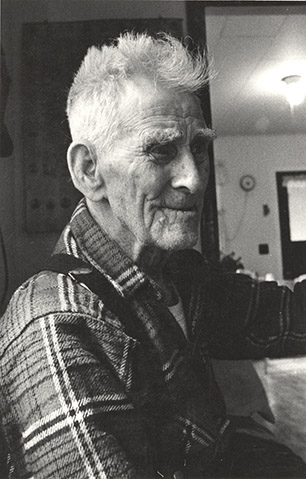

With these words Glen Gilder proposed the recording of life histories of local men and women. In the course of wide reading of Western history and fiction he had been surprised by the absence of information about the kind of life he has personally known. He decided that the exploits of cowboys, outlaws, mountain men and territorial politicians have received plenty of attention, while the experiences and values important to communities such as his have yet to be documented.

Like many young people in the inland Northwest at the turn of the century, Glen grew up on a subsistence farmstead in a pioneer neighborhood and then struggled patiently for decades to develop his own farm. Often needing to work away from home to make a living, he became well acquainted with farm families, lumberjacks, sawmillers, townspeople and miners. When I first met Glen, as a newcomer asking ill-informed questions about Idaho history, he was troubled by the passing of lifelong friends who had intimate knowledge of the varied traditions of these groups. One spring evening he took me to see Emmett Utt, a retired sawmiller who regaled us with tales of citizen retaliation against high-handed practices of the Potlatch Lumber Company. I was mesmerized by the quality of both men’s recollections and by the perfect understanding that seemed to pass between them.

That was my first glimpse of the importance of oral history within communities. I soon realized that the elders of Latah County take great pleasure in telling stories that they draw from long lifetimes of work and residence in the area. Their narratives enfold personal, family and community experiences in an unbroken continuity that extends from the frontier conditions of their childhoods to the recent transformations of their neighborhoods and towns. Their sense of history is sharpened by the newness of the country, for many of their parents were homesteaders, and they know that they had a unique opportunity to witness the formative period of early settlement and change.

Through the medium of oral history they express not only their personal knowledge of past events, but also the central beliefs of their culture. For today, with their parents’ generation gone, they have become the keepers of traditional values, who, by retelling the deeds of the old and the dead, try to link those who are younger to the community’s heritage. Many share Glen Gilder’s uneasiness that the wisdom of their culture will soon disappear. They are well aware that there has been a disruption in the transmission of traditional attitudes to future generations. They see that the world of their children and grandchildren is so different from their own that their understanding can easily seem irrelevant to the present.

For Glen, Emmett and their acquaintances, the exchange of oral history occurs often, whenever they swap stories about the past. These occasions, which can be termed storytelling events1 , are the natural context for the expression of oral history in most communities. The storytelling event is a distinct form of human communication that takes place when two (or more) people assume the roles of story-teller and story-listener. The teller narrates stories; the listener responds to them. Each participant is expected to follow local customs of social interaction, and as the event progresses each interprets and influences the other’s presentation through a process of continuous feedback. When a narrator relates oral history, he communicates his worldview through stories that are designed to interest and entertain his listeners; they respond with signs of comprehension and encouragement, and probably take turns at telling stories themselves.

Normally, then, oral history is expressed spontaneously within communities, rather than as the result of prodding by an interviewer. Once this is recognized, it becomes much easier to see the opportunities that oral historians have, as well as the traps that may ensnare them. If we choose we can learn to be good story-listeners, to respond in ways that stimulate people to freely reveal their own views and values. To do this we need to become intimately familiar with the perspectives of the communities we are studying, so that we can bring to storytelling events the kind of knowledge that is expected of a local audience. As story-listeners we are in a superb position to discover and pursue subjects that matter deeply to the people themselves. By making our aim the documentation of their interests, whatever they happen to be, we act as conduits for the communication of their culture to the larger society.

Too often, however, oral historians rely on interviewing techniques which are foreign to normal patterns of speaking within communities. It is appropriate to use formal interviews, with structured questioning on prearranged topics, when one is tape-recording prominent personages about their careers; but these methods will distort the testimony of people like the oldtimers of Latah County, who are not accustomed to them. Researchers whose techniques interfere with the natural flow of storytelling never hear the history that is most meaningful to community members. This is the information that Glen Gilder hopes will be saved; and his view that it has been neglected until now is shared by a growing number of social historians who have turned their attention from the well-established record of major national leaders and events to the unrepresented history of American subcultures.

As Richard Dorson has observed, the oral testimony of these groups is “personal and immediate”; it is wholly different from textbook history, and it must be approached without preconceptions. “We have no way of knowing in advance what are the contours of this history,” he writes, “except that they will bear no resemblance to federal-government-structured elitist history.”2

In American society this history is usually communicated as life history. Each of us has formed a record of his own experiences and those of others who are significant to him, and willingly shares parts of it through storytelling, given the right circumstances. These personal accounts of the past develop in a continuing synthesis throughout our lives. In fact, we need to have distance in time from events to be able to understand their meaning within our life histories, just as professional historians require the unfolding of later events before they can interpret what occurred at a given moment. From all that happens to us, certain incidents and feelings are eventually solidified in memories that we find to be especially important. They exist as specific experiences in themselves, but they also represent, in a concentrated form, basic conceptions about the world in which we have lived and our own place within it.

The interplay of individual and collective meanings in life history has great symbolic value for the story-teller and his audience. Each story is actually an intricate communication of messages on many levels. As an example, let us consider one of the stories that Emmett Utt told during the visit mentioned earlier, keeping in mind that its symbolic dimensions would be clearer to Glen Gilder, an old friend and fellow community member, than they could have been at the time to an outsider like me:

Emmett as a teenager decided to “teach a lesson” to William Laird, general manager of the Potlatch Lumber Company. Local people were expected to pull their vehicles off the narrow dirt road at the approach of Laird’s luxury car, a Hudson Super Six, and on this occasion Emmett refused to give up his rightful half of the road as he roared through town in the family jalopy. The astonished chauffeur turned off into a watery slough, while Emmett, by escaping unidentified, avoided certain firing from his job at the Potlatch sawmill.

On the surface, of course, this is a story about “playing chicken,” an enjoyable prank. On another level it speaks of the rebellion of youth against status pretensions. It taps a widespread folk tradition of disdain for those who place themselves above common people, and affirms the democratic ideals of the West against aristocratic, monied interests. Within the community’s own past the story portrays an act of defiance against the area’s major corporation. Not long before the incident,the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW’s) led lumberjacks on a strike that won a great improvement in logging camp conditions but received little support in the company-owned town of Potlatch, where family men, dependent on the sawmill for their livelihood, were unwilling to oppose their employers.

Local oldtimers would hear Emmett’s tale as a commentary on this acquiescence, and would understand his action as a venting of community frustration and resentment against company paternalism. For Emmett, who had a very independent boyhood on a stump farm just five miles from Potlatch, it was hard to adjust to the constraints of the town and mill, and listeners who are familiar with his life would realize that this escapade is a moment of personal triumph. Twenty years later he resolved the conflict by quitting his job as a skilled sawyer at Potlatch for the greater freedom of being a farmer. Emmett’s story illustrates what I believe is the primary function of oral history—to symbolically act out problems and values of the speaker and his culture. Oral narratives are the most direct source we can find for knowledge of the behavior and beliefs of groups who have depended mostly on speech rather than writing to communicate their past. By hearing people tell of the range of circumstances they faced, the choices they made, and the traditions that have given them strength, we can discover the dominant concerns of American working people during the last century.

Beyond the inevitable local coloring of time and place, the elders of Latah County address social and psychological questions of great importance for our historical understanding. They speak, for instance, of the motives and hopes of those who migrated to the West, of families striving to become self-sufficient and secure, of the neighborhood as a source of stability and unity, of children’s rights and responsibilities, and of adult realities of work, family and community. Many of the tensions within their culture reveal the impact of national forces upon people’s lives. In Latah County these issues included drinking, which as a serious family problem and an illegal form of good fellowship became a local point for conflict and humor; the relations between country, town and city, with their differing social structures and attitudes towards status and success; the First World War, which made patriotism a subject of intense debate and caused a wave of prejudice against German pioneers; and the new technologies of gas-powered machinery, automobiles, radios and films, all of which brought changes to an established way of life.

Should we be surprised to find that Joe and Lou Wells, black pioneers of the Deary area, were loved by their neighbors and in time became the major symbol of solidarity within their community? Or that many oldtimers believe that the Nez Perce Indians were robbed of land that they managed far better than whites have since? That by teaching in one-room schools young rural women commonly became community leaders before marriage? Or that a large number of country folk regard the Great Depression as the final revival of neighborhood intimacy and pioneer spirit?

Such views run counter to the generalizations of most printed histories. But then, their authors have seldom thought it necessary to consult the people themselves. We have a chance to change this, by learning to listen with care to what others-and we ourselves-say about the past, and by seeking out the stories of people like Clara Grove, Catherine Mahon, Axel Anderson and Dick Benge.

Sam Schrager

August 1977

-

Robert Georges develops a theoretical model for this concept in: “Toward an Understanding of Story-telling Events”, Journal of American Folklore, 82(1969), 314-328. ↩

-

For descriptions of the differences between elite and folk history, and an excellent introduction to oral history, see Richard Dorson’s “The Oral Historian and the Folklorist”, and Henry Glassie’s “A Folkloristic Thought on the Promise of Oral History”, both in Selections from the Fifth and Sixth National Colloquia on Oral History (New York: The Oral History Association, 1972). I am much indebted to these essays for my orientation to the field. ↩