Episode 36 : Wilderness Boundaries Item Info

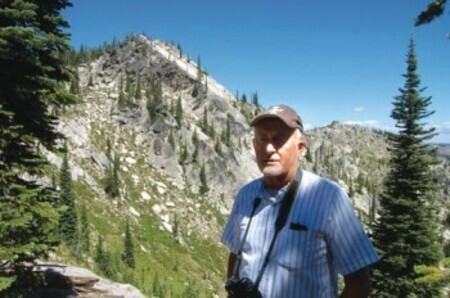

In this episode, titled “Wilderness Boundaries,” Dennis Baird, the co-leader for the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, talks about his view of what a wilderness boundary represents, both physically and ideologically.

Dennis Baird attended Michigan State University and the University of Hawaii, and obtained graduate degrees from the University of Michigan and Michigan State University, where he witnessed the very first Earth Day in Ann Arbor. While in high school and college, he traveled extensively in Europe and Southeast Asia, as well as serving for a year in Vietnam. When he finished school, he taught at Southern Illinois University and became involved in conservation, helping to establish the first wilderness area in Illinois: Crab Orchard Wilderness. After moving to Idaho in 1974 to work at the University of Idaho Library, Dennis joined the conservation efforts in establishing both the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness and the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. In addition to pursuing his passions for historical preservation at the UI Library, and fine wine at his locally owned business, The Wine Company in Moscow, Dennis continues to advocate for wilderness protection in Idaho.

Audio Clip

Interviewer: Debbie Lee

Interviewee: Dennis Baird

Location: Moscow, Idaho

Date: February 27, 2013

DL: Talk a little bit more abstractly about boundaries. What do wilderness boundaries mean? Are they, obviously, you can't build a road within the boundaries, but how do they relate to what's on the other side of the boundaries? In your opinion.

DB: Well, they're kind of a mythical thing, in some ways. It's like building a wall to keep trouble out and keep good things in. Not to keep people out, but I see a wilderness boundary as a place where society has put money in the bank and drew the line around the bank so everybody knows just how much money is available to be kept in there. It tells you, it sets the limit to the amount of money that you just saved. Because the reason for wilderness is not for recreation, although people recreate there. It's not for hunting, that's fine. The creatures that live in the wilderness don't know that they're in one, and probably don't care, but people know that society has made this decision to not use up some resource. To defer, maybe, because wilderness can be undone. A new congress can undo any wilderness area, and have it pillaged tomorrow. But it's a decision by society to set some limits on society. That's what those lines are. That's why the lines need to be big, in my opinion, because you want to save more than you need. You can't save too much. The way the world's society in general uses up resources these days, we probably are way, way short of wilderness worldwide, and even here in the United States, where we have a pretty good wilderness system, we don't have anywhere near enough, and we're going to regret how little we have. But the boundaries represent the size of the savings account. That's what my view of wilderness boundary is. What you can do in a wilderness, it's important. And the law. The Wilderness Act is a really good law, written by some great visionaries. Wonderful people. Howard Zahniser and Bob Marshall and... mostly Howard Zahniser and it wisely keeps things peaceful and quiet, and minimizes the ability of land managers to disturb things. It doesn't stop land management; it doesn't stop people's use. It just sets some limits on it within the notion of saving things. But the real reason to have a wilderness area and have a big one is that old notion that we as a society have decided that we're just not going to spend this resource. We're going to save this resource. We're going to invest it. Maybe we're going to be leaving, I would hope, a decision or two for our children. Wilderness is, the notion of setting aside wilderness is a sign of great optimism for one's hope about the intelligence of the next generation. You always hope that your kids are going to be smarter than you are. That's always my hope anyway. I think it's going to turn out that way. You never know, but if they're smarter, you've got to have some decisions left to apply those smarts to. If we've made all the decisions as far as natural resources go to use up everything, to modify everything, to degrade everything, then as smart as they are they won't have anything left that they can decide on. We ought to, we owe them the maximizing the places where their brighter intelligence, their smarts, better than ours can be applied. So that's the other reason for wilderness.

DL: There might be things in the wilderness that we can't see now. That need to be studied, and looked at, and valued that we in this generation cannot even see it.

DB: No. We're kind of stupid. We don't have a clue. There's all sorts of things out there. There's certainly anthropological things in wilderness that we know nothing about. In my wandering around the woods, and yours too, in all weathers we've stumbled upon, well, what's this? And it's human. An artifact of some sort that we have no understanding of. There's any number of American Indian sites in the Selway country that are totally undocumented, totally un-understood, not misunderstood, totally no understanding whatsoever. I've seen lots of them. You've seen them. Other have seen them. You look at them and say, that's interesting. What do you suppose that is? Well, that's an obvious thing that's out there that we don't know anything about, let alone the best way to manage it, so one would assume that if you don't know how to manage it then you'd try and keep it so it didn't need management.

DL: Right. And those artifacts might be anywhere on the landscape in the United States, but a lot of what we have has been covered up.

DB: Yep.

DL: So we'll never see it. With buildings, and roads, and farming and stuff.

DB: And even in protected areas that's happened. There was an interesting study on wildlife habitat that was devised maybe ten or twelve years ago by some scientists. Which creature was the topic of the study doesn't matter, but they looked for some undisturbed sites around the country where this animal lived, so that they could use them as a base line. This was an undisturbed habitat, and they were confident that the National Park System have a vast amount of sites that fit that bill. Undisturbed, wonderful wildlife habitat, and quickly discovered that even within the National Parks there has been so much interest in development: lodge building and road building and making things easier to reach for tourists and so on, that many of the most valuable, best possible sites for the study of this animal had been obliterated. Even in the National parks. And the same study concluded that the very best places left for that kind of study, if you needed a baseline, undisturbed site, that had been undisturbed for a long time, almost all those sites were within the National Forest Wilderness Preservation System.

Gallery

- Title:

- Episode 36 : Wilderness Boundaries

- Date Created (ISO Standard):

- 2013-05-17

- Description:

- In this episode, titled "Wilderness Boundaries," Dennis Baird, the co-leader for the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, talks about his view of what a wilderness boundary represents, both physically and ideologically. Dennis Baird attended Michigan State University and the University of Hawaii, and obtained graduate degrees from the University of Michigan and Michigan State University, where he witnessed the very first Earth Day in Ann Arbor. While in high school and college, he traveled extensively in Europe and Southeast Asia, as well as serving for a year in Vietnam. When he finished school, he taught at Southern Illinois University and became involved in conservation, helping to establish the first wilderness area in Illinois: Crab Orchard Wilderness. After moving to Idaho in 1974 to work at the University of Idaho Library, Dennis joined the conservation efforts in establishing both the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness and the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. In addition to pursuing his passions for historical preservation at the UI Library, and fine wine at his locally owned business, The Wine Company in Moscow, Dennis continues to advocate for wilderness protection in Idaho.

- Duration:

- 9:33

- Subjects:

- 1964 wilderness act boundaries

- Section:

- Wilderness Voices

- Location:

- Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (Idaho and Mont.)

- Publisher:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Source:

- Wilderness Voices, The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project, https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/

- Original URL:

- https://selwaybitterrootproject.wordpress.com/2013/05/17/wilderness_boundaries/

- Source Identifier:

- Selway-Podcast-ep36

- Type:

- Sound

- Format:

- audio/mp3

- Language:

- eng

- Preferred Citation:

- "Episode 36 : Wilderness Boundaries", The Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/sbw/items/sbw327.html

- Rights:

- Copyright: The Selway-Bitteroot Wilderness History Project. In Copyright - Educational Use Permitted. For more information, please contact University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives Department at libspec@uidaho.edu.

- Standardized Rights:

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/