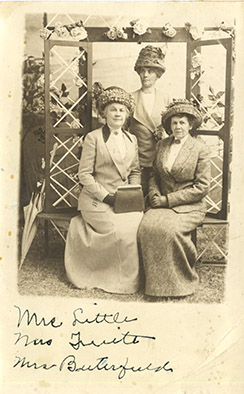

Edna Johnson Butterfield Interview #1, 10/11/1973

Laura Schrager: Edmund Johnson Butterfield was born in 1890 at Woodville Community, north of Harvard. She lived there until age 20, when she married Orval Butterfield and moved to two miles west of Harvard. On this tape, Edna Butterfield describes her parents arrival in the United States and their move to Woodville. She talks of her father packing groceries up to the hoodoo miners and in her house, which was a halfway house for travelers from Harvard to a miner.

She also mentions school entertainment. The 1893 depression, and Doctor.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Whom she writes about a mile from here. My oldest daughter.

Laura Schrager: You're. You're her oldest daughter.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: My. I'm sure you don't know her.

Unknown Speaker: Oh, yeah, he knows me.

But I knew all of you over.

Laura Schrager: So I thought if I moved.

Unknown Speaker: Around here.

Laura Schrager: Know.

Unknown Speaker: Up above Harvard.

Laura Schrager: How far did they live? Near where you used to live with them.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: They lived away from where I used you.

Unknown Speaker: Have you been up to our program? Where you are, ma'am? Mrs. Masters? No, ma'am. No. Well, that's where they used to write.

You know where I up?

Laura Schrager: No, I don't know many people around here, so.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: They need to be there for you.

Laura Schrager: so I can. I don't remember much of what we talked about. About your parents lives, But, your father was from Sweden, and he came over here.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah.

Laura Schrager: Do you know why he came back? Do you know why he came?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, just to change it. Just to see if he could do better again. Usually only 17 when he came over. Then you never show any of these old folks after they.

Laura Schrager: No one came over with him.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: He just know that it seems. And I never as near as I know he was just acquainted. He had a way to show for. And he came over the Grand village. Okay.

And he just stayed at home.

Laura Schrager: He he he first came to the Midwest, right?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, the first oh seven to little noise when he came across.

Unknown Speaker: And.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: And he worked for the railroad and railroad company back there for him.

Laura Schrager: How long was he live. in the Midwest before he met your mother.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, now that, I don't know him.

She was, he was 32, and they were married, and,

I don't know how long that they were here before he married. But they were married in Michigan.

Laura Schrager: Do you know anything about your mother's family?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, yes. Yes. My, my mother was born in Canada, and, Her her parents came to the United States. Oh. I suppose in about, 18.

I would say about 1870. They first came to they they came to Michigan, and that's where they were, where I do everything. And their father and mother, right. In Michigan.

Laura Schrager: Do you know where her.

Unknown Speaker: Father and mother got you in that what, you thought that?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes. My.

Unknown Speaker: You know. But didn't you mean your grandparents? No. Did you meet her father and mother?

Laura Schrager: Yes. Yeah, that's what I was asking.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: because my father and mother and. They were married in Ludington, Michigan, and they were married in 1883.

And,

And then he came to Idaho in 1888. He when he came here and and where she came the same year, they became really good. And then she came later.

Laura Schrager: How come they move to Idaho?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, they were just friends. He is from Michigan. That was out here and had a share. He had taken up a claim there, what they call preemption, and they taken up a plane. And this federal and covered and found a wonderful country. This was and if he could do that they could get him some land and that he had not.

Laura Schrager: Did he get the land, your father on a preemption claim or was it a homestead?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, I it wasn't the one. They were something the same saying.

Laura Schrager: Oh they're the same.

Unknown Speaker: Okay.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah. He, they want a preemption at homestead at that time.

Laura Schrager: What's the story about your father being shot.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: I wish we never were married into the day you were on a railroad trail. And When he came out courthouse and being at the trial. Yes. There was a drunk man shot him and trapped in the right side of the neck. And he didn't have a good use of his. Oh, right. Said he would have had it.

It was. And that was the year they were married.

Laura Schrager: Now, who was the drunk guy that shot him?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, I, I don't know who he was. And, yeah, if they knew, I never heard them say that he'd been arrested on trial.

Laura Schrager: Yeah, I saw that in my notes, but I've forgotten the story.

So did you, your parents came out by railroad when they came?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes.

Laura Schrager: Did they bring much stuff with them or.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: I don't think so. Although I don't, I don't definitely know, but I don't really think they did bring my children.

Laura Schrager: How did they end up, homesteading where they, finally kicked away?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: I don't not have him. They beat my father and this man back in Michigan, and this man wrote in the courtroom, what a wonderful country this was. So, he, in that very state, directed him.

Laura Schrager: How'd they pick the, you know, the the, actual place that would fell was that were your, his friendly,

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, he lived near there, and,

Laura Schrager: Did your parents ever talk about, what the first years were like?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Did you did.

Laura Schrager: Your parents ever talk about what the first years were like, getting started?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, yeah. And then since they were mostly came over there and, and, you know, just striving to get along, that was all. And. It.

They never had a lot to say about it, but they did.

Laura Schrager: What did they did they start clearing land immediately when they.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: When they had to and they had neighbors and that they had those times. Why they had these old fashioned country dances with, for amusement, you know, on and their, their whatever and letters. And there's just about, the only amusement there was the dirt.

And I can't think of anyone else. there's some I live around here. Now that would've been here on my porch or came. But as they quick, they're all gone. You know, that's a different name to go.

Laura Schrager: To. How did your, parents get by in the 1893 depression? Sucker. Pretty hard here.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah, it worked, but they, they had a few cattle, and my father traded a cow for a three, six week, 200 pig chickens.

In 1893. And, They had their way. They had their own meat.

And their. I guess I'd laugh about that. And, of course, I have a three year old. My three year old. But I have heard him talk a lot about that.

Laura Schrager: Did they farm very much land first?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, they didn't farm very much. It I think they had 160 acres of space. But I don't believe they found more than 50 acres of it.

I don't think there were 50 acres, which I think 30, 40.

Unknown Speaker: And they cleared up some more ground afterwards. But then my grandpa was. When did you start? Oh, God. Community. And then they had the post office up there.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah, yeah, I know what they said back in the news. He had three horses that he did. They ride one and lead two. And if all that took their first. Well, they're it into the hoodoo line. And I know they're taken. I mean they're in 1897. And I don't, I don't know I don't think they started too much more.

And before that.

Laura Schrager: How long did you do that for.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: How long did I.

Laura Schrager: Know? How long did he do that for your father? Pack.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, he must've done that for 4 or 5 years. And then finally, they were sure they got a wagon around up in there. And they. How on the strip?

Laura Schrager: Did you father do that, too?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, you own them? Yes, but they did. But they. Yeah. All the classic wagon rolled up in there to look good so people could get in there to mine. And.

The head was tickled. Do you mind up there. Have you been up in the country?

Laura Schrager: Yeah. I've never seen the mines, though.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, you see nowadays too. So you. But it it was the one mine they had which was made for mine. And myself. I never got to be in there at all. Oh, yeah, I bought about 22 ago and I was a big, you know, I was down.

Laura Schrager: And how many miners were up there?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Or they just go and come and I don't know, I suppose at one time it might have been 20 altogether, but I don't think there was.

Unknown Speaker: More than that.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: And there were a few Chinese. I know, those two Chinese that I knew.

Laura Schrager: Who worked up there in the mines at that time?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah, we.

Laura Schrager: I thought there wasn't. There were a, It might have been earlier than that when there was a lot of bad feeling between, which was a bad feeling between the Chinese and me.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, there wasn't at that time. They might have been earlier, but at that time, there were for my father, picked groceries and stuff up to those Chinese and, You know, for a fact to they always drive to see which one was gonna have him for Sunday dinner. He took me and family and they always try to see if I was going to have him dinner.

And he ate at the Chinese studios.

Laura Schrager: What would he how would he arrange the pack or would he, go up there first and get their order.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Whatever he. Yeah he had what a place to get the groceries and they bring it back from here. He'd bring it here with a wagon load with a wagon and then he, I have to put it in these pack horses, pack it up in there to.

Laura Schrager: So it would probably take him, two days or.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No. He'll and make it from here. Well, if you went to get the groceries, that was a day, a two days trip to go to college for that first step in your 30 miles. I may go down there and get groceries and and get back. And then, you did take him a day to go from here up to do with his groceries and come back home.

Laura Schrager: Well, how often did he did he do that every week or through?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No. I think you went about every two weeks.

Laura Schrager: Did the miner stay up there in the winter?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes. He didn't. I talked to.

Laura Schrager: Did your father bring them groceries in the wintertime also?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, no, they could, horses.

Unknown Speaker: You know.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: The usual way of driving there. But in order to him. Well, there was no way driving up there, but he was back in there with the horses. So you get to take.

Laura Schrager: Do you remember what, your house was like when you were a little child?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Do I remember what.

Laura Schrager: Like the house that you lived in?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes. It was a log house. And, The. We had just a rough boards for the floor, and it was far enough apart so we could draw up a pen and sometimes a pencil down to there and dirty work to get it. Get it out.

Laura Schrager: You do that once a year.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh my gosh. If we happen to have a draft something down there that we wanted, then they'd take it board up and get em up and.

Laura Schrager: How big a, house was. And.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, I don't know the we're sure. We had to. I think about five rooms. And, the main thing would I remember as a child they built a cellar under the house. And this cellar, they made it what I called and what we thought at that time, a bunch of lower. And that floor was that they'd expect, lengthwise, you know, and then they'd put the.

Leaves the smaller side up and the other, but the floor. So we had that in our shadow. And I know we hid that for years. I know we had a champion, 1901, but my baby brother was a baby. I don't know about that, but they had,

Laura Schrager: Stand that wasn't in the cellar. They put it.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: In the cellar.

Unknown Speaker: You know.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes, we did, stranger. We had footboard. They were foot wide. The board and the house, the, the floor counter. It was just a rough floor. This. They fought with these boards with your number four.

Unknown Speaker: To.

Laura Schrager: Did you have, more than one, fireplace or heating stove here?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, they had a heating with stoves. We always had one on the kitchen and on. And the part of the house, heating. So. And we burned that for sure. What was it at that time?

Laura Schrager: When you cleared land in those days, was, was it was it worth the effort to take it to market.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Or put the.

Laura Schrager: The lumber, the trees when you cut trees down?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, they would later sell storm melt around that wood. So I don't know. And, there's one thing I had to, down to Canada. but, the, at that time, they could cut wood, wood and four foot planks and how that to push and so on for $4 a cord. Oh, 30 miles.

Unknown Speaker: Hour of hard wood is.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: A hard move to burn stoves down.

Laura Schrager: Doesn't sound like it'd be worth the effort.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: It don't. Now, they don't sound like it now, but at that time we had to do it. They were glad to do it, to get some groceries. They had to something to buy for it. And.

Laura Schrager: Who were the people in Palouse that would buy that? But who were the people that would buy the wood?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Why are you go and have a free. Yeah, well, they wish the hell out of the furnace. So. And, I don't know what they thought some of the Garfield, but that,

Laura Schrager: Were there many families that lived near you where you lived?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, yes, there were several that, lived in above us soldiers who school. And, when my brothers started school, my brothers was older than I was, but they were strict. They had to walk about two miles or two and a half to school, and they had a school of, 3 or 4 months out of the year.

Well, very fun. I got my sister and I got old enough to go my father went and, with the other man. And where her little log schoolhouse says that. Because as little girls, we couldn't walk that distance. And, that's where we went to school. We.

And that room, I don't think, was more that, Probably 14 by 18, do you, Mary?

Unknown Speaker: Okay. Well, school after I got.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: That's what I get.

Laura Schrager: My education is it's still standing.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, they, And a government man here a few years, a few years ago to see me and talk to that. And he said he wished he had to know him in time to have had that building preserved. But the father bought it for them, and.

Unknown Speaker: You mean the schoolhouse or the bunkhouse?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, yeah. There's a well, I don't and there's the fish schoolhouse. But for that.

Laura Schrager: How many, kids went to school in that, schoolhouse when my.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, sir, there was two years. It was just my two sisters and I, they quit school there, and, some of the time, they'd be 6 or 8 with just the people in command, maybe for a year. And then they were gone. And as far as I can remember now, as far as I know, they had one boy leaving that, for school of same time I did.

And, you know, I had to.

Really slow down or not, down or dad and say.

Laura Schrager: What's the name of the young man who's around?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: The man that I remember, it's Harvey Leeson. Is there some place?

Laura Schrager: How do you spell that?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: I couldn't hear that. You. I the wso where? He. And he was still alive here. Just used to see me here. this last summer.

Laura Schrager: Most of the families that, came in and, didn't stay very long.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, they couldn't make it good, so they had to go where they could make a little hmhm.

All right. clients.

And and this was mother daughter.

Laura Schrager: I mean, the whole family.

Unknown Speaker: Almost every home.

Town was paper.

did you want to come back? Maybe there was somebody back in there.

Laura Schrager: Who? Do you know why my. Your parents were able to make it and other people weren't you?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: I know, I find it now. I think it would be.

Laura Schrager: Yeah, I don't know.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, just because they were determined and they brought their cows and milk the cow. Oh, it's so you butter cream left. So anyhow, they didn't make it last time. And children had you know, children didn't have the luxuries they have today.

Unknown Speaker: One day's good, the other.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Day they didn't get. Oh, no, I never did go. Very afflicted. I managed to get to that 10s fast.

Unknown Speaker: Yeah, yeah, I know what you wanted to share. Three cold cases. You. Last night we went to do it.

Laura Schrager: What? What were your jobs around the house? I what were your jobs around the house?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: My job. Do they handle all your stuff? I don't love it.

Unknown Speaker: Oh my goodness. Oh I think I have.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: The oldest girl was $5.

Unknown Speaker: Oh, no.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Technology helped. My mother got to tell us.

Unknown Speaker: Live with. Oh.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: And another thing she used to keep boys. You and we and we cook for them. And help me better than that boy Malcolm.

Laura Schrager: And how was. You know, you're close schools. would it would you consider that your place was right in what felt was wonderful?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: yes, it was my father. That name would there.

Laura Schrager: how do you name Woodfield?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, they all used to. Do you like that name? So he there change to himself? You know, Bobby.

Laura Schrager: And so now there was a post office and would fill.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah.

Laura Schrager: Where was that? Was.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, it was a shack. It's down there on that flat. You know what I, what fairly I do.

You know.

Oh, sure.

Unknown Speaker: I was.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: So there was no account or anything except I thought because he had the post office in the house right.

Laura Schrager: Who ran the post office?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, my father did work. I had one, but it was some other one before he kept it all.

Unknown Speaker: Thank you. Few people. And then.

Laura Schrager: Now you're. Was the road to a minor from Harvard has not always been in there. The road from A minor to Harford. Yeah.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: yeah, that was just, kind of a pack trail was one of their big time. And, and then, place what they called about a halfway house. It was about halfway between Knoxville. Oh. girlfriend's. my idea and, why they come out here to her adventure and last summer. Stop there or not? But.

Unknown Speaker: Yeah, research and, update.

Laura Schrager: Was that it was pretty much a two day trip to get from a minor to Hartford.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah, I don't know. We never went to my dad. They could have. We always come. They thought it was.

Unknown Speaker: Santa.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Claus show. We never I never went to a I never was to a married life where I live now.

Unknown Speaker: Where in Volusia.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: County.

Laura Schrager: So how did people know to stuff your house? Did you know that they.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Could get I don't know, I, I could, but I suppose you can. They just can. yeah. You got a habit of it, you know, go through the country and then there's, there were some, took the plane was what they call. Well, as I said, the timber claims or not, then they, you know, when they could hold their timber claims at that time, and they'd have to be on that train overnight once a month.

Unknown Speaker: Yeah.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, then they come to, play. They come to my place out at my father's grave and stay what I want, and I and I go on next day that I play them two days. You see, on they land me and then they all. I have to do that watch every six months.

Laura Schrager: Every once every six months is all.

Unknown Speaker: You can take some common ground plane grass. Yeah. Work. some rain.

Laura Schrager: Now, you had a bunkhouse for them to stay in, you know. Where was the bunkhouse for travelers to stay in?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, so he had that for a place for the man to sleep and that was there on my father's land and fish for the man to smoke them straight for I think it was. He didn't have room in the house for.

Laura Schrager: For him it was mainly just men who would come through. Who?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, mostly, yes. I don't know why we had women.

Unknown Speaker: Well, he wants me up off. No, I it looks like you move it.

Well, you know, my mother used to holler.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Out of that and say.

Laura Schrager: Were there many people that, that live beyond your house toward a minor? Or were you sort of the last house?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, I say they they were factory up through there and had people lived, you know. Well for my folks did that went and homestead. So down and so I'm just stayed till like it. Let's I can't prove up on my my for my brother faces there after they proved up on. So the land was theirs. No one other places he.

Laura Schrager: So most of the people that that came were, were just single men who were,

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, most of them were. They were some, some that had families up in that who knew country. It was one man I knew who. I said they had six children in there. And finally the government kind of took it in the hands and let them go out where they could send their children to school and that they were here just living up there.

That was all. And they had six children, and the government headquarters made it. You can go where they could tell the children to show they like that. There.

Laura Schrager: Most people just stayed overnight one.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Night at my place. Yeah, right.

Unknown Speaker: That's true.

Laura Schrager: What would happen if they got caught in snow? Do they often, you know, get caught in a snowstorm or something and have to stay long?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, they never, ever seen them. They didn't. That didn't happen. Yeah. But it.

Unknown Speaker: Very much.

Laura Schrager: How many people would come through.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh I wouldn't I wouldn't have any idea how many. Some days it weighed maybe 1 or 2. And sometimes it'd be a few more. And they just it's just a hassle if we go through that trying to, to go somewhere.

Unknown Speaker: Else.

Laura Schrager: It sounds like there were a lot though. I mean, there were, you know, people everyday, did they most of them stay at your place.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Where most of them had, places. Other places. And I were some of I was just too long to see the country to see if they want to locate there or not.

Laura Schrager: But a lot of them stayed overnight with you.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, yes.

Laura Schrager: Now, you must have had a lot of company.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: What? We did it was one year that my family never sat down to a meal alone. There was always some low 50.

Unknown Speaker: Some.

Laura Schrager: Well, I'm surprised I didn't think there'd be that many people coming through.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Because, yes, it was. It was surprising. And of course, they were staying well up until I after I was through school, I had about these 3 or 4 months school a year.

And back then they got there. So they had regular school that year. But when I was in school we only had 3 or 4 months a year. Yeah.

Laura Schrager: When did you go to school?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: In the summertime. Some. Oh they, they have a they they'd be a college teacher right. Or something I would call that college would come teach you that there is a distinction. In that time they were paying the teachers $35 a month. And the teacher and then the teachers should have paid $10 a month for board. So you see.

But but it made them close to making house.

Unknown Speaker: To.

Laura Schrager: See what they can live on now. Or it could live on them through some board me for $10 a day and being presented through. Did they board with you? Who did they.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Board? Yes, that was my mother on board.

Unknown Speaker: Several of.

Laura Schrager: For most of them pretty young. The teachers.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Motion were. Yes. And were they? They had most important girls that were just right to my. I would go to school with me for. Group and.

Laura Schrager: Was Harford was the, nearest real town and but Harvard was the nearest town to.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Go to Harvard with their their.

Laura Schrager: And when was it? When when did Harvard start growing as a farmer?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Started growing well, approaching about half.

1900. Were, Rest were about 1908 or 9 when I met the Harvard.

Laura Schrager: So Harvard didn't start growing until they put the railroad in them?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, no, no. And there was no town at Harvard, but they were able to.

Unknown Speaker: Let's match.

Laura Schrager: With Princeton.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: There were a bunch. There was an older town, group two. And years ago when, it was part time and there was an old setup, but they were shy. They had the post office and, the heavy sort of mail and things there. And then I would say. Would be somebody else give me an input. Okay.

He left and then there was another party. Come in there came.

Laura Schrager: How come they changed the name of the town from Starner?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, I don't know how it came because a man I started name was Sharon, who? And then when they changed it, they changed it to, Grant. And then when Harvard started this turn, they they were having a college town together, and they were, at heart, function functioning Harvard. And then there was a little town up there.

Yeah. Okay, okay. I'm living there with Yale.

Unknown Speaker: Used to be a Stanford.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah. At Stanford. He lives in a little town that great. And that was, in the a little later years.

Laura Schrager: Do you know why they got it into their heads? To name everything after colleges round up.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: And there was very. There was a man by the name of dearie, and he came in there and, he located the place for dearie. And then he was the one that changed, had these themselves all named after College Town.

Laura Schrager: You know, he didn't change. Princeton didn't get its name. That was all.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Right. And student. But Harry.

Unknown Speaker: Refused to.

Laura Schrager: Did you go, do you ever remember going into, Palouse? did you go there very much?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Maybe walked over 5 or 6 years. Well, I had to drive at 15, and we just didn't get to go and march in a while. My sister and I go with my father down. Manford down there. He did, I say about a year and a shopping.

Unknown Speaker: And then we come back home with it.

Laura Schrager: What do you. What do you remember? Balloons.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Balloons? But it was a bigger talent, you know, things that are down on paper now. You.

Laura Schrager: Was it a pretty bustling place and bustling? Was it a pretty bustling place where there are a lot of people.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: From what they would from over there, and more or less. So that's just a location at one time I can remember in French number seven, someone's.

And then and there there's lots of fruits to the north. Process. And there's so much drinking going on in those days. And. They should drink enough now. But I don't know. It seemed that there was so much going on there.

Laura Schrager: Yeah, it sounds like from what I've heard, that it was that it was really pretty bad. But then the drinking.

The.

You mentioned that your your parents, sold. So butter and cheese. Where did they sell that to?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: You get a packet of them to hoodoo to and sell us and and up there, you see, they'd mind you make a little. All because I, I grew up in. And you take these butter and eggs and cheese with whatever they had up there and, and then they'd send the same with the groceries to me at a police station and face.

Laura Schrager: Were your parents ever able to to leave home together?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No. Sounds. 60 things we all had to be. But one of them had to be there. Yeah, they're not bad days. People can go somewhere and arrested and the whole family can go down there. But those days and they just thought they could go and.

Laura Schrager: What do you remember, about, you know, what kind of livestock you had around the place, about how much?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, we had horses and cattle and sheep.

Laura Schrager: how about how much of each would you have?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: How much what.

Laura Schrager: How much of each would you usually have?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, they never kept more than 10 or 1250 cattle and death. They keep for horses. They need to work with me. oh. Maybe 4 or 5. And then they keep maybe 10 or 15 sheep.

Because the sheep they did from Lebanon. And so we were lost.

Unknown Speaker: And.

Laura Schrager: Did your mother card the wool or anything or did.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: My grandmother did her that my mother did that. My grandmother did.

Laura Schrager: She didn't live with you, did she?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: She.

Laura Schrager: But she didn't live with you, did she? Yeah.

She came out with you from, with your parents. Rather.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No. she came with a big. But she came up to my parents, and she pretty far. It will make your lunch back and.

Laura Schrager: That's something no one does anymore.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Her.

Laura Schrager: Did most of the, The girls mainly work indoors, and the boys work, outdoors with this livestock.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, yes, I think they did. And more so than I do now. The women work up for dogs more than I did. Set,

Laura Schrager: Did you didn't help fund any kind of harvests or anything? Very much. They didn't for on the harvest dirt or or.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No. And we didn't have much. Very interesting. And at that time there was no farmland transfer and we have little they've kept some hay for the cattle, horses for winter. And that was rough. They did have an income, but nobody knew what was up in there. It's just rife with food.

Laura Schrager: Is that mainly when you grew was hey, hey.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah, yeah.

Laura Schrager: Was it the wild Timothy lot?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: It was. Was, you know, he finally got some food up on the market tank. And the fact that it was.

Unknown Speaker: Mostly wild.

Laura Schrager: And you didn't have to reseed that. Did you.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Write about so much.

Laura Schrager: You. How would they harvest the Timothy? Would they how would they harvest it? Would they just.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Make it more. All right.

Laura Schrager: And then there were they just get it in big piles and leave it right.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: There, stack or put it in the road. But and I happened to have.

Unknown Speaker: To.

Laura Schrager: Did they like, rake the, for the, the stacks of hay into wagons and then take them to the barn inside.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: How years.

Laura Schrager: Would you get help from the neighbors for doing that or.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, no, I never had nothing about I could do their own and they wouldn't do a lot of harvesting and things like they do now.

Laura Schrager: Did you used to visit with, other families?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Very much, yes. They visited more than they do today. They don't want to fast to the other. And, they have, what they call these little party dances where, mostly Friday or Saturday night, but a budget. But go to a house and play and dance and, and there's a few musicians that would play and.

Laura Schrager: Mostly fiddlers.

Would you? You came along even when you were a little kid. Did you went along even when you were pretty small?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah. I wasn't very large, but, Wonderful. My father, I am very I put him in more than 5 or 6 years old, but I went to see him with the letters, and. But he used to go. He really did quite a lot of debating at cemeteries like they did their stage. And, he could sit on their shoulder totally.

Anybody built him.

Laura Schrager: Where would they be? Home?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Or would they have? They had him the school houses.

Laura Schrager: They'd have them, in a schoolhouse pretty near you. Them?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yeah. Have for.

Laura Schrager: Do you remember any of the topics that they used to debate?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, I don't you don't remember any.

Unknown Speaker: And I wouldn't have any idea.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: no, I just don't remember any of the subjects that they, I know, my second oldest brother, he sure, he he he sure liked to debate and do those things, but of course, he's gone now. He's. I would agree with.

Laura Schrager: You would they announce it ahead of time and then people.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Just, Well, they might be Friday night ahead of time or something. It was just the neighbors that would do it. And they select teams to see which one could do the best debating and see who do the best. And then there'd be some judges to tell.

Unknown Speaker: Which one was the most.

Laura Schrager: So it wouldn't just be to two individuals that would speak on either side their fill. I mean, like there'd be, eight people and four people would speak for one position for for another, and then they'd judge which side one.

How long would that last into the night? That last very long.

Unknown Speaker: Oh, right. Okay.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Sometimes Kappa.

Laura Schrager: I want to I heard that, The the when they used to celebrate Christmas around here, that they didn't give gifts. That that wasn't part of Christmas.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, but, I really was celebrated. Christmas is, they had the schools. They'd have a Christmas program and f treat for the children, and it, you know, Christmas program got up by the children and then.

Unknown Speaker: You.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: And and they always really enjoyed that. even the grownups enjoyed it. I think the children's programs and using up those things for.

Laura Schrager: Like you'd have skits and, you know, clothes and you. Did, did you used to celebrate Thanksgiving?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, yes, I do, yeah.

Laura Schrager: I like them.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: I, we have 45 here for dinner last Thanksgiving. Now I have for, like a few rockets. We get away. They generally get together here at Thanksgiving for more. That Christmas.

Laura Schrager: Are there any other holidays that you remember that you'd celebrate?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, the 4th of July they have. They generally show by. We have, celebration. they had some old places that they used to have dances in the 4th of July that, that, that they. Okay.

Laura Schrager: Did you ever see, were there ever circuses or churches?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Circuses or, near circus? Did you ever went to. For sure. Ever been a circus? No, sadly.

Unknown Speaker: Like we went to some of the Moscow place, kids. But I don't know. How about you, mother?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes. They're here. Reissue. They used to be a circus in Moscow. I don't, I know then that one. They had one of those.

Unknown Speaker: If you wanted to go further back in my. I can remember.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: That we had, Yes. I used to have a circus place. I wish that was a wonderful thing for us to get to that night, would it? Have you seen anything like that?

Laura Schrager: Do you remember any medicine shows or.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No, I don't remember, I think you.

Laura Schrager: Were there many young families that lived around Woodfield, near Waterville? Many families that live near Wood Fell.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Right. Well, I don't was about a mile off the nearest. And there wasn't too many there. There wasn't more than 4 or 5 in that neighborhood. And the nearest road I know would have faced a mile. That would fail, wouldn't start until all the other towns were given. or had been going for,

Laura Schrager: Do you remember the names of any of the families that lived near you?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes. The most, one by the name of Mark. And and one of the name of Draper and Mason and Martin.

oh.

Since later. So I.

Didn't know they lived within maybe 5 or 10 miles. That. And there was it, you know, I can't remember. And Kim Smith and. But I think for her, every one of them are gone.

Laura Schrager: What did most of them do for a living? The same. Did they do anything different than your parents did?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Where to start with? That's about all I can do is go and or, tag on by and get more numbered and then get to, like, get more stuff and and love shovel Kirkwood ditch for today. And then. Come and show tours and.

Laura Schrager: Could could you get by, you know, year round just doing that, selling one cordwood.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh they could do. Yes. Because, they would tell us the road I could go I sometimes could do the Monday, but there was always a.

Unknown Speaker: Road where.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Anyone could get out. They had to. And in those days, the nearest doctor was 30 miles.

Laura Schrager: You know what people generally do when they got sick?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Requirements. They got well. And then children would write them to dad. I know one family that had a boy, and he had a lump on each side, and they didn't know how to cook and they couldn't afford the doctor. I he died were sure playground years that he died of cancer. And That my brother but he later off he had a, pneumonia.

And my older brother had died 30th March to get some medicine for him. And that would ride horseback. So it it really with children, I think parents could adopt in my home. But they survived best. They couldn't refuse it. Not very many. but there.

Laura Schrager: What were the the, common illnesses that, you know, were serious there? One, the illnesses that were really serious, especially for children.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, and and the fourth would be, diphtheria and fever and measles and whooping cough and cough was the name one.

Laura Schrager: But you in this area, you had all four of them, I mean, people.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Oh, yes, they had all four of it. And, no, but I was 11 years old. I had small.

Unknown Speaker: Pox.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: And that went through. And I had that butterfly with me or Joe, and I can remember that.

Laura Schrager: Well, how did they treat the, you know, how did they treat you for the.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: And the treat? You were just took care of you and, and, and did the best they could. And then you get over it, of course, you know, has to have proper care with that as well. They and they get over it and, yes, my father and, Two of my brothers and my sister and I, our two sisters, not all have to back.

They just took care of us. And my mother every year before we'd been vaccinated. So she didn't take it too. She'd come back. States where she came here to.

Laura Schrager: To. Do you know? Oh, you were in love with her. Did a lot of people get smallpox ear sounds like.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: No. there was a man came to my father's place and stayed all night, and. And his face was all about father and my father. Look, I kept looking. I am the all I said. Can I said, you must think I got some disease the way you're looking at me. He said, well, I didn't know, but your had.

He says you looked a bit like chickenpox or smallpox. Oh no, I haven't got that, he said. But just, you know, two, three weeks by ever since you could show for me and, and it went through the family that it was no fatalities from they all recovered.

And and.

All prove everybody's saying that, you know, they had to be prepared for and off to the best they could.

And they picked me. All right. Got ready to say that home remedies.

Laura Schrager: How did they treat it?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, If someone treated it with honey and,

And. Oh, gosh. So other things that way and and, but the Ohio sheriff and if they call.

Laura Schrager: On what they call what, what kind of sirup ipecac.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Their day, if you give them too much to do that, that'd make them and let it go up. That family stuff.

But that isn't what it is. Yeah, I used that.

Unknown Speaker: To them.

Laura Schrager: Are there any other memories you have of when you were really young? Of, You know, your family and things that happened?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: In your.

Right. You don't think of any right now. I don't blame you.

My other sister died when she was 14, but then she had kidney trouble. And we had a doctor for her that.

And.

I can't think of anything else. Mama.

Laura Schrager: What did you used to eat? Usually, you know, for breakfast. But what did you used to eat? Usually for breakfast.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Eating?

Laura Schrager: Yeah.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Well, la. I'm like to Irish. I'm. I'm not trying that we make Whole Foods have family. Okay, bread and stuff like that. And, so I make breakfast pancakes. If they were. Things like that.

Laura Schrager: Did you used to cantaloupe?

Edna Johnson Butterfield: Yes. Yeah. Whenever we can get it. And. But we had.

Unknown Speaker: Oh he played he played everything I don't know, he played more than usual, but he played. what do you call him? Mario. Mario part two. Yeah.

Well, they were musicians, some of their mannerisms. But these up here, there was music. You. You're right there. Used to play a violin a little bit.

All right. There it is. That's his brother, isn't it? Isn't that. Yeah. He's talking about. Yeah. Victor. Yeah, yeah, I used to play that. And the Albert's the youngest one. He was.

He was.

Oh, he played he played everything. Yeah, I don't know. He played more than Jewish horror, but he played. what do you call him? No, Mario. Part two. Yeah.

Well, they were musicians. Some of their mannerisms. But these up here, there were musicians. You're right there. Used to play a violin and a little.

Bit right there. And that's his brother, isn't it? Isn't that. Yeah. He's talking about. Yeah. That's Victor. Yeah. Yeah, right. You used to play it and, And the Albert's the youngest one. He was, he was a professional. He was really a musician. But he that didn't get killed. Or did he just died.

Edna Johnson Butterfield: You got a kid?

Unknown Speaker: he got killed. Yeah. Automobile. That's right. Yeah. He he studied music. He went to college for that music in college. And he was really good.

But we were, you know, we were talking about about the families being big. Is that is that true of most of the families around? When you were a kid, they were big.

They were big family center. Several big family. Hey.

That was held on, some on hold. that's three and Arthur, that's four. And Alice or Dorothy. Jenny and, and, eight and nine. They're nine.

yeah. They're nine. They're nine. And how many of the Halloween's.

Yeah, that I don't know. They're they're another big bunch. I don't know, I didn't know that. You hear about that many, do you?

So there must have been lots of kids running around all the same time.

But they're not there. Oh. She's there. There were 12.

There were eight boys and her. I don't.

Gustaf,

Just a.

Vegetable king. Oh, yeah. Yeah, I didn't know them.

The, when you were a kid, did you have, much work you were expected to do?

Oh, yeah.

I didn't, I don't know, not too much. Not too much. We we're going to ride along a little bit. We weren't drove any, our our dad, our folks didn't drive us too hard. They. But we work right along.

We were supposed to. We saw. Oh, he didn't. Holy, Holy. He was the one that saw all and our readers to saw transcripts of, we were they, power us.

Were you were you still pretty young when you first used a crosscut?

Oh, yeah. It started that way. Oh, look, you started that kid. Just little park.

Yeah, I even saw it up here, at camp 8 in 1910.

At bovver. The public saw it on the landing board, and we had to go.

Was, But we was. It was over there. They fellows, they play it out.

And we had to drag them out to the shed. Yeah. Get off me. I don't know them from them landing, you know, they they pull them tree length. Children. Hollow tree line, donkey. And then we were supposed to saw them on the landing. Oh, of the logs. And there were no blank logs either.

This was a picture for the first film. Moscow or any big, big town. There was ten Irish, seven. And that little squirt visual in the three, that's, the family picture of had to go to Moscow. Our family. Oh, yeah.

That's quite a nice picture.

Oh, yes, the pictures are mine. You can.

And it's this, this brother is is 99 years old. Zero nine. Then he was 74.

Your father has a very handsome beard. Yes. Full beard? Yes.

I never saw him without a bear. I don't think any of us did.

You know, I never. I don't I don't remember our picture. He had a all the time.

And then he was young. But, that's the only time we've ever been.

He was born with a beard. Did men.

And I got a picture of him. When he doesn't have a beard.

He does, but he was born in 1845. Know?

Yeah, he did that pictures. And then he was young before he was married.

I bet you've never seen that. No, I never shown that to me otherwise either.

It's. I never seen him without whiskers. This is a that's a wonderful picture of that picture.

Yeah. It, had been abused. our house burned up and all the pictures burned up, and, this was given to me after that by a friend of mine. And that it's been the kind of abuse, but otherwise. Oh, yeah. That's the old family picture. I see that,

You said, you were telling me a little bit that that a lot of people walked just about walked away from the places.

When they go first, there are several of them that walked away from the place. They come in here and homesteaded. They couldn't here a way to make it here. There are several of them went out. They built a cabin, lived probably a while later, and then they. You got mad, I guess. Went out. Then you. They had to be tough.

They couldn't. You couldn't figure on they were going to make it. You they'd have to figure. They had to make it. Didn't have no other place to go to stay. They were tough there. There was no where there was. There was no way around it. Some of them worked to keep their family on the farm. There's Anderson up here.

He kept there. He worked on it down, and she walked home every Saturday and back every Saturday afternoon from the afternoon. I mean, and he were done that all summer long. Well, you read that in the book, in the Arthur book. You have to say, Anderson. Yeah, I know that was right to. But today.

August Anderson.

No and no. Where does John Anderson's here live? Neighbor to Arthur Berg up here are the berg. It's not a book about that, but I heard him in his right. If they put that $0.75 a day way and then they never found it, it's a thing there. That's that's no doubt true. But then they used that up. I know that because she had she had to she was there all week.

She had to have some. So they used that up. It wasn't that they lost it. And then first then he Anderson he didn't lose any money, didn't spend the money there had of only her furnace. He didn't spend it just foolishly. No, I tell you, there's a they have to be hardy guys to stay.

And they had they had to figure on living off the land. They didn't do.

What about your your father? When, when when he came. He was he was he a really determined to make a go of it right here?

Oh, sure. You were determined. Is right. Didn't have no other place to go.

Cuz no chance he left the old country because there was no chance there. And he left Minnesota. I just thought he was going to better himself. I don't know whether you did or not. Then I guess you can just. Well, he couldn't make it there in Minnesota. Opened on 40 acres and tried to pay for it with nothing.

There wasn't any better there. They could. They broke up so they had a little Hoyt petrol had there took several years before that marked anything.

They didn't they didn't make any more or they didn't get along any faster there. They wrote a story in Minnesota than they did here. Same thing. There was no Margaret's. Nobody was buying. And then they could nobody had any money. They didn't have any money in Minnesota any more than they did here. Course they probably got their farming a little more and got a little more like the people here had better.

Better chance to eat than they did in Minnesota because they got away again. We're out here at that time.

Yeah. Here they ahead here would come right up to the house. Here they had fuel anyway. They had wood.

He wasn't he wasn't in woods in Minnesota. He was on prairie.

No sir. Brush interest. That was all Prairie, Minnesota. There was a brush that was out of us. There had some places in Minnesota. There was timber. But then not all. Not where they were. There wasn't any.

Timber. So maybe that's one reason he liked the sound of this better. If he was a German.

Well, he that's the reason they come out here, because there were dead and they were raised in Denver country in Sweden. So that's it. It's the timber that come from here you heard of this is, and his pure Hawkinson. You're describing this country for him. Described it. So they, like, figured there. Wood. And he was here.

Hallstrom was here. And then they figured they'd come out and try a good.

There people that that your father had known way back in Sweden. These, Hawkinson he'd known back then. He.

Yeah, they were granted freedom. They were from the same, same part of reading all of.

Their.

But there were, there were there was no chance there really nothing but rock. There was no ground to speak of. There might have been some lower land where they cut a little grass. There wasn't. And next to lake it was lake water rock in.

In sweet.

The way they described it.

Did did he ever say the name of the of the town or the county that he was, that he grew up near in Sweden?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. And then Venom Land, that's the same as, that was the same as, A county that's the same as county. And.

All right. Would that be the same state? I guess state that.

Maybe it's in between a county and a state?

Well, it if they're laid out some like counties and state. Now, let's see, where was it? Oh, that would be a state and the excetera that that would be a county. And that's where we come. Make sure I.

So it was made out just about like it is here. There wasn't much difference. I don't know what it as far for the difference in size because the country was smaller.

It wouldn't be a state because it's in Sweden. Sweden is the state. It must be a county. It's the same as a county. It he was talking about. They're from.

Vermont. Yeah. Well, when.

I would say that, it would be a county, of course, I don't know. It's a division in between.

Now. And somebody told me that it was kind of an between a county and a state because it was pretty good size, I think.

Well, I really don't know. So.

Well when, when he started here, did, did he, was there a house built on the place already that asked when he lived in, or did he have to build a place to.

You know, you, me, my dad. Yeah. No, he had the bedroom, the, there's nothing about it. It's a little bit of a cabin. And that is a very small one. Dude, that was all there. Just here. Just a just a one room cabin. And, so he built. He built his own cabin here is, quite an X man.

So he he slept his the other cabin that is built. There's never a wrong logarithm. They used it for chicken house after. And, and then he built a pretty good cabin. You slap, slap the sides rather than out both sides and draw them together. Whether draw, they had that groove one side and drop the other one down in and put moss in that groove and then drop the other one in here is plumb died.

That's the way he built there. Oh, they're all all the better built cabins are built badly.

They call that a draw iron. Yeah. That's called a draw iron.

Yeah. That's what they marked it with their their groove. Their groove. The lower edge. And then they put moss in that. It is something like a trough. And they laid a log on in that, that was plumb like you were warm. Never get in there. You didn't get cold in them. They had any kind of a heat.

So how big was the cabin that he built? Wow.

I was quite a big cabin. I don't know what what that would have been. About a.

14 by 16, I suppose. Or 16 by 16 or something like that. And then of course, did it. They lived there the first winter and then the next summer, where they probably built a little more than, I don't know how soon he built. But you see, Dahlberg, he lived down here on the. Where the first place down here on the creek.

And the next year he was here. He was one of them there. Promoters him. I call him his builder. And he he bought a sawmill and he started lumbering and and then, of course, we got logs down there and trade him for lumber. So there now there was, there was a trader over there was one. The trader did trade for anything.

It didn't make any difference foreign wars or whether he had any use for it or not. But he'd trade for and then he'd somebody wanted to buy it, sell it. Sometimes he'd sell for money and sometimes he'd traded to the next for. And there wasn't anything that he wouldn't trade for horses or cattle or lumber or long for anything.

He really, he was really the one that help this country up.

Why did that help the country, Why did his trading help the country?

Well, you they got from him and he got from them. It would help everybody.

Sounds like it.

It helped everybody if they wanted the horse to go down and trade him something for a horse. And if they wanted something there, if they wanted a cowboy, they'd go down there and trade him some for a cow. And, and that just kept around going around. And everybody was down there trading with him didn't make any difference what they wanted.

And they go and ask Pete for it. His name was Pete Delbert. They all he was known he was known the world over. I think for Pete. and that's a fact. He was the one that helped this country. If it hadn't been for him, I don't think. Had they? I don't believe how they'd make it.

What was you think the trading was good because it circulated. It circulated the goods that people had given.

Yeah, they traded between themselves. And that's all they had was the circulation of the goods that they had. They had now my mother, she she made she made butter. She was a butter woman. She, she made butter. If you got after they got a hold of a cow, well, they got a cow in the first winter they were here.

And after that, of course, they raised cattle. So they had 6 or 7 cows, five and six and seven calories all the time. And, and you see, they they were just turned out cattle. There was no herd law or anything. They just turned up and then the kids ran and got them in the evening and drove them home.

The cows got used to that. Mother ever. How many times I went out for miles to get the cattle, I'd have to stand on a hill or someplace and listen for a long, long time. And I heard the bell away. Then I went down there and got the cattle, and I sometimes had to go a long ways, too.

Just a little bit of a kid.

You had to do that every evening.

Every evening, but near every evening. Sometimes they'd be closer so I wouldn't have to go so far. But, otherwise we'd have to go and round them up and then drive them in every evening. You did the gravel and milk and. And that was, that was, that was the work we had to do. And that was after school.

And that was all of you. You couldn't figure on anything else you had to go with. I've lost my job to go and get the cattle. And I guess that was everybody's kids job.

Was it tough to get them cattle to to come back, or was it easy to hurt and back in what year was it tough to get the cattle herded back into the corral? No.

Once you found oh, no, no, the cattle, the cattle knew just exactly what you wanted. All you had to come and take and how are at them? And they'd all come bunch up and go in. There were. That wasn't any effort at all. It's just the effort was to go and get him and find him. And of course, they had a bell, you know, and you got used to that.

You could hear that bell for miles, as I used to stand clear up on the hill there and hear, hear the bell clear up on Joe five meadow. And that was about. Well, it must have been a long mile anyway.

And who's meadow?

Well, it's his Joe fires, they call it. His name is Joe five. He had a place up. Up here at Avon or below Avon there. And I used to stand over there on the Burger Creek hill above it. Herman Taylor's on a higher point. Now, listen, I could hear well, again, no. And I understand there for a long, long time.

And then they come in sometimes in the evening, you know, you could hear the battle for a long, long way to. And other times you couldn't. Then you'd have to go where you thought they'd be and walk around. You herded you heard that bell. And then you'd go down there and you'd holler at them and, they get on and they'd bunch right up and come on and walk right ahead of me home.

They always had a cow trail.

You know what you're saying? That your mother made butter.

Yeah, she made butter, and she made lots of it. And she packed it in five gallon jug jars. And then she didn't sell it, but her mother was made, so it didn't spoil everybody. And she didn't have any trouble. And sell her butter some some of the women had trouble resenting that about her, but. But she never did she.

She made good butter. But she really worked too.

She really worked all the butter. That's. That's the secret about having good butter. Herb butter to work the butter milk out of it. And she really did that. She worked. She worked the butter milk clear out of it so that it wasn't any in there. And then it kept.

Was that a really big job to to get the buttermilk out.

You good? That was a big job. That was a big job you had there. And there she had there a wooden spoon I don't know. But some, some of them yet I don't know. I don't believe we would have on the farm if a wooden spoon. She had deeper work and that work all the butter out of it or I mean butter milk out of it.

Yeah. And then they'd take half hour to churn it. she'd have to churn it. Oh, yeah, we'd have to churn it first then. And then work the butter milk. Oh, that was that was another job. But I she was a tough old woman.

How often would you make butter?

Oh, I really don't know. What was it? Once a week or remember a week. You remember how often she here?

Once a week.

Once a week, I guess.

Where sell it. Where did she sell it? And that's the stores I.

Traded that the stores didn't sell it. There was no sale. Traded it. You traded for groceries? Butter. The butter was cheap. And so the groceries you get, I think it was one time I remember we got 14 pounds of, our coffee. There are about in Lyons coffee. They. They're about to say they're running about the same price.

14 pounds for a dollar.

And I don't know what that was. Butter selling for. Gilly, you remember? But you remember what butter is selling for?

30

Cents a pound.

$0.30 a.

Pound. Okay. I remember.

Oh, it's not cheaper. No. He says he's asking how much the butter was selling for.

Oh. but, Not anymore.

$0.25.

I mean, the pound.

Yeah, that's that's about it. 95, I believe it is cheaper than that at times, too.

Yeah, but it was just a continuous trade. It just a continuous round.

Well, Pete Dahlberg, did he trade lumber? A lot of lumber for. Yeah. Goods? Sure.

Itrillionemember it trade a number for large. And then you got so much. He paid so much lumber, so much lumber, so much for logs in lumber. And you took the lumber and you sold him the logs. And that is. That was a trade.

How much bartering went on and trading like that. Did they barter very much back and forth to.

And do that one?

Did they did they barter very much? Do they argue about how much you think was worth?

No, no, there was no there was no way they had everything. It was a cheap. They didn't bargain at all that they didn't argue about it either. No, it's. Is it is it is. What will you take and what will you give me here. So. And if they didn't, if they didn't, agree where they go in the next fair.

That's the way they got along till till after the battle. I started hearing about 19, 19, 12 and 15.

Did Dauber do well? Did he prosper?

Yeah, you sure did. He did. He would have. He would have been rich. But he drank so much that he was. He was heard. He was a fellow that didn't keep no money. He just drank. And he just lived it up. Otherwise he would have been a rich man. He been like some of might. He'd have been well-to-do, lovely, well-to-do.

But he was a trader not only in one thing, but in everything. He created his money too, when he got it. If you get to it, got a name? Yeah. There's a feller redundancy. Come up there. Six horses? Yeah. Six horses and four quotes. Come up to buy some lumber. And he didn't have no money. He wanted to trade them gold for money or for lumber.

Sure. Government created. And then he sold the gold. He sold them around here. Everybody around here living at one. And how did Lynden get to go? I don't remember. Got one? I know he he had it a long, long time to and ever. And there were 4 or 4 people got horses. That's all it took you. So he sold them all.

He didn't have very long. I don't know what if he got any money out of it or if he traded them again. I don't. It just went right along with him. He was out there on the road trading all the time. We got 2 or 3 of horses from him. Then that we traded. He'd traded for them and then we traded logs for where my dad traded love for.

I don't know about two.

Two, if not more gold. Wasn't that 3 or 4 horses was.

We'll see. We'll see your. When you traded with him, did you did you do well or or was he pretty sure. I mean, we seem more likely to get the best of. No.

You know. No, no, he didn't try to get the best. He there is. He didn't with his neighbors anywhere. He was a neighborly guy at ten years. He just wanted to help his neighbor. And I think that applied to everybody that is that he dealt with that. He he just tried to help him. And.

And he was pretty well liked to show there, try to do the right thing with him.

Or you talk about, going to this about, buying groceries at the store, you know, training the butter. What? Besides coffee? Did did your family buy. Did they buy very much? I mean, did they get very much from the store?

Oh, yeah. They bought we bought coffee and all. sugar. Yeah. Everything we needed from near.

Salted fish and herring and everything. Oh, yeah. That's.

We didn't.

Did you have you church services? Did you have the church services in the schoolhouse?

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. No we didn't the school didn't. But then the, the, Bridgers, other Bridgers come in, then church services. Yeah. Just for near Sunday and Sunday school and then meeting after that service. I went to Sunday School and I was 25 years old. That's the only place we had to go on Sunday was Sunday school. I went to school and I went to Sunday school.

I found a five year old.

That's where I learned to read three.

And. And what? Little American. I learned English, of course. That was the week. Public school.

So I went to school. I went to school all the time. That is not, more on Sundays, more steady on Sundays. That happens every Sunday. I went Sunday school.

What was the Sunday school like? Besides, you studied Swedish, right? Besides that, what did you do in Sunday school? Did you learn scripture?

Yeah, well, we learned scripture. Do? Sure. I knew the Bible by heart for a while. For a long time, there wasn't a word in the Bible that I hadn't heard. Noone. But, I had forgotten. Oh, Lord, no, no. Since I quit.

No, I went to Sunday school. I was 25 years old every Sunday, but near every Sunday. There was nothing else to go to it if you stayed home or read work. Yeah it is. If you didn't go to school, you stayed home and work. Grandson. They gave me. You had to do something. So you went to Sunday school.

That was the only thing there was. You didn't kill there. It started then there. They had symbolic games up here, but I didn't go up there to them because there was just a by that time I was working, I was following horses, driving. I didn't I didn't take the horses out on Sunday. Much work. Well, I'd take one.

I bought me a buggy and sing. I used to sing at one horse, drove around a little bit, but I didn't. We didn't run around very much.

Whitworth was handy then. It is now. Jump into a car. I'm going to run off.

Well, it was was, Sunday School. Was that much of a chance for for socializing for the young people, or was it more serious.

Work.

Sunday.

School? Well, that was more serious. That wasn't so much. That wasn't so much socializing. Oh, no. We met, you know, we got there. We got it. Just like a meeting you go to and then you visit after the meeting, religious meeting. They you're now the seventh day Adventist. They don't do that. They don't visit after. But, this year, there's a mission.

They called it the mission. The church. They were all those visiting after meeting and visiting with, with with each other to.

Would there be a refreshments after the meeting or just people stand around and talk?

Oh, they just stand around rallying all the people that go over together with their young people. They'd stand around about an hour or so.

It'd be it'd be between 12 and 1 when we got back from the school, from the Sunday school, Sunday dinner, sometimes two veteran.

Of.

The fed and, it all depends on how much visiting there were.

Well, what about when did the meeting start? About what time did the service start?

So about 1030 or 11 or something like that. It didn't they didn't keep on very long. They probably were there about an hour.

where did the pastor come from?

It didn't have any passengers. Pastor Anderson. Even from the farmer farmers. As well. And was one of all manner from, all men. However, that that that was Archie Johnson's program that. yeah. Here he was he was, his mother's father and then ever was Johnson was was a teacher. Sunday school teachers do. And then it was a car loan and big, big car.

Like all in. He came from out there on Dry Creek. He he'd be teaching right from the road, too. He was a Sunday school teacher. But then he wasn't in our country too much. He'd come down once in a while.

Well, are you saying that the same guys that taught Sunday school led the church service? Yeah. Or were the same guys that taught Sunday school lead the church service?

Yeah, they did help there. There were church members. There were church members.

So there there were traveling ministers, though, that came through that hit the services most of the time.

Oh, you mean a lot of Sundays or most Sundays? There would be a minister there. Yeah.

Because sometimes there were travel. There would be at the meetings, there would be a ministry. But, not not that the Sunday school so much to them followers did it all their families go before the church services and then the church service take up. But.

When you had, when you had to minister at that at the service, would it be the same one every week or would it be different one at lunch?

Two oh, sometimes they come back, you know, but they, it was just, they were traveling through and it depends on how long they would stay there. you know, on so forth.

Well, when you say they, they travel. Yeah.

That's it, that's in the schoolhouse. But, the churches had regular was tired.

Yeah. I drove they didn't have for Sunday school. They didn't have regular ministers all the time.

There were no just traveling. Those ministers.

They. And they threw down here at the North Church. That was Alfred Johnson heading down. I don't know. Did you know.

About.

No. I know who they were, though.

Yeah. Yeah, they were, they were the Sunday school teachers. But then if there was happened to be a minister around there, you'd have them.

Were the schoolhouses used for entertainment two?

Well, what do you mean, a other?

Yeah, like, I mean get togethers without without there being.

No.

Overt church.

No. We. Yeah, we.

Had, we used to have their areas.

Yeah. Oh, yeah. They had letters. Yeah. Yeah. That's right. They didn't have letters.

Do you remember what those literary were. What, what they did their the literature. Yeah.

No I don't read. They were discussing drinking and fighting.

There you know depends on how while the crowd were.

And then I don't know what discussions there were I can't I didn't go to literature too much. I was too young. But,

What about, dances or parties?

Well, they didn't have that in the school schoolhouses. There.

They didn't know there had been a school houses because they had benches, you know, that had to be moved. There were they were tightened, right? No. So they didn't have dances in the school houses.

Were there parties at at people's homes that were there. Were there parties at people's houses?

Yeah. Oh yeah. There's house parties in lots of places. We used to have a, we used to have house parties or down around there where we lived.

There dams there. We didn't at the house parties. There was a lot of them around.

And that was later. That was later in the later years, one when we were kids. And then it was then it was a Sunday school. And in the later years, then we had house parties. Bird birthday. House bird.

Birthday.

Yeah. Birthday dance we did. Yeah. That's. Is. That was a certain bunch mostly. I mean.

That was. That's a big that's wasn't a very big crowd.

You six, seven, 6 or 7 couples or something like that.

In that they lived very much the way we did. Yeah, I guess so. That's the dog. A lot of money. Where did you get that? from?

Yeah, we did that. Are you a no no, but I, I talked to it. When I see. the,

Yeah. Yeah. Go ahead and.

Finish. Did you know, did you know Big Anderson?

Oh, yeah.

Yes, I knew began or not, since I was a little young kid.

He was here. He was here. And then he went to Canada, and then he come back and he was gone for several years. Then he came back. And as an old man, he was here. When you were young.

Do people work together? That's the way that is.

Yeah, it's the big Anderson. If we're thinking about the same one. Yeah.

Why? Why did he go to Canada, I wonder why he left.

Well, I guess maybe he was going to go to Canada and take a plane back. You know where they homesteaded Canada after they homesteaded here. But he homesteaded down here on Big Bird, and then he went to Canada. And I think he took up a homestead there, too. He used to do that. You know, our brother, he did that to my second brother.

He went a homesteaded up here at Helmer. And then he here he went to Canada and took up a homestead after that.

He he was in that homestead business too. Long time.

Well, did, was big Anderson really a strong man like I've heard it said?

Well, I suppose he was an a young feller. Even the big guy.

I suppose, you know, strong man, no doubt about that. Because he was he was a big hunter, man.

I've heard he was kind of an unusual fella. I mean, he wasn't he kind of stood out as being somewhat some different from from a lot of folks.

You have. I don't know who he was. And when he was here, it was no different. Of course, they and I think if that's him, why wouldn't you wouldn't stand for I heard he took a broad action. Throw a they were invading his cabin down here and he would happen to be in it. He had a broad back there and he and it was miss them and hit the wall and struck right into the wall.

And I don't know whether or not. But that's the way they said it was. You know. But then they, you know, there's some people got these people and got them molested somewhere and they started molesting him. He didn't dig well. He wouldn't take he wouldn't have to dig. And he did dig and a half a dozen of them and jerk them out of their skin.

If he was a big guy, he was a real big man.

I've heard he was dead. He was pretty religious, too.

Brown. I think it was. I think he was a seventh day Adventist. If I'm mistaken. I think he was supposed to be a religious.

But, I don't know. He could have. He probably could be the way.

Well, did you did you notice, some, people like Phil Asplund told me that he that he had some pretty bad sore on his leg, and he had to. And he walked with a cane because it didn't.

Hit him, I think. I think he had one of them ulcers. I think it did. George. The last year he got an ulcer leg.

he didn't walk her cane, run away when I first knowing that. And he lived to be an old man. Sorry. Probably run off with a cane, I think. I think I heard it. He also, like, you know, they get. I don't know what causes that very varicose. I think so, I think it's very. Because the veins that causes that.

Did you ever hear about his his machine, his invention that he was working on?

Well, yeah, I heard about it. I didn't see him. I didn't see it, though. Yeah. Perpetual motion. He was working on that. But that didn't that didn't pan out. You're working on it though.

Where was it that he lived? Yeah. Where was his place when he came back here? That he did it.

Then down there below. Over Patterson in the mine. There. Know where Arthur Andersen lived? Yeah. Bear Creek, I don't know where you're across there.

I see Bear Creek in there. I know a little bit, but I don't know if I've been.

You know, for, Then. McKinney. Yeah, well, it's all happened by his place that crossed the river. Anderson. Place down on the creek there. You see? Mckinty own there. All right. Anderson, place. And where they cross the creek, just down below, there was no all mine. And I, I think that Big Anderson lived in that where.

They lived right inside the mine shaft. Right at the head of it. There.

Yeah. It lived that. They had his shack in the shack. That's what I heard, I don't know, I never was down there right at that. Prairie was supposed to live. That's after he come back from. Oh, that's quite a while after he came back from Canada. I guess he got so he couldn't work. He couldn't do anything. He had trouble with that one with that leg.

And he was down in there.

Oh, I'm.

Interview Index

Father came alone from Sweden at age 17. Mother and family to Michigan from Canada. Father shot after railroad trial in Michigan. Heard about Princeton area from friends. Move and taking a pre-emption claim.

How they chose Woodfell. The 1893 Depression. Traded a cow for three sacks of wheat.